Recently I picked up Robert Silverberg’s superb Science Fiction 101: Exploring the Craft of Science Fiction, an unfortunate title for a remarkably sturdy book. Part memoir, part writing guide, part anthology, I’d recommend it to every writer whether or not they’re interested in science fiction as a genre or pursuit.

Recently I picked up Robert Silverberg’s superb Science Fiction 101: Exploring the Craft of Science Fiction, an unfortunate title for a remarkably sturdy book. Part memoir, part writing guide, part anthology, I’d recommend it to every writer whether or not they’re interested in science fiction as a genre or pursuit.

Silverberg mingles his breezy autobiography of struggling to get published as a young man in the 1950s with nuggets of practical writing advice he picked up along the way. All of this package is humbly offered to the reader. Even when penning the book in 1987, Silverberg remains in awe of Asimov, Bradbury, and Heinlein (“our Great Exception in almost everything”), although by that time Silverberg’s name was mentioned in the same breath as those masters, and more.

Science Fiction 101 also reprints thirteen classic science fiction stories from authors like Damon Knight, Philip K. Dick, Robert Scheckly, Vance, Pohl, Aldiss…the table of contents reads like the short list of first-round inductees to The Science Fiction & Fantasy Hall of Fame. Alongside each story, Silverberg comments on why it impressed him and what he gleaned, offering hard, complete examples to his writing wisdom that so many other guides lack.

Science Fiction 101 also reprints thirteen classic science fiction stories from authors like Damon Knight, Philip K. Dick, Robert Scheckly, Vance, Pohl, Aldiss…the table of contents reads like the short list of first-round inductees to The Science Fiction & Fantasy Hall of Fame. Alongside each story, Silverberg comments on why it impressed him and what he gleaned, offering hard, complete examples to his writing wisdom that so many other guides lack.

It’s fair to compare Science Fiction 101 to Stephen King’s On Writing. Both books are a bit more practical and pragmatic in their advice than loftier musings on the craft, such as John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction. I suspect Gardner would peer down his nose at writing advice from Silverberg or King, which is too bad. Anyone who can forge a lifetime career with pen in hand deserves to be listened to and considered.

As a young man, while sweating over a typewriter struggling to earn publication credits in the science fiction magazines of yore, Silverberg also earned a degree in English Literature at Columbia University. He applies some of that study here, coming up with incisive observations about storytelling I’ve not seen made before. Offering advice on how to build a story, Silverberg does something wonderful and avoids the conflict word. I’ve discovered “conflict” is off-putting to some young writers, possibly because it suggests violence or supercharged stakes or overwrought emotions. Instead, looking back to the ancient Greeks, he frames story as propelled by dissonance:

Find a situation of dissonance growing out of a striking idea or some combination of striking ideas, find the characters affected by that dissonance, write clearly and directly using dialog that moves each scene along and avoiding any clumsiness of style and awkward shifts of viewpoint, and bring matters in the end to a point where the harmony of the universe is restored and Zeus is satisfied.

It’s not the final word on how to write a story, but it’s a surprisingly serviceable start.

Silverberg’s candor and generosity to the reader is so no-nonsense, he even reprints the rejection notes he received while canvassing science fiction magazines with his early work. Big-name writers usually dip into their rejection stack for the wrong reasons: to settle a score, or thumb their nose at those who stood in their way years past. Here, Silverberg reprints rejection slips that served to make him a better writer, admitting how he deserved them, and how he was often too young to take their advice at face-value.

Silverberg’s candor and generosity to the reader is so no-nonsense, he even reprints the rejection notes he received while canvassing science fiction magazines with his early work. Big-name writers usually dip into their rejection stack for the wrong reasons: to settle a score, or thumb their nose at those who stood in their way years past. Here, Silverberg reprints rejection slips that served to make him a better writer, admitting how he deserved them, and how he was often too young to take their advice at face-value.

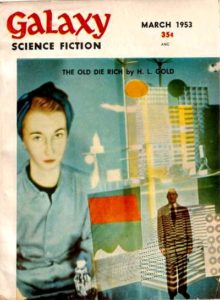

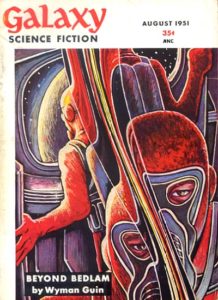

My favorite rejection letter comes from H. L. Gold, editor of Galaxy Science Fiction. Galaxy was a bit before my time (I grew up reading Analog, Asimov’s Science Fiction, and The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction). but Galaxy was well-known to me merely by its reputation. Galaxy was a “serious” science fiction magazine, known for avoiding the lewd subject matter and titillating covers the other science fiction magazines lured in readers with. (I’ve included a few of Galaxy‘s best covers here. The Internet Archive has a remarkable collection of back issues, covers and inside matter, that’s well worth perusing if you have any interest in science fiction’s past.)

Galaxy editor H.L. Gold sent Silverberg this rejection in 1956, when Silverberg had already broken into the field and was padding the back pages of science fiction magazines:

You’re selling more than you’re learning. The fact that you sell is tricking you into believing that your technique is adequate. It is—for now. But project your career twenty years into the future and see where you’ll stand if you don’t sweat over improving your style, handling of character and conflict, resourcefulness in story development. You’ll simply be more facile at what you’re doing right now, more glib, more skilled at invariably taking the easiest way out.

If I didn’t see a talent there—a potential one, a good way from being fully realized—I wouldn’t take the time to point out the greased skidway you’re standing on. I wouldn’t give a damn. But I’m risking your professional friendship for the sake of a better one.

Robert Silverberg was 21 when he received this remarkable letter, perhaps the greatest rejection letter of all-time.

Not too long ago I finished reading J. Hillis Miller’s On Literature, a slim and thoughtful consideration of the role of the written word at the end of the 20th century. Born from a lecture at UC Irvine in 2001, Miller expanded his talk into six chapters and 160 pages of conversational prose asking the simple but still-unanswered questions of literary theory: What is literature? Why read it? And how does it “work”?

Not too long ago I finished reading J. Hillis Miller’s On Literature, a slim and thoughtful consideration of the role of the written word at the end of the 20th century. Born from a lecture at UC Irvine in 2001, Miller expanded his talk into six chapters and 160 pages of conversational prose asking the simple but still-unanswered questions of literary theory: What is literature? Why read it? And how does it “work”?

The problem with describing fiction as a hyper-reality or virtual world is that these terms suggest science fiction. When I was young, one of my favorites books was Joe Haldeman’s science-fiction story collection Dealing in Futures. Its title instantly suggests that the book will generate for you any number of alternate worlds of a future time—that it’s “a pocket or portable dreamweaver.” Miller doesn’t limit this idea to science fiction, however. He sees all fiction as generators of virtual worlds.

The problem with describing fiction as a hyper-reality or virtual world is that these terms suggest science fiction. When I was young, one of my favorites books was Joe Haldeman’s science-fiction story collection Dealing in Futures. Its title instantly suggests that the book will generate for you any number of alternate worlds of a future time—that it’s “a pocket or portable dreamweaver.” Miller doesn’t limit this idea to science fiction, however. He sees all fiction as generators of virtual worlds.