In my last post on writing workshops, I discussed the Iowa format and three alternatives to it: Liz Lerman’s critical process, Transfer‘s submission evaluation, and playwriting workshops. Thinking about those alternatives led me to come up with a hybrid that I hope makes the fiction workshop more constructive.

This hybrid isn’t merely a group discussion structure, it’s a collection (or, less charitably, a grab bag) of suggestions for organizing a workshop. It’s geared toward informal peer workshops rather than academic settings, but some of its points might be useful there too.

I’ve grouped this grab bag into three sections:

- Organizing the group,

- managing manuscripts,

- and the group discussion itself.

Organizing the group

Define the goals of the workshop

For some, the primary goal of a writing workshop—perhaps the only goal—is to make their fiction publishable.

For others, a writing group is a place to receive direction and encouragement toward completing a larger project, such as a collection of short stories or a novel.

Some attend a workshop for the camaraderie, and to maintain a semblance of a writing practice in the face of hectic modern schedules.

Others write for themselves (or a small audience) and have no broader ambitions of mass publication.

For some people, it’s a combination of these things, and maybe more.

In my experience, almost all who attend a workshop go with the goal of eventual publication. But even if everyone agrees on that goal, it only raises more questions: Published where, and for what audience? Can any member in the group really claim knowledge of when a story is “publishable”? (And is there a difference between “ready for publication” and “publishable”?) Genre writers add a monkey wrench to the mix—someone who aims to be published by Tin House, The New Yorker, or The Paris Review might not the best arbiter of when a hard-military science fiction novel is ready for shopping around.

(Really, editors and publishers are in better positions to decide if a story is publishable or not. I was once told a story was unpublishable and weeks later landed it in a highly-regarded magazine.)

Liz Lerman’s process has some applicability here. As a baseline, agree that everyone in the group has an opinion of successful versus unsuccessful fiction, “success” being related to the quality of the work and not who might or might not publish it.

Also agree that everyone in the workshop is attending to make everyone’s fiction more successful, not merely their own.

How a writer uses that successful fiction—publication, independent distribution, blogging, or simply personal satisfaction—is the purview of the writer and not the group.

Agree what’s expected of each member

Most people join a workshop thinking they know what’s expected of them and everyone else. Rarely does everyone truly agree on those expectations.

On a basic level, people should understand they’re expected to

- read the manuscripts presented to the group,

- formulate some manner of thoughtful response,

- regularly attend meetings,

- and engage with the group discussion.

I’m not a big fan of merit systems, but some groups use them for motivation (such as “you must attend three meetings to submit one manuscript”).

Additional expectations are discussed below, but the point I’m making here is to verbalize (and even write down and share) these expectations. If you’re organizing a workshop for the first time, you might use the initial meeting to allow everyone to air what they expect from the others. Coalesce those points into a list that’s distributed to all members. Differing expectations can lead to headaches later.

Cover the workshop’s agreements with each member

For each new member, go over the group’s structure and policies and goals with all the other members present—in other words, don’t do it privately over email or the phone. This ensures that everyone’s on the same page. It also refreshes the memories of long-time members. Avoiding miscommunication is incredibly important in a workshop group.

Stick to your workshop’s structure unless everyone agrees a change is necessary (or, after a vote).

Don’t make exceptions. Exceptions kill the group dynamic. People begin to see favorites even if no favoritism exists. Remember: This is a peer group evaluating peer writing.

Manuscripts

Enforce page count and style

The era of the 25-manuscript-page short story may be receding (I wish it wasn’t), but that hasn’t stopped writers from penning them. The problem with bringing so many pages to a workshop is that people are bound to skim long work. That means they have less understanding of the story and are less qualified to discuss it. The peer pressure to discuss it remains, however, and so people will, leading to poor results.

I’ve brought in long work many times to workshops. In almost every instance I’ve heard comments (or outright griping) about the length. It seemed odd to me that writers would complain about having to read a measly 25 double-spaced pages, until I reminded myself they’re reading work they probably would not pick up on their own.

I’ve also noticed my shorter work almost always received higher-quality reads and discussion.

Some groups limit submission length to 20 or 25 pages. My suggestion is to go further and require manuscripts be no longer than 10 or 12 pages. Yes, that means having to split long short stories into two or three segments, but the writer will get a better read of those segments. Chuck Palahniuk’s writing group in Portland has such a page count restriction. Its members seem to have done fine by it.

Page count restrictions require basic, common-sense manuscript formats. Make it clear: Double-spaced, 1.5″ margins, 12-point Times New Roman, or whatever format your group decides.

I’ve seen writers game the manuscript format to subvert page counts. Don’t stand for it.

Agree on the role of manuscript edits

A lot of people in fiction workshops think there’s big value in marking up the manuscript itself. In the past, I’ve had manuscripts returned to me so marked-up I didn’t know what to make of them.

Readers drew lines like football plays over my pages, instructing me to cut sentences, split or combine paragraphs, rearrange scenes, and so forth. One workshop reader circled every instance of “has”, “had”, “is”, and “was” to alert me of my overabundance of passive voice, even where no passive voice existed. Others marked words wc (“word choice”), inserted and struck commas, semicolons, em-dashes, and so on.

Drawing attention to typos and misspellings is hard to argue against. Yes, if you see one, go ahead and circle it—but that’s gravy. Indicating confusion (“Who’s saying this?”) or highlighting passages that pop off the page have utility as well.

I’m arguing against line edits that are a matter of taste or philosophy. Telling me I should

- replace words not in the reader’s vocabulary,

- never use passive voice,

- only use “said” or “asked” as dialogue tags,

- drop all semicolons,

- strip out all adverbs, and so on,

are not the purview of the workshop reader. I would also argue these comments are counterproductive to a quality workshop experience. Too often the editorial mark-ups are writing lore masquerading as received wisdom (and usually associated with a well-known writer who purportedly counseled them).

On the flip side, I’ve encountered workshop peers who expected line edits, to the point of chiding some of us for not pointing out a typo he made. This attitude is counterproductive as well.

Assume everyone in the group is a capable writer. You are responsible for the fine-detail work in your manuscript, not the group. The workshop’s purview is to locate broader issues in the story and illuminate paths forward for your next revision. Workshops are not editorial services for you, the writer.

My experience has been that people who make fine-detailed edits to others’ manuscripts are expecting the same in return. When they don’t receive them, feelings begin to bruise and grudges are harbored. Notions of equal work loads and reciprocity is a major source of fracture lines in a workshop. (What’s worse are workshop members who don’t offer detailed proofreading of others’ work—but expect it from everyone else. Oof.)

If your group thinks it’s the purpose of the workshop to offer editorial changes, then make it an explicit policy. But I would suggest against it.

Agree on genre

Some fiction workshops will accept creative nonfiction, but rarely poetry or plays, if ever. Some will only accept fiction of a certain length (for example, no microfiction or novels). Some are for science fiction or mysteries, while others are open to all subject matter. I won’t argue one way or the other, but like my other suggestions, make sure everyone in the group is aware of the restrictions. For example, I’ve witnessed sparks where one member kept bringing prose poetry to a fiction workshop.

Agree on readiness

Some people will balk on this next point, but I’ll draw a line in the sand: The group should agree that the workshop isn’t there to critique first drafts. First drafts are too undeveloped and scattered to be productively critiqued in a group setting. Does it make sense to use other people’s valuable time to inform you of your first draft’s (usually obvious) problems? Especially when first drafts stand a high chance of being abandoned by the writer?

Likewise, late drafts are usually too set in concrete to receive any help from a workshop. If you’re unwilling to make substantial changes to the story, then asking the group to find its weaknesses is wasteful. (Never bring a manuscript to a workshop expecting unconditional praise. It never happens. Never.)

My rule of thumb: Workshops should be seeing stories after two or three drafts (or edit passes) and not after six or seven drafts/edit passes.

Some groups allow submitting work previously read by the group. I would add the proviso that the work must have received substantial edits since its last go-around. Other groups may prohibit it or require full agreement before accepting previously-seen work. As before, don’t make this up as you go. Choose a policy and stick to it.

No one should ever submit a published story to a workshop. Yes, people do this. (One possible exception to this rule: The story is up for republication and edits are requested by the publisher, i.e., it’s being anthologized.)

Formulate a written response format

Some groups may forgo written remarks, especially if the manuscript isn’t handed out ahead of time. Otherwise the response format should be agreed on by everyone.

I don’t mean page length (“one page single-spaced”), I mean what questions should be answered in the written response. It doesn’t have to be a fill-in-the-blanks approach. You could simply have a list of questions and ask each member to verify those questions have been answered (in one way or another) in their written response.

My suggestion? Use Transfer‘s system. Each reader writes on a 3-by-5 card a 1–2 sentence reaction to the story and uses the remaining space to describe its strengths and weaknesses. Use both sides of the card. Then the cards are read to the group verbatim. Readers will learn not to use the watered-down language so often found in a full-page responses (“I really like this piece,” or “This is strong.”) From there, launch into the general discussion.

If a 3-by-5 card seems too small a space, choose a longer format, but I still propose a length limitation to elicit thoughtful responses.

I’ve become convinced that the real magic in a fiction workshop lies in the discussion, not the written remarks. By giving each person only a sentence or two for strengths and weaknesses, the discussion can zero in on those thoughts and use them as a springboard for exploration.

The group discussion

Read the story aloud before discussing

As mentioned in my prior post, I noticed in playwriting workshops how reader-actors became invested in their characters. For fiction, even with an eight-page limit, it would take too much valuable group time to read aloud the entire manuscript.

What’s more, fiction is an inherently different experience than theater. A person reading a story aloud will not become as invested as an actor reading their part from a script.

Still, I’ve been in groups where a paragraph or two of the story was read aloud before the discussion, and it did seem to help. Getting the story into the air brings the group together around the manuscript. Everyone is hearing it one more time—the language, the setting, the narrator’s voice, the dialogue.

If your group meets every other week, it’s possible a few people haven’t read the story in ten or more days. (It’s also possible some read it in the Starbucks around the corner fifteen minutes earlier—there’s not much you can do about that.)

The writer shouldn’t read their own story aloud.

Keep the discussion to what’s on the page

Discuss the story as it’s written. Avoid peripheral issues (such as ideology or personal viewpoints) and comparisons to other work (other authors, television shows, movies, and so on).

Personal viewpoints are a good way to poison a discussion. Saying things like “I would never choose what the character chose here” isn’t useful. A better question is: Would the character choose what they chose? Everyone holds a subjective internal logic. Most of us hold several subjective internal logics. Does the character’s actions match their internal logic(s)? Was the suspension of disbelief lost?

While comparison to another work may seem harmless (“Your story reminds me of Mad Men“), popular culture is a kind of safe zone for people to retreat into. Pop culture will also derail a workshop discussion. When the harmless comparison takes over, all discussion becomes re-framed by it. Instead of discussing the story, the group is discussing how the story reads in light of this other work or issue. (“Mad Men focuses on women in the workplace. You could add more of that.”) The story becomes secondary. This is unfair to the author, who has brought their work in to be critiqued on its merits and weaknesses.

Workshop formats (including Liz Lerman’s) will often declare that readers shouldn’t make suggestions without the writer’s permission. This baffles a lot of people; if I’m not making suggestions, then what I am here to offer? Unearned praise and tender nudges? (Liz Lerman is not advocating either of these, I’m pretty sure.)

Rather than distinguish between suggestion and not-suggestion, I say keep the discussion to what’s on the page. Staying close to the page means, for example, suggesting the writer remove a spicy sex scene because it’s dragging down the story. Suggesting the writer remove a sex scene because that would make the story suitable for young adults—a hot market right now—is straying from the page. Both are suggestions, but the latter is not the purview of the workshop.

Maintain a discussion structure

The Iowa workshop format usually runs like this:

- Each reader gives a broad reaction to the story.

- A general discussion opens between the readers, with the writer only listening.

- The writer asks the readers questions.

Lerman’s approach is more involved and (as I discussed last time) more difficult to stick to, but it has some nice features worth including. For example, a workshop could be structured as so (incorporating some of the suggestions above):

- A portion of the story is read aloud by one of the readers.

- Each reader in turn reads their written remarks (or a summary of them) aloud. (This makes the 3-by-5 card approach more desirable.)

- General discussion by the readers. Keep the discussion to what’s on the page. Start with strengths, then move to weaknesses and confusion in the story.

- The writer is offered an opportunity to ask questions for clarification and prompt for suggestions.

- The writer summarizes what they’ve heard by naming new directions they plan to explore in future drafts.

- If the group is open to re-reading work, the writer can announce what changes they intend to make before submitting it next time. (This is probably more useful in a graded academic setting.)

This is not radically different from the Iowa format, but by specifying the goals of each step, they aim to direct the group’s energy toward better revisions and, hopefully, better writing.

Appoint a discussion leader

In academic settings, a discussion leader is naturally selected, with usually the teacher or an assistant taking that role. In informal workshops, the leader is sometimes the member who first organized the group, or has been around the longest. Otherwise, workshop groups will often lack any formal leadership.

Recognize the difference between an organizer and a discussion leader. Organizers solicit for new members, remind everyone when the next meeting will occur, arranges for a location to meet, send emails and make phone calls, and so forth. This is all important work (and harder than it looks) but it doesn’t imply that the organizer should lead the group discussion.

I suggest rotating the role of discussion leader around the group. Round-robin through the members, skipping writers when their manuscript is under discussion. (The writer whose work is under scrutiny should never be the discussion leader.) Or, if multiple writers are “under the knife” at each meeting, let the writer not under discussion lead the group, and then switch the role to the other writer.

Discussion leaders should monitor the group dynamic and gently remind people what stage they’re at, to keep the discussion on-track. Have leaders bring a watch to track the time and make sure everyone (readers and the writer) have a chance to speak. Make sure everyone knows that the leader has the right to interrupt someone if they’re going on for too long or taking the discussion down a hole.

The problem with round-robin is that some people simply aren’t good at this kind of role. (On the other hand, some people are too good at this kind of role.) This is where everyone has to step up to the plate—to rise a little to the occasion.

I’ve heard writers express disdain for discussion leaders, or any manner of hierarchical organization. I would love to agree, but experience has taught me otherwise. There’s tremendous value in having someone appointed to direct the flow of the conversation and cut it off when it’s deviating from the agreed-upon format. I’ve witnessed a few situations where such a leader could have saved a group discussion, and even the group itself.

If you’re organizing a workshop, or are in a workshop and looking for positive change, I hope this ignites ideas and discussion. If you use any of these ideas, let me know in the comments below or via the social networks.

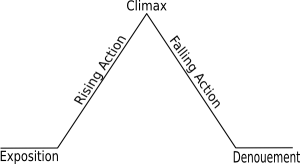

Between reading Field’s description of the midpoint, thinking of some examples in film and fiction, and my own experience, I see the midpoint as a Janus point in the story, a moment of looking backward and forward. Even if the storyline has wandered a bit (due to character development or a digression—any reason, really), the midpoint is a stitch connecting the beginning to the end.

Between reading Field’s description of the midpoint, thinking of some examples in film and fiction, and my own experience, I see the midpoint as a Janus point in the story, a moment of looking backward and forward. Even if the storyline has wandered a bit (due to character development or a digression—any reason, really), the midpoint is a stitch connecting the beginning to the end.

There’s countless guides, how-to’s, manuals, videos, and seminars on successful screenwriting. Syd Field’s Screenplay is, as I understand it, the Bible on the subject. First published in 1979, Field articulated his three-act structure (he calls it “the paradigm”) as a framework for telling a visual story via a series of scenes. Like literary theorists from Aristotle onward, Field recognized that most stories are built from roughly similar narrative architectures, no matter their subject or setting. In Screenplay he set out to diagram that architecture and explain how it applied to film.

There’s countless guides, how-to’s, manuals, videos, and seminars on successful screenwriting. Syd Field’s Screenplay is, as I understand it, the Bible on the subject. First published in 1979, Field articulated his three-act structure (he calls it “the paradigm”) as a framework for telling a visual story via a series of scenes. Like literary theorists from Aristotle onward, Field recognized that most stories are built from roughly similar narrative architectures, no matter their subject or setting. In Screenplay he set out to diagram that architecture and explain how it applied to film.