Previously: An unusual parable

Next: A literary eulogy

2016 was a busy year for blogging. Amazon accepted Bridge Daughter for their Kindle Scout program, which entailed a month-long nomination process before they agreed to publish it. It was the start of a fairly intense roller coaster ride, most of which I captured in blog posts along the way.

Amazon’s imprimatur on the novel opened many doors. With a single email sent on a single day of the week to a mere sliver of their customer base, Amazon could generate hundreds of book sales, as though rubbing a lamp to summon a djinn. Amazon’s backing also led to a movie production company inquiring about film rights. They read the book and they asked questions, but ultimately they passed.

(Amazon dismantled the Kindle Scout program in 2018, which I still consider a tragedy.)

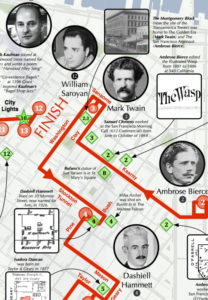

Of the long-form blog entries in 2016, I produced three that I remain proud of. I’m torn which to feature here. My account of Don Herron’s Fritz Leiber tour still evokes nostalgia. Don Herron is the creator of the classic Dashiell Hammett tour in San Francisco. Getting a chance to meet Herron and take his lesser-known Fritz Leiber tour was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, as he no longer leads it save for special occasions.

Another piece I’m proud of is my review/analysis of the Generation X cult classic Slacker, one of my favorite films. This entry has an untold side story: A few months after posting it, an online film aficionado site on Medium asked if I was interested in adapting the review. Unfortunately, what the editor wanted me to write about wasn’t what I found interesting about Slacker, and the opportunity fizzled out.

The third is a blog post I keep returning to as a kind of manifesto: “Fiction as a controlled experiment,” a write-up of my thoughts on the book On Literature by J. Hillis Miller.

Miller was a scholar at Yale and U.C. Irvine, and known for promoting deconstruction as a means of literary criticism. I discovered On Literature on a shelf of used books in a Tokyo bookstore, and assumed it would be thick with postmodern terminology and abstruse theories. Instead, On Literature is personal and ruminative. Parts of it read like a confessional. Miller admits to a lifelong love of reading, and writes in glowing terms on several children’s books he marveled over in his youth.

What caught my attention the most, however, is when he confesses to viewing a work of fiction as a “pocket or portable dreamweaver.” He describes books as devices that transport the reader to a new “hyper-world” for them to experience. The way he describes it reminds me of the linking books in the classic video game Myst.

This quaint vision of narrative is unfashionable in the world of literary criticism. Miller’s vision is also, in my view, charitable to lay readers, who are less interested in high theory and more interested in enjoying books, and curious why some books are more enjoyable than others.

But I do think this vision—”a pocket or portable dreamweaver”—is also a useful guide for an author developing a story or a novel. Miller insists a work of fiction is not “an imitation in words of some pre-existing reality but, on the contrary, it is the creation or discovery of a new, supplementary world, a metaworld.” That is what the creation of story is—not merely revealing or reporting an already existing world, but creating a new one in the author’s mind, and, in turn, recreating it in each reader’s mind. These multiple worlds are similar but never exactly the same.

Miller died in 2021 due to COVID-related issues, one month after the death of his wife of over seventy years. Reading On Literature makes me wish I could have enrolled in one of his courses. Whereas so many of the European deconstructionists seemed intent on subverting the power of literature, Miller was plainly in awe of the written word, and strove to promote it. We need more readers like him.