Previously: Writer’s block

Next: A unique manifesto

The year that was 2020 will most likely go down as one of the most turbulent years of my life: The COVID-19 pandemic, lock-downs and masking, the murder of George Floyd and the ensuing riots, all leading up to the most contentious presidential election in memory that some still deny was properly tabulated.

In contrast, 2019 had been for me a rather productive year creatively, and I wound up publishing two novels in 2020 back-to-back: Stranger Son in April, followed by In My Memory Locked in June.

That aside, as 2020 trudged onward and the pandemic fevered on, it grew apparent normalcy would not make an appearance any time soon. I began to suffer a low-grade depression, a toothy rat gnawing at the ankles of my mental health. I needed to do something creative to keep a hold on my fragile state.

I made a personal goal of putting out a compact book—my previous two were unusually lengthy for me, with In My Memory Locked clocking in at 120,000 words. I had been binging on streamed movies (and who didn’t that year?) Viewing the masterful The Day of the Jackal motivated me to pick up Frederick Forsythe’s original novel, which I learned was inspired by his tenure as a journalist in Paris reporting on the assassination attempts made on Charles De Gaulle’s life.

I committed myself to write a taut thriller about the pandemic and lock-downs, short and sweet, with as little fat as possible, and saturated with paranoia and claustrophobia. The result was Man in the Middle, published in November 2020 and my most overlooked book. I’m proud of it, though, especially considering the conditions I was working under. I also believe it to be the first novel published expressly about the COVID-19 pandemic—but I cannot prove that.

As for blogging in 2020, I put out a number of short series which garnered some interest. At the start of the year, I did a mini-series on Dungeons & Dragons, including my take on Gary Gygax’s Appendix N, which was his book recommendations he included in the first AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide. Another series took at look at Hollywood novels, which gave me a chance to write on a few books I’ve been meaning to cover for some time, including The Day of the Locust and They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

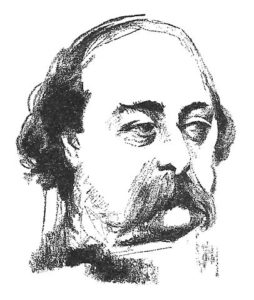

But the post I’m most proud of from 2020 regarded a bit of writing advice I’ve heard on and off for years now in writing groups and at writing conferences: “Use three senses to make a scene come alive.” Invariably, this advice is attributed to Gustave Flaubert.

As far as writing lore goes, this one is rather economical in expression. It’s also not altogether obvious why it’s true. Why three sense, and not four or five, or even two? The resulting blog post was satisfying to write because investigating the origins of this saying led naturally to explaining why it appears to be true.

There appears to be no evidence Flaubert ever made this statement, at least, not in such a direct manner. Rather, the textual evidence is that it originated from Flannery O’Connor, who in turn was summarizing a observation made by her mentor, Caroline Gordon.

Now, I’ve read many of Flannery O’Connor’s short stories—anyone who’s taken a few creative writing classes will eventually read “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” her most anthologized work. I had never read anything by Caroline Gordon, however, so it was fascinating to delve briefly into her work.

It’s a shame Gordon is not more well-read today. It’s probably due to her work not taking the tangents and experiments that other American modernists risked (such as Faulkner and Jean Toomer). She remained a formalist to the end. Her How to Read a Novel is an enlightening book, and while a tad dated, would make fine reading for anyone serious about writing a full-bodied, red-blooded novel.

Mostly, my pride for “Use three senses to make a scene come alive” is that it’s a solid essay: It starts out with an interesting question that leads to more questions, takes a couple of detours and unexpected side-roads on its journey, and ends on a note of successful discovery. It’s about all I can aspire to when I sit down to write.