Not too long ago I finished reading J. Hillis Miller’s On Literature, a slim and thoughtful consideration of the role of the written word at the end of the 20th century. Born from a lecture at UC Irvine in 2001, Miller expanded his talk into six chapters and 160 pages of conversational prose asking the simple but still-unanswered questions of literary theory: What is literature? Why read it? And how does it “work”?

Not too long ago I finished reading J. Hillis Miller’s On Literature, a slim and thoughtful consideration of the role of the written word at the end of the 20th century. Born from a lecture at UC Irvine in 2001, Miller expanded his talk into six chapters and 160 pages of conversational prose asking the simple but still-unanswered questions of literary theory: What is literature? Why read it? And how does it “work”?

I almost didn’t finish the book, however, or even start it. Standing at the bookstore stacks pondering whether or not to purchase it, I almost returned On Literature to its place on the shelf after noticing the word “deconstruction” in its table of contents. Like a home cook who dabbles in books on nutrition, I enjoy reading how and why fiction works, but my patience runs low when I encounter the thick postmodern language of the deconstructionists and post-structuralists. As far as I’m concerned, literary theory veered into the weeds after the 1950s, becoming circular, reactive, insular, and insulated.

Miller’s On Literature does venture into deconstruction, but only briefly and in the most surprising way. Miller proposes C. S. Lewis’ Alice books were inadvertently deconstructing Robinson Crusoe, in the sense that Alice offers an unnatural world of random occurrence and contradictory logic. This pushes against the grain of Defoe’s orderly world, a world of British conquest over nature and British uplift of the “savage.” Connecting these two unrelated works typifies the kind of thoughtful playfulness that makes On Literature something much more refreshing than the dry lit theory of graduate studies.

As Wikipedia notes, Miller is an English professor specializing in deconstruction, and his academic work suggests the kind of dry examination of literature that most so-called average readers would not identify with. In On Literature, Miller loosens the knot in his tie to reveal a lifelong love of reading and all its pleasures.

But what’s most surprising is Miller confessing to seeing literature as a kind of virtual reality or “secular dream vision.” Miller argues fiction

is not, as many people may assume, an imitation in words of some pre-existing reality but, on the contrary, it is the creation or discovery of a new, supplementary world, a metaworld, a hyper-reality. … A book is a pocket or portable dreamweaver. [Emphasis mine.]

This is not a fashionable approach in academia today. It’s far more common to dissect literature with the scalpels of Marxism, feminism, post-colonialism, and gender and sexuality—in other words, to view fiction through the lenses of power dynamics and identity politics. And Miller goes farther than viewing books as portable virtual worlds. He proposes these hyper-realities are not merely witnessed by the reader, they’re entered magically when the book is opened and the first words begin to settle in his or her mind. Like the linking books in the video game Myst, a novel is a device that not only opens a door to an alternate reality, it allows us to dwell within its world, briefly.

The problem with describing fiction as a hyper-reality or virtual world is that these terms suggest science fiction. When I was young, one of my favorites books was Joe Haldeman’s science-fiction story collection Dealing in Futures. Its title instantly suggests that the book will generate for you any number of alternate worlds of a future time—that it’s “a pocket or portable dreamweaver.” Miller doesn’t limit this idea to science fiction, however. He sees all fiction as generators of virtual worlds.

The problem with describing fiction as a hyper-reality or virtual world is that these terms suggest science fiction. When I was young, one of my favorites books was Joe Haldeman’s science-fiction story collection Dealing in Futures. Its title instantly suggests that the book will generate for you any number of alternate worlds of a future time—that it’s “a pocket or portable dreamweaver.” Miller doesn’t limit this idea to science fiction, however. He sees all fiction as generators of virtual worlds.

Miller admits that this view of fiction has long been out of fashion in the academic world. He sometimes sounds a touch embarrassed admitting it, which is why I say the book reads more like a confessional than a treatise.

Over the years I’ve met writers who’ve told me they have little interest or use for books on how fiction “works.” To study literature is to kill the magic and pleasure of book-reading, the thinking goes—a notion that conveniently plays right into Miller’s “secular dream vision.”

On Literature recharged a personal theory I’ve been tossing around in my head for some time now. I don’t claim it’s original, but if I picked it up from somewhere, I couldn’t name the source. I don’t claim it’s an earthshaking theory either, but it has changed how I view books and my own writing.

The theory is simply this: Fiction is a controlled experiment being run by its author (or authors).

By “experiment” I mean something closer to trial-and-error than a formal scientific process. Books are not beakers of liquids bubbling over open flame. I also don’t mean the experimentalism of avant garde literature, the breaking of rules to create distance between the work and its reader, such as the mathematical formalism of the Oulipo. I mean an author playing “what if…?” The author imagines a world not their own to answer that question, and then, by writing the story, carries that experiment to its conclusion.

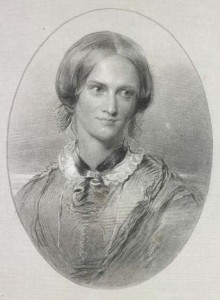

The “what if?” doesn’t have to be particularly daring or fantastical. “What if a young governess fell in love with her married employer?” could describe the experiment of Jane Eyre. In it, Charlotte Brontë constructed an experiment in experience—an experiment in the human condition, and told from a point of view not commonly disseminated up to that point in British literature. The experiment’s result is a document of 19th century countryside England, a world fairly foreign to us today but recognizable as a landscape of the human psyche. And thanks to Brontë’s experiment, we can visit that world without a time machine or other exotic technology.

When I say a “controlled experiment,” I mean controlled by the kind of restrictions Brontë imposed on herself throughout the creative process. Fiction is a plastic form. Brontë could’ve introduced any number of outlandish plot devices or characters. Instead, Brontë kept the novel’s details and events near to the world she knew and let the characters push through the complications themselves. Jane Eyre‘s ending is not clean and crisp, but it was under Brontë’s control. These decisions are guided by the hand of the author, controlling (but hopefully not dictating) the experiment’s outcome.

For an example of an experiment with a different set of controls, there’s Lewis’ Alice books. “What if my little friend Alice was transported to a world of playful illogic and word games?” Lewis gave himself the freedom to veer wildly from the known world. For one, the Alice in the books isn’t even the real Alice Liddell. And if gravity suddenly reversed itself in the Alice books, we wouldn’t be surprised at all.

On the other hand, gravity reversing itself would utterly destroy the experiment called Jane Eyre. Alice and Jane Eyre were written in the same time period by authors living a few hundred miles apart, but they ran very different experiments in what it means to be human.

Just as in science, not every experiment is a success. Some are duds. And Brontë did produce a dud of sorts: an experiment called The Professor, a novel about a male teacher at a Belgian all-girls school. The manuscript was rejected by every publisher she offered it to. Years later she tweaked the parameters of that experiment—tweaked the parameters of the experience—and wrote Villette, a novel about a female teacher at a Belgian all-girls school. Of Brontë’s works, The Professor is considered for completists and not widely read. Villette is thought by some to be Brontë’s true masterpiece.

This article is seven years old and the world has shifted. If we split imaginary writing into: pure entertainment, experimentalist, older haute couture and Marxist, the Marxist lens is overwhelmingly ascendant.

Like our political world, the literary world has split, with the ubiquitous Marxists drowning out all others.

Marxists assume anyone not supportive of their agenda is a bigot, and divide the world by ‘best’ rather than ‘bestseller.’ In other words, they presume the masses to be irrelevant.

I would call writing for the masses ‘genre’ fiction, and Marxists a derivative of ‘literary’ fiction. Through this lens I realize why I am drawn to genre. I can’t stand Marxists or haute couture.

But with all this said, what I most appreciate from your screed (ha!) is a realization that I can write genre fiction with an experimental spine and ignore the screaming harpies. The masses don’t give a **** about literary matters. But now I know there is someone else who comprehends experiment, an audience that will ask why without Marx or haute as their lens.

I draft fantasy stories with complex magic, then strip it all out, except for the experiment and the non-magical story. If I write about dragons there is a reason. Swords or rubber band guns would not do. You grok it. Cool.

And you grok how constrained I am. I must entertain and experiment. Story is—in search of self.

Write on, brother.