The workshop is so pervasive in the writing world it’s been converted to a verb: workshopping. Although workshops occur in disparate settings (academic, informal, living-room writing groups—whatever), a fiction writing workshop usually operates something like this:

A writer distributes their story or chapter to the rest of a group ahead of the meeting. Each workshop member reads the story on their own, away from the group. Each member writes a critical response, usually one page single-spaced. Often readers will mark up the manuscript as well: spelling, grammar, word choice, typos. They’ll highlight passages that are interesting or vivid, cross out passages that seem unnecessary or inappropriate, write question marks near confusing passages, and so on.

Then the group meets. The author quietly sits for twenty to thirty minutes while a half-dozen or more people critically pick apart what may be the most heartfelt and personal story he or she has ever written. The author is forbidden from speaking during this time. The discussion almost sounds as if the author is not present. He or she listens and takes notes while the rest of the room casually dissects hours, maybe tens of hours, of work. Just about any critical opinion that jumps to mind may be aired without fear of crossing a boundary. With the right people, it can be ruthless.

After the discussion, the writer may ask the group questions, and the session concludes.

Although I don’t know how this style of critique developed, I’ve often heard that it originated at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and so it’s called the Iowa workshop format. For better or worse, the Iowa model has become the platonic ideal of the fiction writing workshop.

For my purposes, the history of the format is not really important. It’s been handed down to us and dominates the critical process for fiction writers. It’s used in practically every living-room writing group and creative writing course in North America, from weekly adult-extension classes to top-tier MFA programs.

The format is not set in stone. I’ve seen a couple of home-brewed workshop formats, and even endured a writing group that made up the rules as it went along. Some established groups have a formal structure, but often it’s assumed everyone “knows” how to workshop. It’s rare to see the workshop where the group’s goals were enumerated and agreed upon by everyone.

A lot of time in writing workshops and a lot of negative experiences in them have led me to consider alternatives to the Iowa format. I can name three worth examining.

Liz Lerman

The most widely-used alternative to the Iowa workshop format originated in the world of modern dance. When a workshop organizer hands out their Xerox-of-a-Xerox-of-a-Xerox of Liz Lerman‘s Toward a Process for Critical Response, the phrase “dancing about architecture” leaps to my mind. I don’t mean to sound unfair—Liz Lerman’s critical format is so well-known and widely-used, it’s left the world of dance and crossed to fiction (and perhaps other arts). Obviously there are people other than myself seeking alternatives to the Iowa format.

I’ve enrolled in a handful of workshops where Liz Lerman’s process was used. In the first session, the leader selected workshop members to read aloud each section of Lerman’s process while everyone else followed along. Then the leader went over Lerman’s technique in detail, firmly and thoroughly discussing each stage, reiterating its emphasis on decorum, and above all its notions of fairness and neutrality.

For a fiction workshop, Lerman’s critical process structures the group discussion like so:

- The readers state what was “working” in the story.

- The writer asks question about their story. The readers answer the questions without suggesting changes.

- The readers ask the writer neutral questions about the story.

- The readers ask the writer for permission to offer opinions of the story.

Lerman’s process is designed to avoid confrontation at all costs. I would also say Lerman’s process requires a strong leader to guide the discussion along—a situation more suitable for an academic situation than a writing group of peers.

Unfortunately, the few groups I’ve been in that used Lerman’s process degenerated in a similar fashion. The first one or two sessions would follow Lerman to a T, but inevitably transgression of the format crept in. People would start questioning if they were “allowed” to say what they want to say. By the third session Lerman’s process all but disappeared from the radar screen. Steps got skipped. One stage would bleed into the next. Time ran out and the process cut short. (You need to go through each step for it to be worthwhile.) Sometimes the workshop turned into a pillow fight…the pillows filled with broken beer bottles.

I’m not blaming Lerman for this situation. Overall, her process is a positive one that emphasizes constructive criticism and neutral questions to give the dancer—or writer, or painter—a grab-bag of vectors for the next iteration of the creative process.

It’s just that I’ve never seen Lerman’s critical process consistently applied in a fiction writing workshop, academic or informal. Lerman’s process requires everyone to agree to it up front. Many people don’t, silently or verbally, either due to confusion (“Is this a neutral question?”) or rebelliousness (“I’m not here to sugar-coat my opinions”). Like so many group activities, if everyone doesn’t buy into the ground rules, problems sprout up.

Transfer magazine

One of the most positive workshop experiences I’ve enjoyed was as a staff member of Transfer magazine, a publication of San Francisco State University’s Creative Writing department.

Transfer used a blind submission process which solicited manuscripts from the student body. Manuscripts were distributed to the staff (20 or so students) who read them on their own and prepared note cards. On each card they described the story in objective terms and listed its strengths and weaknesses.

There’s only so much you can write on a 3-by-5 card. That limitation forced the staff to think hard about what they wrote, particularly since they might have to defend it later.

In group discussion, each story was evaluated in turn. The note cards became a launching pad for the discussion. The story’s author was not present, of course—editors and staff could not submit work. With the author’s name unknown to everyone present (including the editors), the discussion was remarkably fruitful and civil. Many of the manuscripts were teased apart by the group, revealing details and forces within them no single person had noticed on their own.

I’ve thought a lot about how to borrow some of this magic. There’s obvious problems with migrating this process to a standard fiction workshop. Even if the story’s author was asked to leave the room during the discussion, those present would know whose story was under the knife and that their remarks would eventually wind up in the writer’s hands. (Transfer‘s evaluation was not shared with the story’s author.) Anonymity fostered healthy discussion at Transfer, something not easily replicated in a weekly writing group.

On the other hand, the note cards and their space limitation garnered thoughtful responses from the students. The discussion, not the written responses, was where the real critical value lay. Most fiction workshops treat written vs. discussion as a 50-50 split. After Transfer, I’m not so sure.

Playwriting

Playwriting workshops have been another source of remarkably positive experiences for me. The differences between playwriting and fiction workshops are so marked, the first time I took a playwriting workshop I assumed it was a fluke of nature—a fantastical intersection of an energized instructor, great personalities, and wonderful writing. It was all those things, but I’ve enjoyed similar good fortune in the other playwriting workshops as well.

Unlike most Iowa-style formats, scripts are not distributed ahead of time in a playwriting workshop. Scenes are brought to the group and handed out on the spot. The playwright selects her “cast” from the other writers. The scene is performed cold, sometimes sitting at the table, sometimes using one side of the room as a makeshift stage. There is no blocking, no dramaturgy, no Method acting, but of course everyone gets into their roles a little.

The toughest part for me, as a fiction writer, was this part of the process. Public speaking is difficult enough; acting is painful, and I know I was hamming it up. It’s common for dedicated playwrights to take acting lessons, and many of them did my scenes great justice.

Once the scene is acted out, a general discussion follows. The discussions are rarely structured, nothing as formal as Lerman’s process. If there is structure in the workshop, it’s the leader asking “What’s working here?” and then “Okay, now where is it stumbling?”

Yet there was an extraordinary amount of generosity in those sessions. I never saw the backbiting or sniping that pokes its nose into fiction workshops. The energy level of playwrights is something to see—people eager, anxious even, to help the writer refine her work from something struggling to something great.

There are cultural differences between the world of fiction and the world of theater. Fiction writing is romanticized as an isolated act, and there’s truth in that. Plays are collaborative efforts, from start to finish, and it shows in a playwriting workshop. There’s also the stereotype of personality differences: fiction writers as introverts, theater folk as extroverts. But there were other fiction writers in my playwriting workshops. They shined too. It was the process, not the personality.

Reading a script aloud, cold, and in a performative manner engages everyone in the room. Too often in fiction workshops I’ve received written comments that were scribbled on the last page of my manuscript like it was a cocktail napkin. If the comments were assembled that sloppily, I can only imagine with what impatience my story was read.

Acting through a script makes people pay attention. It creates stakes in the room—the group feels they’re a part of the work, rather than exterior to or above it. The actors make special claims to the play, speaking up about their character’s motivations, speaking about their character in the first-person (“At that moment I really wanted to tell her what I knew”).

Again, like Transfer, I don’t know if this easily translates to the fiction workshop, but it’s worth knowing there are workable and practical alternatives to our age-worn practices. The question is how much of this magic can be adapted into a workshop process that has been pounded into place. That’s what I’ll discuss in my next post.

Next: A fourth alternative to the Iowa writing workshop format

Between reading Field’s description of the midpoint, thinking of some examples in film and fiction, and my own experience, I see the midpoint as a Janus point in the story, a moment of looking backward and forward. Even if the storyline has wandered a bit (due to character development or a digression—any reason, really), the midpoint is a stitch connecting the beginning to the end.

Between reading Field’s description of the midpoint, thinking of some examples in film and fiction, and my own experience, I see the midpoint as a Janus point in the story, a moment of looking backward and forward. Even if the storyline has wandered a bit (due to character development or a digression—any reason, really), the midpoint is a stitch connecting the beginning to the end.

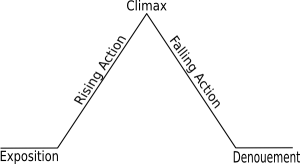

There’s countless guides, how-to’s, manuals, videos, and seminars on successful screenwriting. Syd Field’s Screenplay is, as I understand it, the Bible on the subject. First published in 1979, Field articulated his three-act structure (he calls it “the paradigm”) as a framework for telling a visual story via a series of scenes. Like literary theorists from Aristotle onward, Field recognized that most stories are built from roughly similar narrative architectures, no matter their subject or setting. In Screenplay he set out to diagram that architecture and explain how it applied to film.

There’s countless guides, how-to’s, manuals, videos, and seminars on successful screenwriting. Syd Field’s Screenplay is, as I understand it, the Bible on the subject. First published in 1979, Field articulated his three-act structure (he calls it “the paradigm”) as a framework for telling a visual story via a series of scenes. Like literary theorists from Aristotle onward, Field recognized that most stories are built from roughly similar narrative architectures, no matter their subject or setting. In Screenplay he set out to diagram that architecture and explain how it applied to film.