The final manuscript for Bridge Daughter was delivered to Kindle Press on Thursday and accepted by their editorial staff on Friday. The Kindle book is now officially in production. Everything is moving briskly.

Next from Kindle Press, they’ll notify me of Bridge Daughter‘s pre-order date and official publication date. If you nominated Bridge Daughter on Kindle Scout (thank you!) you’ll be able to download your free copy on the pre-order date—meaning you get to read the book before everyone else.

If you didn’t nominate Bridge Daughter (no worries), you’ll be able to order your copy on the pre-order date and receive your copy on the final publication date.

Paperback edition

I’m also happy to announce that a paperback edition of Bridge Daughter will also be available on Amazon. Conveniently, the paperback will be sold alongside the Kindle ebook (on the same page), so whichever edition is right for you is yours for the taking.

Pricing, dates, and other details for both editions are still in the works. Once I know, you’ll know, so stay tuned.

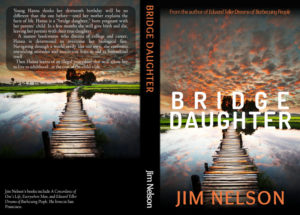

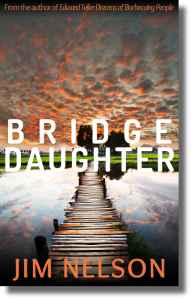

And now—miniature trumpet fanfare—I give you a cover reveal for the paperback edition of Bridge Daughter:

An hour ago I learned Kindle Press has accepted

An hour ago I learned Kindle Press has accepted