Last year I wrote about dysfunctional narratives, a type of story that Charles Baxter first identified in the 1990s and which now seems overly prevalent today. He quoted a description of them by poet Marilynne Robinson, who also identified this type of narrative. She called it a “mean little myth”:

One is born and in passage through childhood suffers some grave harm. Subsequent good fortune is meaningless because of the injury, while subsequent misfortune is highly significant as the consequence of this injury. The work of one’s life is to discover and name the harm one has suffered.

In my post, I wrote about a “Cambrian explosion” of dysfunctional narratives in our culture since the 1990s, this sense that we’re being overwhelmed by them. They’re in our magazines and books, in our cinema, in our newspapers, and on social media. “Reading begins to be understood as a form of personal therapy or political action,” Baxter wrote, and his observation seems as acute today as it did back then.

Last year I offered a few explanations for what energized this explosion. Recently I thought of another reason to add to the list. It’s a concept repeated endlessly in creative writing classes and how-to guides on writing fiction, namely, character-driven fiction versus plot-driven fiction. Respectable authors are supposed to write character-driven fiction and to eschew plot-driven fiction, which is largely associated with genre fiction.

When I first heard this edict of character versus plot, I accepted it as sage wisdom, and sought to follow it closely. Over the years, I kept hearing it from instructors and successful writers, especially writers of so-called literary fiction. I heard it so much, I began to question it. What exactly is character? What is plot?

I began to pose these questions to my peers. Their response usually sounded like this:

“‘Character’ is all the things that make a character unique. ‘Plot’ is the stuff that happens in a story.” A character-driven story is supposedly rich with humanizing details, while a plot-driven piece is a fluffy story where “a lot of stuff happens.”

Aristotle is not the final word on literary analysis, but his opinions on how a story succeeds or fails is far more nuanced than what many of my peers and instructors in creative writing programs could offer.

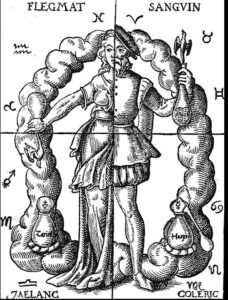

Aristotle defines character as a set of human traits imitated in the text. Traits could be run-of-the-mill personality markers, such as a character who is studious or arrogant, or complex and contradictory, like Hamlet’s brooding and questioning nature. Before modern times, playwrights often used traits associated with the four humors to define characters in a play.

For Aristotle, plot is the series of decisions a character makes that propels the story forward. These decisions generally take two forms: The character speaks, or the character acts. In line with the saying “actions speak louder than words,” Aristotle holds that a character’s actions are more significant, and more revealing, than the words they mouth.

When one of the salesmen in Glengarry Glen Ross announces he’s going close a big sale that night, and then crosses the street to have a cocktail, his actions reveal the hollowness of his words. Both decisions (speaking and acting) are also plot. Plot proves what character traits merely suggest.1

In other words, plot is not “stuff that happens.” (Note the passive voice, as though plot elements are forced upon the characters.) Rather, plot is a sequence of decisions made—and readers are very interested in a character’s decisions.

To be fair, inaction by a character is a kind of decision. Certainly there’s room for stories about characters who ponder a great deal and do little about it. In successful fiction, though, the final effect of inaction is almost always ironic. (Two good examples are Richard Ford’s “Rock Springs” and Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.”) The problem is when inaction in literary fiction is treated as sublime.

The inaccurate, watered-down definition of plot-driven fiction—”A story where a lot of stuff happens”—has led to contemporary American literature’s fascination with flabby, low-energy narratives. I’ve met authors proud that the characters in their stories don’t do anything—never get off the couch, never pick up the phone, never make a decision of any consequence. Literary fiction has come to regard passivity as a virtue and action as a vice. A writer crafting a character who takes matters into their own hands risks having their work classified as genre fiction.

For decades now, creative writing programs have been pushing an aesthetic emphasizing character traits over character decisions. It’s frustrating to watch, year after year, the primacy of character-driven fiction getting pushed on young writers, with too many of them accepting the mantra without further consideration.

And this is why I think the Cambrian explosion of dysfunctional narratives is tied to this obsession with character-driven fiction. Passivity and inactivity are keystones of Baxter’s dysfunctional narratives. In his essay, he notes the trend toward “me” stories (“the protagonists…are central characters to whom things happen”) over “I” stories (“the protagonist makes certain decisions and takes some responsibility for them”).

This is why I’m wary of character-driven writers who do not permit their protagonists to make mistakes, instead strategically devising stories where they make no mistakes, and are therefore blameless. No wonder plot—that is, decision-making—is being eschewed, when this is the kind of story being upheld and praised.

- Aristotle’s Poetics are obviously far more complicated than my three-paragraph summary, but the gist described here holds. ↩︎