A guilty pleasure of mine is Planet of the Apes. I’m speaking of the original movie—not the 1970s sequels, not the remakes, not the one with the Golden Gate Bridge, and not the one everyone hates with Mark Wahlberg. I am a fan of the 1968 film that launched them all, the Charlton Heston vehicle spawning over fifty years of sequels, reboots, “re-imaginings,” TV shows, and comic books. The others have little draw for me. It’s the original I return to time and again.

The first Planet of the Apes is campy, riveting, preachy, and provocative— Franklin J. Schaffner’s sci-fi classic is the very definition of middle-brow entertainment, in that it pleases the senses while challenging the mind. The film has only grown on me over the years. I’ve come to appreciate its complexities and contradictions, even as its flaws have become more apparent as well.

Although I find it difficult to believe any person in the industrialized world today is not a little familiar with Planet of the Apes and its shocking ending, let me open by saying: Spoilers follow.

Seriously: If you’ve not watched the original 1968 film, do not continue reading. The ending is simply that stunning. I hate to think I would spoil it for anyone.

Background of the Apes

It’s sometimes said Planet of the Apes is the rare instance of the film being better than the book. I’m not so certain, although I’m convinced the film’s impact is the stronger of the two. A better description, I think, is that the novel and film are different approaches to the same source material, much as the gospels of Matthew and Luke are thought to draw upon common material from an earlier source known to scholars as Q.

The original novel—Pierre Boulle’s epistolary La Planète des singes—regards a space traveler named Ulysee who finds himself stranded on a planet circling the distant star Betelgeuse. There he discovers a modern ape civilization that enjoys all the trappings of 20th century man. The simians smoke tobacco, drive cars, shop for clothes, take walks in parks. The humans on this planet are mute, savage, and hunted for trophy. To the apes the narrator is a freak, this human who can talk and reason and claims to have fallen from the sky.

The Q Document for Boulle’s lean novel would seem to be Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, in particular Gulliver’s final voyage to the land of Houyhnhnms. Swift’s race of intelligent and speaking horses administrate an orderly and rational society on their island. Like Boulle’s apes, the Houyhnhnms are plagued by the Yahoos, mute and savage humans who rape and kill with abandon. The Houyhnhnms shocking final solution for this plague is what today we would call genocide: Their Assembly votes to exterminate the Yahoos. The apes on Boulle’s planet seem to be building toward a similar resolution.

In Bright Eyes, Ape City: Examining the Planet of the Apes Mythos, a recent critical examination of all things Ape, contributor Stephen R. Bissette reveals a number of antecedents to Boulle’s slim novel of apes running a world. In particular, he focuses on the popular 1904 French short story “Le Gorilloide et Autres Contes de L’Avenir.” This story and its author, Edmond Haraucourt, were so popular in the first half of the 20th century, Bissette notes “it is impossible to read ‘Le Gorilloide’ for the first time and not be rocked by the realization that Pierre Boulle had to have read this story, or at least heard of it. … This is the Holy Grail for Apes devotees.” Furthermore, Bissette catalogs an entire corpus of ape-world stories predating Boulle’s novel, from science-fiction shorts to comic books.

These earlier ape-world stories would seem to dilute the originality of Boulle’s novel. From Bissette’s capsule summaries, none of these earlier authors seemed to have the same ambition as Boulle, making La Planète des singes a kind of sui generis in the intersection of science fiction and “social fantasy,” as Boulle himself called it.

While I can’t offer any direct literary evidence Boulle was working out of Swift’s mode of satire, it seems rather obvious he was. The other stories cataloged by Bissette make much of apes running a planet; Boulle made much about a man being treated as an animal because he is an animal, which corresponds neatly with Swift’s dark worldview.

Like Gulliver, Boulle’s protagonist Ulysee is a wide-eyed narrator brimming with wonder and curiosity. The common device of animals with human-like qualities allows Swift and Boulle to hold a polished mirror up to man’s violence, avarice, and ignorance, to interrogate our supposed civilized rise over the beasts, and to show our vices for what they are. Ulysee and Gulliver adapt to the animals’ ways, even going so far as to adopt their language, culture, and mannerisms. Both animal societies are generally better-run than man’s, although Boulle and Swift are smart enough to give their respective animal races blind spots. For Boulle’s apes, it’s unquestioned faith; for Swift’s horses, excessive pride.

“I shot an arrow into the air”

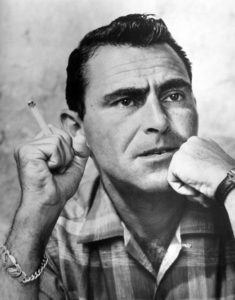

Shortly after publication of Boulle’s novel, Rod Serling of Twilight Zone fame was tapped to write a big-screen adaptation. Serling kept the device of an astronaut landing on a planet run by apes—how could he not?—as well as Ulysee’s crueler treatment at the hands of the apes. He also carried forward the main ape characters, scientists Zira and Cornelius, and Dr. Zaius, the authoritarian keeper of ape law. Beyond that, Serling jettisoned most of Boulle’s novel in favor of a darker, more cynical territory.

Because the movie’s credits list Michael Wilson before Serling, there was a long-running question of how much of the movie emerged from the Twlight Zone creator’s pen. Wilson’s silver screen credits include such monuments as Lawrence of Arabia, Boulle’s The Bridge on the River Kwai, and A Place in the Sun. Some wondered if Serling’s contributions had been overplayed compared to this seasoned Hollywood writer.

A 1998 issue of Creative Screenwriter settled the question by examining Serling’s early scripts. They show Serling definitely shaped the novel into what the movie finally resembled, including his idea for the stunning final moment, one of the most shocking endings in Hollywood history.

Serling also carried forward Boulle’s concept of apes living in a modern world much like our own, which was abandoned before production began. The final movie’s apes inhabit mud huts on the edge of a desert. They make do with horseback travel and wooden carts and dirt roads. This change was apparently due to studio budget restrictions, and Michael Wilson’s revisions accorded this limitation. Wilson or another writer (probably John T. Kelley) also “punched up” Serling’s dialogue, yielding several groan-inducing aphorisms (“I never met an ape I didn’t like”, “human see, human do”). Later drafts also introduced the teenage ape Lucius, who preposterously carpet-bombs the last act of the film with anachronistic counterculture lingo. Leaving these “improvements” on the cutting room floor would have done much to polish the final film.

Still, the artistic compromise of a pre-industrial ape society fortuitously contributed to, rather than detracted from, Serling’s vision. In the film, the apes maintain an austere, Puritanical social structure. They live close to the field, close to the well, and close to their scripture. Zira’s and Cornelius’ claim of discovering a man who can talk doesn’t merely fly in the face of scientific thinking (as in Boulle’s novel), but against religious orthodoxy, adding an Inherit the Wind subtext that supercharges the movie’s stakes.

As with the original novel, Gulliver’s Travels seems to be a source for the film, and not merely the device of man trapped in an animal society. Swift’s misanthropy is far stronger in Serling’s vision than Boulle’s. When the Houyhynms vote to destroy the Yahoos, it’s not a stretch to think Swift is advocating for the destruction of the actual human race. This level of misanthropy is nowhere to be found in Boulle’s work; Serling’s script is marinated in it. Serling’s nicotine-addled gaze and his penchant for purple dialogue means the script affords more time for damning philosophizing than in Boulle’s work.

The vehicle for Serling’s misanthropy is Taylor (Charlton Heston), a red-blooded, cigar-chomping astronaut who replaces Boulle’s wide-eyed French explorer. Unlike Ulysee and Gulliver, Taylor never lowers himself to the ape’s level—or, perhaps, he never rises to their stature. Considering the European backgrounds of Swift and Boulle, perhaps Serling’s choice of a hardheaded “cowboy” astronaut is indicative of Serling’s American-ness. Or, perhaps Serling was making a statement about the hubris of his countrymen. America was deep in the Vietnam War by this point. American exceptionalism was being questioned from all sides.

“I leave the 20th century with no regrets”

Although some critics knock the movie as pretentious action-adventure fare, the film’s sensitive opening doesn’t line up with such dismissive claims. Staring out a spaceship’s viewport at an expanse of stars, astronaut Taylor notes that, due to Einsteinian relativity, hundreds of years have passed on Earth although the crew has only been traveling for six months of ship time. Speaking into a black box recorder, the cynical Taylor announces “I leave the 20th century with no regrets.”

Then he admits

“Seen from out here, everything seems different. Time bends. Space is boundless. It squashes a man’s ego. I feel lonely.”

Before slipping into extended stasis for the final leg of their journey, Taylor offers the listener of his voice recorder—whomever it may be—his final thoughts:

“Does man, that marvel of the universe, that glorious paradox that sent me to the stars, still make war against his brother? Keep his neighbor’s children starving?”

Serling’s script opens not with high action or tense drama. It doesn’t even open with the inciting incident, a bang to set the story into motion. Taylor’s admission before falling into hypersleep sounds like a confession from a man not in the habit of making confessions.

After the opening credits, the crew awakens to discover they’ve crash-landed on a desolate planet. Taylor’s vigorous misanthropy immediately fills the screen. He taunts the others for holding any faith in the survival of America or even civilization. He declares mankind all-but-extinct, and with the only female crew member dead, its destruction now seems assured. He boasts how satisfied he is to leave Earth behind, and wonders if the remaining crew will last a week on this daunting new planet.

It’s Taylor’s private admission to the black box—”It squashes a man’s ego. I feel lonely”—that reveals his confident cynicism is to some degree a facade. Not coincidentally, packed inside those two sentences is a concise foreshadowing of the film’s conclusion.

“I’ve always feared man”

Taylor, one of the last examples of “that marvel of the universe, that glorious paradox,” is hunted and captured by the apes. He’s subjected daily to humiliations fit for a laboratory animal: Stored in a cage, rewarded with food, washed down from a hose (a movie visual sickeningly similar to a strategy police used in the 1960s on peaceful civil rights protestors), and given a mate to encourage breeding. The threat of castration and lobotomization looms in the background (the latter a trendy topic in a decade preoccupied with the treatment of mental illness).

Charlton Heston turns in a rather physical performance as he’s stripped naked, manacled, chained, gagged, and paraded through streets on a leash. Due to a throat injury Taylor literally has no voice against his captors. When he regains his voice—the campy “Take your stinkin’ paws off me, you damn dirty ape!”—he discovers he still has no say in this society of apes, where he’s regarded as an ignorant freak of nature.

Taylor’s hatred of man isn’t challenged by the apes or ape society, it’s reinforced. As with the lands Gulliver travels to, evidence of man’s failings abound on this supposedly backwards planet. The apes don’t kill each other. They seem to have no war or famine or deprivation to speak of. While not perfect, they seem to have built a more egalitarian society than the world Taylor left behind. And yet Taylor can’t help but see himself as their equal. Soon his human ego leads him to believe he’s their superior. This shift is so subtle and smooth the viewer doesn’t even sense it.

Serling is a cruel god to his creation. It’s not ironic enough for misanthropic Taylor to entertain notions of equality with the apes. Serling forces Taylor to defend mankind as intelligent and rational while standing naked and unwashed before a tribunal of jeering, dismissive apes. When Taylor visits an archeological dig and proves man ruled the planet before the apes, his defense seems all the more credible. Headstrong Taylor makes much hay over his victory.

Consider the film’s opening once more. In his voice recorder, Taylor’s questions—”Does man still make war on his brother? Keep his neighbor’s children starving?”—are obviously not questions at all. Taylor believes man is incapable of changing his basic nature. After crash-landing on the ape planet, Taylor mocks the notion mankind might have survived the five thousand-year span. His attitude is one of good riddance: “I leave the 20th century with no regrets.” Yet by the third act, this man is sneering down on the apes and declaring man was better, stronger, and most importantly, first.

With Taylor’s hubris reaching a crescendo, he twists out this admission from Dr. Zaius:

“I’ve always feared man. From the evidence, his wisdom must have walked hand-in-hand with his idiocy. His emotions must rule his brain. He must be a warlike creature who gives battle to everything around him. Even himself.”

At this point, Taylor has won. He’s gained his freedom as well as an admission of man’s primacy from the ape’s top authority. If the movie ended with Taylor riding his horse into the horizon, perfectly free, it would have been a tidy, if unsatisfying, ending.

Discovering the Statue of Liberty is the door slamming shut on Taylor. Cowering on the beach naked as Adam, he realizes

“I’m back. I’m home. All the time it was—”

Taylor’s character arc is one of the cruelest, most severe punishments I’ve ever seen in film or literature. Gulliver leaves the island of the horse Houyhnhnms unable to stand the sight or smell of other humans, but his change is orders of magnitude less than Taylor’s crushing defeat at the foot of the Statue of Liberty. Taylor’s misanthropy has been scooped out of his black heart and fed back to him in a dog’s bowl.

In the first act, one of the surviving astronauts attempts to plant a tiny American flag in the dirt of their newly-discovered planet. Taylor roars in laughter at the absurd futility. In the final scene, another American symbol in ruins towers over him, with Taylor on the beach like a meager, limp flag planted in the sand. He’s the object of amusement now, and his climb from misanthropist to philanthropist has collapsed and crushed him whole.

(Update: The events related in this blog post led to me writing

(Update: The events related in this blog post led to me writing

The cadences and rhythms of Doyle’s stories almost appear crafted for train reading. The percussion of the shinkansen tracks below and the low whistle of the passing wind was the perfect white noise to accompany a Holmes mystery. More than once I started a story as our train left the station, and by the time Holmes was announcing his solution, we were slowing for our next stop. Obviously Doyle wasn’t timing his stories for bullet trains, but it felt he crafted them with a sense of being read in a single sitting between destinations, whether traveling by steam or horse or electromagnets.

The cadences and rhythms of Doyle’s stories almost appear crafted for train reading. The percussion of the shinkansen tracks below and the low whistle of the passing wind was the perfect white noise to accompany a Holmes mystery. More than once I started a story as our train left the station, and by the time Holmes was announcing his solution, we were slowing for our next stop. Obviously Doyle wasn’t timing his stories for bullet trains, but it felt he crafted them with a sense of being read in a single sitting between destinations, whether traveling by steam or horse or electromagnets. By the time I returned from Japan, I’d devoured three Sherlock Holmes collections. For all the faults and stuffiness, Doyle is a generous writer, one who engaged with his readership and even challenged them a bit, but never denying them their desires. I suspect Doyle (like Dickens) read correspondence from his readers and was sensitive to their criticisms and praise. I don’t think it’s an accident Doyle modeled his first-person narrator as a physician, Doyle’s own intended profession, or that Watson wrote of Holmes’ exploits under the conceit of penning newspaper articles. Not only did it fill the public with the sensation Holmes was alive—many believed so at the time—but Watson’s audience also gave Doyle the house for which to apply the paint.

By the time I returned from Japan, I’d devoured three Sherlock Holmes collections. For all the faults and stuffiness, Doyle is a generous writer, one who engaged with his readership and even challenged them a bit, but never denying them their desires. I suspect Doyle (like Dickens) read correspondence from his readers and was sensitive to their criticisms and praise. I don’t think it’s an accident Doyle modeled his first-person narrator as a physician, Doyle’s own intended profession, or that Watson wrote of Holmes’ exploits under the conceit of penning newspaper articles. Not only did it fill the public with the sensation Holmes was alive—many believed so at the time—but Watson’s audience also gave Doyle the house for which to apply the paint.