I’ve spent twenty-five years writing in cafes. For a quarter of a century, I’ve attempted to produce passable fiction within the thin caffeinated air of Bay Area coffeehouses. I’ve endured countless hours of crummy music blasted overhead by baristas with something to prove—coexisted with hundreds of cafe patrons as neighbors, each with differing notions of privacy and personal space—suffered wobbly cafe tables and seats as hard as steel—and consumed gallons upon gallons of coffee, steamed soy milk, and espresso shots—all in the name of writing books someone might want to read.

My first foray into the writers’ cafe subculture came in the mid-1990s with the purchase of a Fujitsu laptop computer. This machine freed me from writing on a desktop PC-compatible occupying the corner of my bedroom. This freedom gave me a way to find a neutral place to get writing done—a place neither the home nor the office.

Cafes back then were largely for drinking coffee and reading a newspaper or book. Writing, when it was done at a cafe, was performed with pen and paper. The parallel advents of cheap personal notebooks and wireless Internet rewrote the cafe landscape in America, morphing the coffeehouse from a casual light-fare experience to a pseudo-shared office for the creative class.

Any writer will tell you, finding a good writing cafe is a cherished gift. Every change-of-address I’ve made over the last twenty-five years was always followed by long days of stumbling from one neighborhood cafe to another in search of the right one—the mother lode, Nirvana, the comfortable and welcoming writer’s cafe. Even when traveling abroad I make a point of finding a local cafe for writing.

As such, I’ve written in so many bad cafes I cannot begin to categorize them—but I’ll try.

Where to begin? There are the noisy cafes, the cafes where the baristas play Dave Matthews so loud I cannot hear my own music, even when I press my headphones tight against my ears with my palms. There are the cafes I can never find a seat in and must ask to share a table. Most creative types seem to find this burden distasteful and will invent an invisible friend joining them shortly, so, sorry, I’ll need to sit elsewhere.

There are the overpriced cafes. There are the cafes with rock-hard high stools seemingly designed by 1970s McDonald’s interior decorators. There are the cafes that are too hot, even in the winter. Here in San Francisco the opposite is largely the case, the cafes where the owner props the door wide open no matter how cold it is outside, allowing chilly breezes to charge inside at sporadic moments.

Clocking in years of cafe time taught me never to tell to anyone sniffing around me that I’m writing a novel. Doing so only elicits all manner of unproductive responses, from snarky to nosy to rude to inane. More than once I’ve had to pry myself away from a chatty cafe patron who, delighted at my endeavor, felt compelled to describe to me all their book ideas. (Sometimes they offer to let me write their book—”We’ll split the profits fifty-fifty.”) In an otherwise wonderful cafe in Campbell, a regular got his tenterhooks so deep into my work I would startle to find him crouched behind my chair peering over my shoulders to watch me write.

I’ve seen tip jars stuffed full of bills ripped from counters, the thief racing out the door with coins clanging across the floor in their wake. I’ve seen notebook computers swiped off tables while the patron was still typing and likewise rushed out the door. I’ve written in cafes decorated like giant doll houses, cafes decorated like discount clothing stores, and cafes so meticulously decorated I felt I’d entered a movie set. I’ve seen a darkened cafe in San Francisco arranged like a ziggurat with staggered levels of cafe patrons seated facing you as you enter, every one of them typing furiously on their MacBooks. The uniform rows of the backlit Apple logo could only remind me of the 1984 Super Bowl commercial.

There are cafes that cap their electrical outlets to force laptop owners to run on battery power only. There are cafes that employ exotic WiFi systems that only give you so much time online before you must buy another drink or pastry. Some cafes are too-brightly lit, making one snow-blind in the evening hours, and some cafes are so dim you cannot see your hands on the keyboard. There are the cafes that close early, eliminating prime evening-hour writing spurts, and there are the cafes that don’t open weekends for mysterious reasons.

I’ve been in cafes where the owner would assure me I could pay anytime before leaving—and then grouse I never paid for the first coffee when I return to the counter for a refill. I’ve been in cafes where the owner relentlessly pushed a food purchase on me. I’ve been in cafes with owners who grumbled under their breath about people not buying enough coffee or staying too long.

The Slate.com feature “My coffeehouse nightmare” is the Platonic example of this type of owner. He served his coffee “on silver trays with a glass of water and a little chocolate cookie,” hired a Le Bernadin baker to produce specialty croissants, and thought the fast-track to coffeehouse profits was pulling Vienna roast espresso shots instead of Italian. In six months, his cafe was out of business. “The average coffee-to-stay customer nursed his mocha (i.e., his $5 ticket) for upward of 30 minutes. Don’t get me started on people with laptops.” By which, of course, he means people like me.

Cafes hold a unique position in American culture. They straddle commercial and social divides. As a cafe patron, you are engaging in commerce with the owner and her staff. On the other hand, you share a quiet, almost intimate, personal space with other patrons, perfect strangers often seated less than a foot away. Unlike a movie theater, where all are sharing a common experience, cafes are a collection of private moments (reading a book, engaging in conversation, outlining a novel) hosted within a shared public situation. At the risk of romanticizing it, successful cafes are places where both halves—the commerce and the social—are well-balanced. Failure, I’ve always found, is where such balance is missing.

My personal code of cafe ethics? Always buy something. Don’t bring in outside food or drink. Tidy up the table before leaving. Don’t hog the electrical outlet. Voices down and phone calls outside. Please and thank you carry a lot of water in any situation, social or commercial.

What cafe do I recommend for writing? The one I’m sitting in right now. And, no, I’m not telling you its name.

And certainly Gibson can write about the Japanese as well as any Westerner I’ve read.

And certainly Gibson can write about the Japanese as well as any Westerner I’ve read.

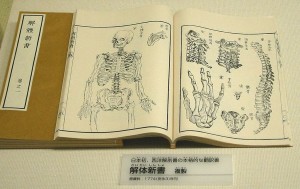

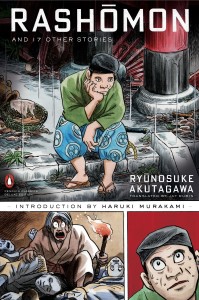

In other words, Akutagawa was accustomed to a way of life similar to the moveable feast the bohemian American ex-pats enjoyed after the First World War in Paris. It’s remarkable to me that such a writer would set modernistic and relativistic stories like “In the Grove” and “Rashomon” (and others) in feudal Japan. (Imagine Fitzgerald writing a Revolutionary War novel, or Hemingway writing a story about the Salem Witch Trials.) As a backdrop to Akutagawa’s stories, Feudal Japan appears to be constructed of the hard timber of clear-cut morality, duty, and honor—much like the mythologized Old West—and not the shaky plastic of “Rashomon”‘s moral and subjective ambiguities. Of course, perhaps that was Akutagawa’s point.

In other words, Akutagawa was accustomed to a way of life similar to the moveable feast the bohemian American ex-pats enjoyed after the First World War in Paris. It’s remarkable to me that such a writer would set modernistic and relativistic stories like “In the Grove” and “Rashomon” (and others) in feudal Japan. (Imagine Fitzgerald writing a Revolutionary War novel, or Hemingway writing a story about the Salem Witch Trials.) As a backdrop to Akutagawa’s stories, Feudal Japan appears to be constructed of the hard timber of clear-cut morality, duty, and honor—much like the mythologized Old West—and not the shaky plastic of “Rashomon”‘s moral and subjective ambiguities. Of course, perhaps that was Akutagawa’s point.