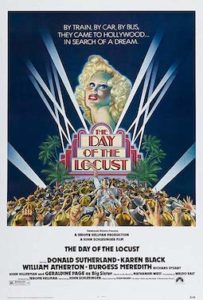

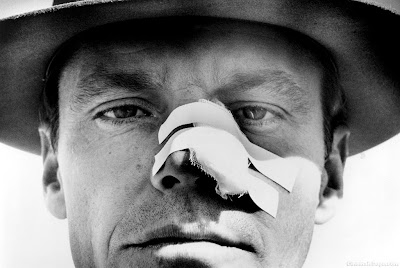

I’m not saying anything new when I say Chinatown is one of the greatest movies of all time. Producer Robert Evans captured lightning in a bottle when he put the 1974 film together, gathering a once-a-decade cast and an auteur director around a script familiar in Hollywood’s tones and tropes, and yet unlike anything preceding it.

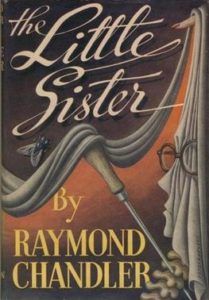

There’s a tragic timelessness to Robert Towne’s script, a movie nostalgic for a bygone Los Angeles and the wonderful movies it used to make. There’s an audaciousness to the script as well. Making a feature film about the California water wars sounds like a dead-weight clunker, a story laden with all the dramatic zeal of a C-SPAN documentary. Towne’s brilliant insight was to frame the drama as a 1930s private eye noir, and then add a horrific backstory of sexual abuse that the Hollywood of the 1930s could not have even hinted at.

Two drafts of the script are available at the Internet Archive, and it’s fascinating to compare them. The earlier version liberally layers on the film noir device of the detective wearily adding voice-overs. The detective is also more romantic toward the female lead, and less cynical overall. These were all dropped by the final version. Writers Guild of America rates the script as third on their list of all-time greats, behind Casablanca and The Godfather. That said, I bet if you plied a roomful of seasoned Hollywood screenwriters with free drinks, most would glumly admit they wished they’d written Chinatown, more so than the other two films.

The script is booby-trapped with one reversal after another. In the first act, a wealthy Mrs. Evelyn Mulwray hires detective J. J. Gittes to snoop on her husband’s illicit activities. Once the job is finished, Gittes is confronted by another wealthy woman, the real Mrs. Mulwray, who threatens to sue Gittes for defamation of character. These rug-pulls and sleights-of-hand continue throughout the movie, all to slow down Gittes as he hacks his way through a thicket of lies and secrets.

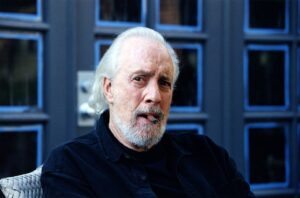

The sharpest observations I’ve encountered about the script come from Syd Field, a Hollywood writer best known for his books on the screenwriting process itself. (I’ve written about Syd Field several times before.) In his book Screenplay, Field thoroughly mines Chinatown for examples of strong storytelling. Here he makes his admiration plain:

A far as I’m concerned, Chinatown is the best American screenplay written during the 1970s. Not that it’s better than Godfather I or Apocalypse Now or All the President’s Men or Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but as a reading experience the story, visual dynamics, backdrop, backstory, subtext of “Chinatown” are woven together to create a solid dramatic unity of a story told with pictures. … What makes it so good is that it works on all levels—story, structure, characterization, visuals—yet everything we need to know is setup within the first ten pages.

But it’s in Field’s Screenwriter’s Workbook where he uncovers what I believe is the most original observation on Chinatown, and what may be the movie’s greatest secret. Field is explaining his concept of the “midpoint,” the scene in a movie that cleaves the second act down the middle, and creates connective tissue between the two halves of the film. As I wrote back in 2015, Field’s midpoint is “the moment when you’ve laid all your cards out for the reader, the moment when the reader now recognizes what’s really at stake for your main character.”

Field recognized Chinatown‘s midpoint wasn’t literally on page 64 of the 128-page script, but rather on page 54. It’s the scene where Gittes visits the Los Angeles water company to get more information on the murder of the department chief, Hollis Mulwray. As he studies the photos on the waiting room wall, Gittes deduces that Hollis’ wife Evelyn is the daughter of Noah Cross, the retired founder of the Los Angeles water company. That is, the three people central to the murder he’s investigating are closely-related family members.

Before this scene, we think we’re watching a Los Angeles murder mystery set against the backdrop of 1930s water politics. Gittes discovery of the true relationship of the three central characters transforms Chinatown into a drama of a grossly dysfunctional family.

If you watch carefully, you’ll see that the film makes a decided change in direction and tone after the midpoint. The questions of water rights dissolve into the background. The film’s remaining revelations almost all regard the Cross-Mulwray family’s dynamics. There’s a reason the movie’s second-most famous line is “She’s my sister and my daughter!”

This is Chinatown‘s big secret, the ace up its sleeve—the film sets us up to expect one kind of story, but by the end, we’re watching something very different. Like the question of who killed Sam Spade’s partner in The Maltese Falcon, the mystery of who killed Hollis Mulwray is neither important nor surprising. Water and money are simply a means to a tragic and rapacious end.

“What can you buy that you can’t already afford?” Gittes asks the villain near the close of the film.

“The future, Mr. Gittes!” is the reply. “The future!”