In The Breakfast Club, introverted Allison dares rich-girl Claire to say if she’s a virgin. When Claire demurs, Allison says,

It’s kind of a double-edged sword isn’t it? … If you say you haven’t [had sex], you’re a prude. If you say you have, you’re a slut. It’s a trap.

This is how I feel when the question comes up about the distinction between literary and genre fiction. If you write literary novels, you’re a prude. If you write genre books, you’re a slut.

Is it really that simple? Nothing in this world is so simple. Yet, here are some true-life examples from my own experiences:

Prude

While shopping around my first novel, I got a tip that a prestigious national imprint had a new editor seeking fresh manuscripts. I sent mine along, hopeful but also realistic about my chances.

The rejection slip I received was fairly scathing. The editor claimed my book read of a desperate MFA student who doesn’t understand the “real world.” It was fairly derogatory (and oddly personal, considering this editor and I shared a mutual friend). A simple “thanks, no thanks” would have sufficed, but this editor decided it was my turn in the barrel.

Make no mistake: This hoity-toit imprint reeks of MFA aftershave. It’s not a punk-lit imprint. It’s not an edgy alt-lit imprint. It publishes high-minded literary fiction. The author list is upper-middle- to upper-class, blindingly white, and yes, many of them hold an MFA.

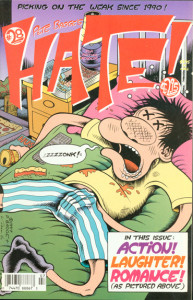

And I hold an MFA too, so perhaps the criticism is spot-on—except I wrote the bulk of novel before I set foot in grad school. I didn’t aim for it to be a literary masterpiece. I wanted to write a page-turner. It’s categorized as literary fiction because it’s not mystery, science-fiction, fantasy, romance, Western, thriller, or YA/New Adult. Write a story about a character and his family, and it’s not merely literary, you’re trying to “be literary.” Who knew?

In my novel, the main character has grown up in a town of physicists who design and perfect weapons of mass destruction—this is the actual childhood I experienced. I thought it would be a good read. (It is a good read.) My character is snarky, sarcastic, crude—and at times, he can be a right asshole. The technical background of the novel is, as they say, ripped from the headlines.

This seems pretty real-world to me. I thought I was writing a funny novel with an unusual setting and situation. This editor took it upon herself to declare I’m actually a Raymond Carver-esque hack penning quiet stories of bourgeois desperation. And that I should stop being that writer.

So, there’s the rejection slip telling me to quit being literary, even though that’s a categorization I never asked for. And it came from a literary publishing house. It’s kind of a double-edged sword, isn’t it?

Slut

After Amazon published my second novel, I began to sense a change in the attitudes of many of my writer friends. At first it was slight, like a shift in air movement when a door in the room is opened. Gradually, though, the emotional tension grew to the point it could not be denied.

I wondered if the problem was one of jealousy. My book had been picked up by a large company, but Amazon was not what you would call an A-list publisher (back then, at least—times have changed). And, they only published my book in digital Kindle format. I had to rely on CreateSpace to offer a paperback edition. The advance money was not huge, and the publicity not so widespread. It all seemed pretty modest to me, and I thought my friends would recognize it as such.

My novel is set in an alternate universe where human reproductive biology is tweaked in a rather significant way. This book is obviously science-fiction. Since the protagonist is a thirteen-year-old girl, it neatly fits into the YA slot as well.

And I’m comfortable with those categorizations. I grew up reading Asimov, Bradbury, Silverberg, and other science-fiction writers of the Golden and Silver Ages who laid so much groundwork for the genre. More importantly, I wanted to write another page-turner, a real unputdownable book. From the Amazon reviews, I think I succeeded.

The tip-off for the issue with my friends was when my wife asked one of them if she’d read my new book. The answer was a murmured, “I would never read a book like that.” This from a person I counted as a friend, and had known for ten years.

Before this, I’d heard her repeat the trope that all genre fiction is formula, as mindless as baking a cake from a box of mix. I always let it go, for the sake of harmony. Now it was being thrown in my face.

The funny thing is, one Amazon editor told me she felt in hindsight my science-fiction YA novel was not a good fit for their imprint. They were more interested in “accessible” genre fiction for their readers, and that my work was—yep—too literary. It’s a trap.

Tease

When Claire refuses to reveal if she’s a virgin, bad-boy Bender suspects she’s a tease:

Sex is your weapon. You said it yourself. You use it to get respect.

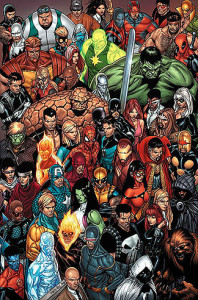

Between being a literary author and a genre writer, there’s a third way: The literary-genre writer. These are the teases. They write genre fiction, but make it literary to get respect. And, often they do.

Examples of teases are Haruki Murakami, China Miéville, Cormac McCarthy, and Margaret Atwood. Much of their work is patently genre, but they are received and analyzed with the same awe and respect reserved for literary novelists.

The knee-jerk reaction is to say these writers prove it’s possible to write literary-genre fiction. I don’t think that’s true at all, though. It only proves that authors accepted into the literary realm get to have it both ways: They avoid the stigma of genre fiction while incorporating the high-stake dramatic possibilities genre fiction offers.

Consider another literary-genre writer: Kurt Vonnegut. He wrote science-fiction, but his books are rarely shelved in that section. Hell, he even wrote a diatribe about how bad science-fiction writing is (Eliot Rosewater’s drunken “science-fiction writers couldn’t write for sour apples” screed). Yet, Vonnegut is rarely, if ever, permitted into the same circle as Atwood or McCarthy. There’s something “common” about Vonnegut. Only at the end of his life was he cautiously allowed into the literary world. Some still say he doesn’t belong there.

I remain unconvinced it’s the sophistication of a novel itself that moves it into the upper literary tiers. I can point to plenty of books supposedly in the literary strata that are not exceedingly well-written or insightful. Something other than an airy quality is the deciding factor.

The success of a handful of literary-genre writers doesn’t open doors, it only creates a new double-edged trap. An author who pens a literary-style novel can claim it’s literary. See, he added his book to the “Literary Fiction” section on Amazon! But does it mean he’s a member of the literary world? Not at all. There’s something else holding him back.

The trap

The literary/genre distinction purports to explain every aspect of a story: Its relevance, its significance, its quality, its audience, even the goals of the writer when they sat down to write it. Nothing in this world is so simple.

There’s a smell about the literary/genre divide. It smells like class. Literary is upper-class, and pulpy genre is for the proletariat. This roughly corresponds to the highbrow/lowbrow classifications. We even have a gradation for the striving petty bourgeoisie, middlebrow.

(Even calling a novel “middlebrow” is treated with disdain—a lowbrow attempt to raise a genre book to a higher status. It’s easy to fall down the literary/genre ladder, but difficult to ascend.)

I definitely believe the Marxist notion of class exists, both abroad and here in the United States. What I don’t believe is that a work of fiction is “of a class.” Books are utilized as a marker of class—tools to express one’s status. Distinctions like literary vs. genre communicate to members of each class which books they should be utilizing…I mean, reading.

This is not the most original thought, but is it really that simple? Nothing in this world is so simple. And I don’t want it to be simple. As with food, the best reading diet is varied, eclectic, and personal.

Note the real damage here. If a writer writes the books he or she wants to write, and puts their heart and soul into making it the highest-quality they can for their readers, all that hard work is instantly deflated by the literary/genre prude/slut highbrow/lowbrow labels.

And if a writer introduces genre conventions into their literary work, they’re a sell-out—a prude tarting it up for cheap attention. And if the author of a genre novel tries to achieve a kind of elegance with their prose and style, they’re overreaching—a slut putting on a church dress. You use it to get respect. We’re punishing people for being ambitious.

I’ve said it elsewhere: People will judge a book by its cover, its publisher, the author’s name, the number of pages, the title, the price, the infernal literary/genre label, its reviews, the number of stars on Amazon—everything but the words between the covers. You know, the stuff that matters.

(Update: The events related in this blog post led to me writing

(Update: The events related in this blog post led to me writing

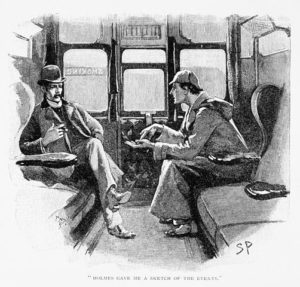

The cadences and rhythms of Doyle’s stories almost appear crafted for train reading. The percussion of the shinkansen tracks below and the low whistle of the passing wind was the perfect white noise to accompany a Holmes mystery. More than once I started a story as our train left the station, and by the time Holmes was announcing his solution, we were slowing for our next stop. Obviously Doyle wasn’t timing his stories for bullet trains, but it felt he crafted them with a sense of being read in a single sitting between destinations, whether traveling by steam or horse or electromagnets.

The cadences and rhythms of Doyle’s stories almost appear crafted for train reading. The percussion of the shinkansen tracks below and the low whistle of the passing wind was the perfect white noise to accompany a Holmes mystery. More than once I started a story as our train left the station, and by the time Holmes was announcing his solution, we were slowing for our next stop. Obviously Doyle wasn’t timing his stories for bullet trains, but it felt he crafted them with a sense of being read in a single sitting between destinations, whether traveling by steam or horse or electromagnets. By the time I returned from Japan, I’d devoured three Sherlock Holmes collections. For all the faults and stuffiness, Doyle is a generous writer, one who engaged with his readership and even challenged them a bit, but never denying them their desires. I suspect Doyle (like Dickens) read correspondence from his readers and was sensitive to their criticisms and praise. I don’t think it’s an accident Doyle modeled his first-person narrator as a physician, Doyle’s own intended profession, or that Watson wrote of Holmes’ exploits under the conceit of penning newspaper articles. Not only did it fill the public with the sensation Holmes was alive—many believed so at the time—but Watson’s audience also gave Doyle the house for which to apply the paint.

By the time I returned from Japan, I’d devoured three Sherlock Holmes collections. For all the faults and stuffiness, Doyle is a generous writer, one who engaged with his readership and even challenged them a bit, but never denying them their desires. I suspect Doyle (like Dickens) read correspondence from his readers and was sensitive to their criticisms and praise. I don’t think it’s an accident Doyle modeled his first-person narrator as a physician, Doyle’s own intended profession, or that Watson wrote of Holmes’ exploits under the conceit of penning newspaper articles. Not only did it fill the public with the sensation Holmes was alive—many believed so at the time—but Watson’s audience also gave Doyle the house for which to apply the paint.