Syd Field

(See my “Continuing Series” page for a listing of all posts about using Syd Field’s paradigm to write fiction.)

Last post I explained the fiction writer’s treatment (and how it’s different than a film treatment) as part of this series on how to use Syd Field’s three-act screenplay structure for writing stories and novels.

To recap, the first four questions you should ask yourself for the treatment are:

- Protagonist: Who is the main character of this story?

- Setup: What is the minimum of backstory, history, setting, or exposition that must be presented before the main story begins?

- Inciting Incident: What event disrupts the rhythms and rituals of the main character’s daily life?

- Plot Point #1: What reverses the main character’s daily life such that there is no easy return to normalcy? (Sometimes this is the Inciting Incident, but often it is not.)

Answering those four questions puts you at the halfway mark for writing your story’s treatment. Now I’ll go over the treatment’s final four questions.

Conflict: What is the primary or core conflict the main character faces?

Your answer to the prior two questions (Inciting Incident and Plot Point #1) should suggest an answer to this question. You might find yourself going back to re-answer this question later, when the story is firmer in your mind and the characters’ conflict better defined. For example, although Raisin in the Sun‘s core conflict would appear to be racism, a close reading of the play suggests the conflict is the family’s response to racism—will they keep their heads’ down or will they walk proud?

Assessment: What does the main character do to immediately resolve Plot point #1?

So far, the main character has experienced some kind of disruption (the Inciting Incident) and then an event that ensures they cannot walk away from that disruption (Plot Point #1). Whatever your character’s desires or motivations, they will still want to resolve their situation as quickly as possible. What action would they take?

I’ve learned that, in many ways, this is a crucial hinge to the success of a story. The Inciting Incident is often—almost always—out of the main character’s control. The no-going-back event (Plot Point #1) may be of their device, but it often is not. The Assessment is the main character locking into a course of action. This decision often determines the trajectory, shape, and flavor of the rest of the story.

Midpoint: What revelation or reversal of fortune occurs that permanently shifts the story trajectory?

As the name implies, this is an event which occurs approximately halfway through your story. Depending on the type of story you’re writing, this is often where the main character’s true antagonist is revealed or discovered, but that’s not a requirement. The purpose of this question is, in many ways, to keep the plates spinning—to prevent the character from getting too comfortable in this new situation, and to prevent you, the author, from digressing too far from the core conflict (which is terribly easy to do with longer forms, such as the novel).

Syd Field (the creator of the paradigm I’m riffing off of) explained in The Screenwriter’s Workbook that he “discovered” the Midpoint while analyzing Robert Towne’s screenplay for Chinatown. Field recognized that in Chinatown (and many other movies), something significant was happening around the middle of the film, but he couldn’t quite put his finger on what the event was, or why it was significant. In Chinatown, after much analysis, he realized the Midpoint was when the protagonist (private detective J. J. Gittes) discovers that the head of Los Angeles’ water company is married to the daughter of the founder of the water company.

At this Midpoint moment, almost all the questions and complications in the film have been introduced: an unsolved murder, the taint of corruption in Southern California’s water politics, and the detective himself being setup to unwittingly smear an innocent man in the press. At the Midpoint, we think we’re watching a murder mystery against the backdrop of 1930s city politics. J. J. Gittes discovery of the true relationship of the three central characters transforms Chinatown into a drama of a highly dysfunctional family. That’s what Syd Field (and this process) is asking for you to consider for your own story’s Midpoint. It’s the moment when you’ve laid all your cards out for the reader, the moment when the reader now recognizes what’s really at stake for your main character.

The Midpoint is more than a new complication. It’s a chance for you, the writer, to reveal that the story so far is not the whole story. Jim Thompson said there was only one kind of story: “Things are not what they seem.” The Midpoint is where you introduce revelations and reversals that open up the story in larger ways.

Plot Point #2: What dramatic or defining reversal occurs that leads toward a confrontation with the core conflict?

This part of the treatment is the furthest removed from the beginning of your story, and therefore one of the hardest to commit to paper.

Often when I’m writing I have a crystal-clear view of the story’s opening and a hazy idea how I want it to conclude. Finding the path between those two moments is what the process of writing is about. Plot Point #2 is where you make a statement about the final actions and decisions before the end of the story.

To make this easier, go back to what you wrote for Conflict (above) and re-read it closely. Then ask yourself how you think the story will end. You don’t have to commit to this, just get it down to see the words staring up at you from the page. But remember: this isn’t Plot Point #2. It’s where Plot Point #2 is leading toward.

Between those two points—the Conflict and your idea for an ending, however sharp or hazy—lies Plot Point #2. Like the reversal in the Midpoint, a story rarely arouses the reader when it’s predictable. Look for another reversal here: an unexpected shift that leads your protagonist from the middle of your story (Act Two) into the third act, where the final confrontation lies.

An illustration might help here. (Warning: spoiler alert.) Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle has many unexpected twists and turns—it’s easily Vonnegut’s most unpredictable novel—but the reversal that sets up the novel’s conclusion is when the protagonist is declared the San Lorenzo’s next Presidente by the dying dictator. This is not the conclusion of the novel, it’s the final complication in the character’s dramatic journey. (It’s important to realize that some complications are welcome by the protagonist, even though they might come back to bite him or her later.) With the protagonist’s ascension to El Presidente, all the bowling pins are in place, ready to be knocked down with godlike force in the novel’s stunning final chapters. This final complication is Plot Point #2.

Don’t worry if you currently lack Vonnegut’s clarity in your own character’s journey. Like the rest of this treatment, the goal here is to get ideas on paper and begin organizing the whirlwind of inspiration now circling your as-yet-unwritten story.

Take a breather

It looks like a lot, but you can craft a treatment in less than an hour. Give yourself time and space to do it. Don’t rush yourself, and don’t do it while distracted—no Internet, no television, no kids. Most importantly, write your treatment down. Like writing a contract, putting pen to paper forces hard decisions, engagement, and thoughtfulness.

When you’re finished, set your pen down and take a deep breath. When I write a treatment I often feel much like I feel after a sustained time writing prose: a bit exhausted, a bit lost, and more than a little exhilarated.

Remember, writing a treatment is writing. Don’t mistake this as an academic exercise. Organizing your thoughts on paper is as important as writing, editing, and polishing the final prose—it’s just a preliminary to those important steps. Writing a treatment is writing.

Next: Now write it again

Between reading Field’s description of the midpoint, thinking of some examples in film and fiction, and my own experience, I see the midpoint as a Janus point in the story, a moment of looking backward and forward. Even if the storyline has wandered a bit (due to character development or a digression—any reason, really), the midpoint is a stitch connecting the beginning to the end.

Between reading Field’s description of the midpoint, thinking of some examples in film and fiction, and my own experience, I see the midpoint as a Janus point in the story, a moment of looking backward and forward. Even if the storyline has wandered a bit (due to character development or a digression—any reason, really), the midpoint is a stitch connecting the beginning to the end.

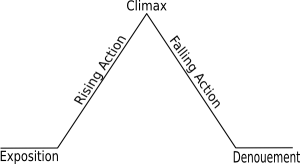

There’s countless guides, how-to’s, manuals, videos, and seminars on successful screenwriting. Syd Field’s Screenplay is, as I understand it, the Bible on the subject. First published in 1979, Field articulated his three-act structure (he calls it “the paradigm”) as a framework for telling a visual story via a series of scenes. Like literary theorists from Aristotle onward, Field recognized that most stories are built from roughly similar narrative architectures, no matter their subject or setting. In Screenplay he set out to diagram that architecture and explain how it applied to film.

There’s countless guides, how-to’s, manuals, videos, and seminars on successful screenwriting. Syd Field’s Screenplay is, as I understand it, the Bible on the subject. First published in 1979, Field articulated his three-act structure (he calls it “the paradigm”) as a framework for telling a visual story via a series of scenes. Like literary theorists from Aristotle onward, Field recognized that most stories are built from roughly similar narrative architectures, no matter their subject or setting. In Screenplay he set out to diagram that architecture and explain how it applied to film.