See the Introduction for more information on Twenty Writers, Twenty Books. The current list of writers and books is located at the Continuing Series page.

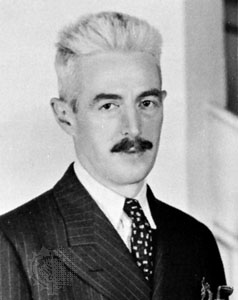

Dashiell Hammett

Earlier this year I wrote about “The Flitcraft Parable”, a story Sam Spade tells in The Maltese Falcon to Brigid O’Shaughnessy, the novel’s femme fatale. The parable is interesting for a number of reasons, but the central question that’s been attacked by readers and critics for almost a century is the purpose of its telling. Why does Sam Spade tell this odd story to O’Shaughnessy?

The story of Charles Flitcraft abandoning a secure life of money and family, only to return to a similar life in a different city, appears unrelated to the novel’s primary concern, the search for a bejeweled antique statuette. Some speculate Spade tells the story to O’Shaughnessy as a warning, that he knows she’s incapable of change and will continue lying to him, just as she’s lied in every encounter he’s had with her so far.

I don’t think the Flitcraft Parable is so simple. Before, I wrote about an academic connection I thought author Dashiell Hammett was making—that Charles Flitcraft’s assumed name, Charles Pierce, is a reference to philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce and Pragmatism, the school of thought Peirce founded. I’m the first to admit, it’s an egghead approach to a novel of murder and corruption, and one that Hammett probably didn’t expect a reader to delve terribly deeply into. That’s why I’m writing this post, a second look at the Flitcraft Parable, one that’s not so dependent on the headiness of nineteenth-century philosophy.

To be clear, I remain convinced Hammett intended to make a connection between Flitcraft and Charles Peirce’s philosophy. What I’m offering here is an interrelated interpretation of the Flitcraft Parable, an analysis that hews closer to the book’s plot and intentions without tossing out my first attempt.

If you’ve not read my first post, I’d recommend at least reading the section titled “The parable” before continuing. I’m not going to re-summarize the Flitcraft Parable here.

Warning: Spoilers ahead. In my prior post I attempted to avoid discussing the conclusion of The Maltese Falcon. It’s impossible for this post to do the same.

“The only formal problem of the story”

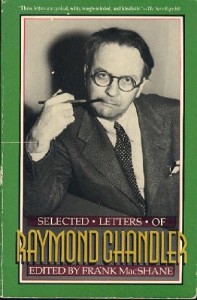

Raymond Chandler

Dr. Samuel Johnson was not Shakespeare’s first critic, but he was arguably Shakespeare’s first preeminent critic. Hard-boiled writer Raymond Chandler holds a similar relationship to Dashiell Hammett. In Chandler’s essay “The Simple Art of Murder” (first published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1944, fourteen years after the release of The Maltese Falcon), Chandler critiques and analyzes Hammett’s body of work, naming him as the one figure who represents the hard-boiled school of writing as its “ace performer.” He praises the forcefulness of Hammett’s prose and, most famously, how “Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people that commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse.”

Everything Chandler observes about Hammett’s writing can be applied to the Flitcraft Parable. Spade’s sparse language when telling the parable is as direct as darts puncturing a dartboard. The parable is constructed of fleshy people, people who do things for palpable reasons, even if those reasons are mysterious to us and based on an internalized logic we may never adopt.

Then, like Dr. Johnson’s best slicing analysis of Shakespeare, Chandler makes an off-the-cuff observation of The Maltese Falcon, tossing his insight before the reader’s feet as though embarrassed something so effortless must be mentioned:

…in reading The Maltese Falcon no one concerns himself with who killed Spade’s partner, Archer (which is the only formal problem of the story), because the reader is kept thinking about something else. [Emphasis mine.]

What Chandler alludes to here is the first murder in The Maltese Falcon. In Chapter One, Miles Archer, Spade’s partner, rushes to take leggy Brigid O’Shaughnessy’s assignment for his own; the kids today would call it a “cock block.” That night—Chapter Two—Archer is found murdered. This is the “formal problem” Chandler draws attention to in-between those parentheses.

More dead bodies arrive in The Maltese Falcon, bullet-ridden corpses shot up like a stop sign outside an Alabama roadhouse, but none of the murders are truly mysterious. The moment cold-fish henchman Wilmer and his pocket .45 cannons are introduced, it’s patent the murders are his handiwork. None of the other characters are capable of it. Dandy Joel Cairo and aristocratic Gutman are too drenched in Old World genteel for the blithe butchery Wilmer is thirsty to administer. O’Shaughnessy may have claws, but her true power lies in charming men to do her killing for her. Chandler’s on the money; the only formal problem in The Maltese Falcon is the death of Archer, a murder not so easily pinned on Wilmer.

Step back and admire this for a moment. Archer is the first murder in a mystery novel—and the detective’s partner to boot—yet Archer’s corpse is all-but-forgotten five pages after Spade identifies the body. Archer’s death remains, at best, a tertiary concern for another 175 pages. With the fluidity of a street con, Hammett misdirects our attention with Istanbul intrigue, the promise of a jewel-encrusted statuette, and hoary tales of the Knights Templar. Papering over Archer’s murder is an audacious and under-appreciated maneuver on Hammett’s part, one that demonstrates the confident control he maintains throughout the book.

Spade’s credo

The mystery of Archer’s murder may all but disappear after Chapter Two, but it comes roaring back in the final chapter. Spade confronts Brigid O’Shaughnessy, whom he’d told the Flitcraft Parable to earlier in the book, and states he knows she murdered Archer, pressing her and disarming her lies until she finally confesses.

In my prior post, I concluded that the Flitcraft Parable was a kind of manifesto for Spade, a declaration that he will eke out the truth of the matter, no matter the consequences. I also noted that

…Hammett wrote The Maltese Falcon in the third-person objective. Although Sam Spade is in every scene and the narrator stays close to him, we as readers are never privy to Spade’s internal thoughts. We can only guess what Spade is thinking at any moment. That’s the true mystery of The Maltese Falcon, not whodunnit, but What does Sam Spade know, and when does he know it?

Flatly, I believe Spade knows O’Shaughnessy had murdered Miles Archer when he tells her the Flitcraft Parable in Chapter Seven. I believe Spade suspects her as early as Chapter Two, when he views Archer’s body and takes a walk afterwards “thinking things over,” for all the reasons he names to O’Shaughnessy in the final pages.

If you view the Flitcraft Parable as a kind of manifesto or speech Spade is making for O’Shaughnessy, there’s one more speech Spade makes to her in the final chapter:

When a man’s partner is killed he’s supposed to do something about it. It doesn’t make any difference what you thought of him. He was your partner and you’re supposed to do something about it. … I’m a detective and expecting me to run criminals down and then let them go free is like asking a dog to catch a rabbit and let it go. It can be done, all right, and sometimes it is done, but it’s not the natural thing.

There’s a thin, near-invisible length of thread running between the Flitcraft Parable and the above, Spade’s credo.

The Flitcraft Parable, then, is Spade’s soft-sell to O’Shaughnessy. He’s telling her he’s a reasonable man. When Spade hears Flitcraft’s story of the falling beam, Spade agrees it seems reasonable, in it’s own way, for Flitcraft to abandon his wife and family–but he still returns to Mrs. Flitcraft to inform her what has happened to her husband.

Spade is accused of many things throughout The Maltese Falcon, some cold, some sordid, but with the Flitcraft Parable he’s quietly demonstrating to O’Shaughnessy that he will only bend so far. As he says in his credo, letting criminals go free “can be done, all right, and sometimes it is done.” He admits to her that Miles Archer “was a son of a bitch…you didn’t do me a damned bit of harm by killing him.” And then he hands her over to the police.

Would he have turned her in if she’d confessed earlier in the novel, after telling her the parable? It’s difficult to say, but the quiet way he tells it to her signals to me that he’s offering her a chance for redemption.

Chandler again, this time from his introduction to Trouble is My Business:

[The hard-boiled story] does not believe that murder will out and justice will be done—unless some very determined individual makes it his business to see that justice is done. The stories were about the men who made that happen. They were apt to be hard men, and what they did … was hard, dangerous work. It was work they could always get.

The Maltese Falcon is not a whodunnit, or a book about a statuette, or even a book about a private detective. It’s about a man who bears the weight of administering justice on-the-fly in a corrupt and mechanical world. Sam Spade holds two lives in his hands, Charles Flitcraft’s and Brigid O’Shaughnessy’s. Hard, dangerous work, work he could always get.

The Flitcraft parable cuts both ways, or, more accurately, all ways.

Flitcraft ends up with an almost identical life. BS (Brigid O’Shaughnessy) continues to lie, even to no real purpose. And Sam ends up doing what all Sam Spades must do: stand up for his partner, turn in the evil plotter, and protect himself to the extent he can.

It’s a form of fatalism: People don’t change much, maybe even in the end.

In The Thin Man, Hammett writes in Nick Charles’ voice: “Murder doesn’t round out anybody’s life except the murdered’s and sometimes the murderer’s.” This is a essential (not meaning ‘required’) philosophy for a fictional detective in a murder mystery.

Or for you and I?

“It’s a form of fatalism: People don’t change much, maybe even in the end.”

Perhaps, but I’m not so convinced that Charles Flitcraft didn’t change. From the way Spade tells the story, it tells me he did change. Let me put it this way — if Flitcraft didn’t change, do you think he will abandon his family again?

It doesn’t sound like he’s going to ever do that again; that in itself is change. And from the life he led before he abandoned his first family, running away for no reason at all (save for some mysterious significance of a falling beam), that strikes me as a major change as well.

Why do you believe Spade knows Brigid killed Archer when he tells her the Flitcraft story? If he only “suspects” her in Chap. 2, what happens, or what is said, in Chapters 2-6 to indicate Spade moves from “suspecting” to “knowing” ? Or do you merely assume Spade knows?

I’m assuming he knows. As I mentioned, one of the great puzzles of the book is “What does Sam Spade know, and when does he know it?”

As Spade explains later, he deduces Thursby did not shoot Archer merely by examining the body. His conclusion would apply to any of the other characters in the book he’s met by Chapter 6, save for Archer’s wife and Brigid. That, plus how often Brigid lies to him, and with such ease, are all issues Spade details in the final chapters as arousing his suspicions of her.

Thanks Jim, I’ve enjoyed reading your comments on the book. Of course, Spade never actually examines Archer’s body–he accepts the police description. I’m just hung up on the Flitcraft story and why he tells it to just Brigid, and why he tells it to her at that time…and also if Spade really knows who killed Archer before finally accusing her in the last chapter. I’ll keep reading. Thanks again.

Another way to look at it is that The Maltese Falcon is a religious allegory. Spade is described as looking like “a blond Satan.” Gutman is God the Father — “the G in the air” — who’s ready to sacrifice the man he regards as his son, Wilmer, in order to obtain a dubious treasure (mankind?). Spade tells the Flitcraft Parable to show that he believes life is random, not directed by a divine deity, and we only act like it isn’t because we don’t have beams falling on our heads every day.