(Update: The events related in this blog post led to me writing A Man Named Baskerville, now available in Kindle and paperback.)

(Update: The events related in this blog post led to me writing A Man Named Baskerville, now available in Kindle and paperback.)

Last summer I had the great fortune to spend ten weeks in Japan. I traveled by train up and down the islands, from the agriculturally diverse Hokkaido to the richly historical city of Nagasaki at the southern tip of Kyushu. Japan is a fugue of culture, architecture, and landscape. The country never repeats itself, but is stitched together by interlocking themes.

On one leg of the trip I made the key mistake of failing to pack a second book, thinking B. Traven‘s The Death Ship was a hefty enough read until my return to Tokyo. Well, I ripped through The Death Ship in no time (a great novel, by the way) and found myself facing a long stretch of time on Japan’s shinkansen (bullet train) without a thing to read. Even if I understood Japanese, Japan’s trains are not like other systems where you might chance on a discarded newspaper or a light magazine in the seat-back pocket. The Japanese do not leave their detritus behind when they detrain. They even pick up their trash when they exit a baseball game.

Desperate, I searched my smartphone and discovered on my Kindle app The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1892), the first published collection of Holmes’ adventures. Most of the collection’s story titles are as well-known as books of the Bible: “The Adventure of the Red-headed League”, “A Scandal in Bohemia”, “The Adventure of the Speckled Band”, and more. The stories have fallen into the public domain, hence the collection is often the free sample book Amazon supplies when you buy a Kindle or install their app.

Before my trip to Japan, I was never a fan of Sherlock Holmes. I found the Victorian airs and British pleasantries stuffy compared to Holmes’ American counterparts. When I first read “The Adventure of the Dancing Men” at age ten or eleven, I was going through a boyhood codes-and-ciphers phase. By all rights I should have loved the story. Instead I felt a bit let down by its lack of focus on actual cryptanalysis. As I learned on that train ride, Doyle’s stories are often more concerned with a viscount’s ancestry or Tsarist intrigue or preserving the good name of the British Empire than the dead body lying at Holmes’ and Watson’s feet.

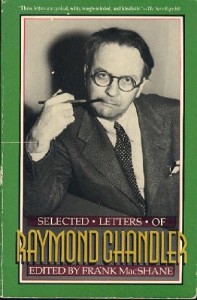

All this is to explain that although I’ve read mystery fiction my entire life, from Encyclopedia Brown at the age of seven to the adult pleasures of Chandler’s The Long Goodbye (which I reread every few years), on that bullet train ride I was not terribly conversant with the Sherlock Holmes corpus. I’d read The Hound of the Baskervilles a few years before at an acquaintance’s suggestion when I mentioned I’d enjoyed the neo-Gothic Rebecca. Other than some Sherlock Holmes movie spoofs and casual viewing of Jeremy Brett’s BBC series, my exposure to the detective was largely through cultural references and the turns of phrase that have entered our common language, much like someone ignorant in Shakespeare will recognize bits of Hamlet.

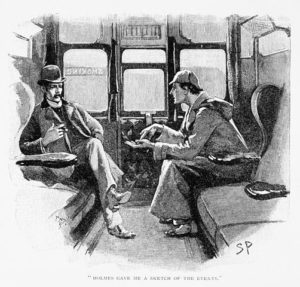

Something wonderful happened on that train ride from Tokyo to Kyoto. As these stories of detection and deduction spooled out before me, I realized much of Doyle’s contemporary British audience would have been reading these stories on trains as well. Since he was writing for Strand magazine, Doyle’s audience would’ve picked up a copy at a newsstand before boarding, the Victorian version of buying a thriller at an airport bookstore before a long plane ride.

The cadences and rhythms of Doyle’s stories almost appear crafted for train reading. The percussion of the shinkansen tracks below and the low whistle of the passing wind was the perfect white noise to accompany a Holmes mystery. More than once I started a story as our train left the station, and by the time Holmes was announcing his solution, we were slowing for our next stop. Obviously Doyle wasn’t timing his stories for bullet trains, but it felt he crafted them with a sense of being read in a single sitting between destinations, whether traveling by steam or horse or electromagnets.

The cadences and rhythms of Doyle’s stories almost appear crafted for train reading. The percussion of the shinkansen tracks below and the low whistle of the passing wind was the perfect white noise to accompany a Holmes mystery. More than once I started a story as our train left the station, and by the time Holmes was announcing his solution, we were slowing for our next stop. Obviously Doyle wasn’t timing his stories for bullet trains, but it felt he crafted them with a sense of being read in a single sitting between destinations, whether traveling by steam or horse or electromagnets.

How often does Holmes send Watson scurrying to locate a train schedule to confirm some paramount clue or destroy an alibi? How often does Holmes engage in mysterious research in London before setting off by train first thing in the morning, only revealing the details of his research to Watson on the ride north?

Holmes and Watson call for cabs, hire carriages and watercraft, borrow steeds, follow bicycle tracks, and so on. Freedom of mobility is vital to a Sherlock Holmes story. It’s the core question in “The Adventure of the Solitary Cyclist” and “The Adventure of the Copper Beeches”. A horse-and-carriage ride is the central puzzle in “The Adventure of the Engineer’s Thumb”. The climax of A Study in Scarlet involves, of all things, hailing a cab off Baker Street.

![]()

All fiction writers are writing to a perceived readership, whether they acknowledge it or not. This is distinct from a “target audience,” which commercial writers are all too familiar with. (A staff writer for Wired magazine will consciously know her target audience, which is distinct from the target audience for a sportswriter in a Midwestern farming community.) My notion of a “perceived readership” is more personal than a target audience, a writer’s internalization of their desired audience rather than a market demographic.

Some writers write with magazine editors and agents and publishers in mind—people they hope will publish the story they’re crafting. Some writers think of authors they admire or authors they desire to emulate. Some writers are thinking of friends and family whom they hope to impress, or at least earn their respect. Some writers are thinking of the public at large (whatever that abstract concept means) hoping to earn a wide audience.

Unlike “target audience,” it doesn’t mean the writer is actually writing for this perceived reader. The writer doesn’t actually believe only their friends will read their book, or that some big-name writer will pick it up, especially since that big-name writer may be dead. But just as painting a house requires a house to apply the emulsion, a perceived readership in the back of a writer’s mind gives the writer a kind of fuzzy target to aim for without committing to it.

By the time I returned from Japan, I’d devoured three Sherlock Holmes collections. For all the faults and stuffiness, Doyle is a generous writer, one who engaged with his readership and even challenged them a bit, but never denying them their desires. I suspect Doyle (like Dickens) read correspondence from his readers and was sensitive to their criticisms and praise. I don’t think it’s an accident Doyle modeled his first-person narrator as a physician, Doyle’s own intended profession, or that Watson wrote of Holmes’ exploits under the conceit of penning newspaper articles. Not only did it fill the public with the sensation Holmes was alive—many believed so at the time—but Watson’s audience also gave Doyle the house for which to apply the paint.

By the time I returned from Japan, I’d devoured three Sherlock Holmes collections. For all the faults and stuffiness, Doyle is a generous writer, one who engaged with his readership and even challenged them a bit, but never denying them their desires. I suspect Doyle (like Dickens) read correspondence from his readers and was sensitive to their criticisms and praise. I don’t think it’s an accident Doyle modeled his first-person narrator as a physician, Doyle’s own intended profession, or that Watson wrote of Holmes’ exploits under the conceit of penning newspaper articles. Not only did it fill the public with the sensation Holmes was alive—many believed so at the time—but Watson’s audience also gave Doyle the house for which to apply the paint.

Doyle’s perceived readership began to coalesce with his target audience, like blurry double-vision sharpening into a single distinct form. I’m not arguing this is desirable or advantageous, but I do think it happened and that Doyle’s writing was the better for it. I also believe this is part of the reason for Sherlock Holmes’ character persisting as a vivid creative construct well into the 21st century. After all, Holmes’ as an individual is not some empty vessel for each generation of readers to pour their own ideals into. His persistence comes from being odd, unique, idiosyncratic, and ripe for reinterpretation.

This connection between author and perceived readership is a direct rebuttal to the 20th century myth of the “walled-off” author, the lone genius in a room with a typewriter penning works of high art unsullied by mammon or mass culture. While Nabokov, Faulkner, and Woolf may not have been writing for money and celebrity—although I think people are too quick to assume such things—I certainly believe all three were writing for a perceived readership, some idealized notion of the reader they wished to attract.

With the rise of ride-sharing like Uber and Lyft, and with the inevitable arrival of driverless cars in the future, we may experience a fresh resurgence of people with additional time on their hands to read. Who knows? Much as digital music led to the renewal of singles, there may soon be a burgeoning market for short stories and story collections, mysteries and otherwise, as people seek a brief form of entertainment while traveling.

What kind of story matches the cadences and rhythms of a self-driving car? And can America today produce writers as sensitive and generous as Doyle?

Recently I picked up Robert Silverberg’s superb Science Fiction 101: Exploring the Craft of Science Fiction, an unfortunate title for a remarkably sturdy book. Part memoir, part writing guide, part anthology, I’d recommend it to every writer whether or not they’re interested in science fiction as a genre or pursuit.

Recently I picked up Robert Silverberg’s superb Science Fiction 101: Exploring the Craft of Science Fiction, an unfortunate title for a remarkably sturdy book. Part memoir, part writing guide, part anthology, I’d recommend it to every writer whether or not they’re interested in science fiction as a genre or pursuit. Science Fiction 101 also reprints thirteen classic science fiction stories from authors like Damon Knight, Philip K. Dick, Robert Scheckly, Vance, Pohl, Aldiss…the table of contents reads like the short list of first-round inductees to The Science Fiction & Fantasy Hall of Fame. Alongside each story, Silverberg comments on why it impressed him and what he gleaned, offering hard, complete examples to his writing wisdom that so many other guides lack.

Science Fiction 101 also reprints thirteen classic science fiction stories from authors like Damon Knight, Philip K. Dick, Robert Scheckly, Vance, Pohl, Aldiss…the table of contents reads like the short list of first-round inductees to The Science Fiction & Fantasy Hall of Fame. Alongside each story, Silverberg comments on why it impressed him and what he gleaned, offering hard, complete examples to his writing wisdom that so many other guides lack. Silverberg’s candor and generosity to the reader is so no-nonsense, he even reprints the rejection notes he received while canvassing science fiction magazines with his early work. Big-name writers usually dip into their rejection stack for the wrong reasons: to settle a score, or thumb their nose at those who stood in their way years past. Here, Silverberg reprints rejection slips that served to make him a better writer, admitting how he deserved them, and how he was often too young to take their advice at face-value.

Silverberg’s candor and generosity to the reader is so no-nonsense, he even reprints the rejection notes he received while canvassing science fiction magazines with his early work. Big-name writers usually dip into their rejection stack for the wrong reasons: to settle a score, or thumb their nose at those who stood in their way years past. Here, Silverberg reprints rejection slips that served to make him a better writer, admitting how he deserved them, and how he was often too young to take their advice at face-value.

Not too long ago I finished reading J. Hillis Miller’s On Literature, a slim and thoughtful consideration of the role of the written word at the end of the 20th century. Born from a lecture at UC Irvine in 2001, Miller expanded his talk into six chapters and 160 pages of conversational prose asking the simple but still-unanswered questions of literary theory: What is literature? Why read it? And how does it “work”?

Not too long ago I finished reading J. Hillis Miller’s On Literature, a slim and thoughtful consideration of the role of the written word at the end of the 20th century. Born from a lecture at UC Irvine in 2001, Miller expanded his talk into six chapters and 160 pages of conversational prose asking the simple but still-unanswered questions of literary theory: What is literature? Why read it? And how does it “work”?

The problem with describing fiction as a hyper-reality or virtual world is that these terms suggest science fiction. When I was young, one of my favorites books was Joe Haldeman’s science-fiction story collection Dealing in Futures. Its title instantly suggests that the book will generate for you any number of alternate worlds of a future time—that it’s “a pocket or portable dreamweaver.” Miller doesn’t limit this idea to science fiction, however. He sees all fiction as generators of virtual worlds.

The problem with describing fiction as a hyper-reality or virtual world is that these terms suggest science fiction. When I was young, one of my favorites books was Joe Haldeman’s science-fiction story collection Dealing in Futures. Its title instantly suggests that the book will generate for you any number of alternate worlds of a future time—that it’s “a pocket or portable dreamweaver.” Miller doesn’t limit this idea to science fiction, however. He sees all fiction as generators of virtual worlds.