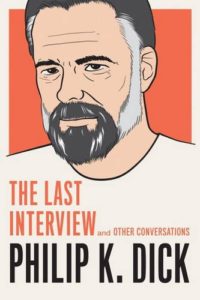

Recently I dove into the superb Philip K. Dick: The Last Interview and Other Conversations (from Melville House, publisher of the increasingly-intriguing Last Interviews collection) and am enjoying every page. I’ve written before about my semi-tortuous negotiations with PKD’s novels, and am finding some justification for my issues in these interviews with him.

Recently I dove into the superb Philip K. Dick: The Last Interview and Other Conversations (from Melville House, publisher of the increasingly-intriguing Last Interviews collection) and am enjoying every page. I’ve written before about my semi-tortuous negotiations with PKD’s novels, and am finding some justification for my issues in these interviews with him.

With PKD I remain hamstrung: he’s more speculative and philosophical than the run-of-the-mill hard sci-fi writer. This is right up my alley. I absolutely love PKD’s questions of existence, identity, and freewill that lay the foundations of his novels; and he’s a Bay Area writer to boot. Yet I find him to be a flawed writer, one who was so-very-close to writing perfect novels but had trouble overcoming basic hurdles, such as with cardboard characters and sci-fi’s obsession with “ideas” over story.

(For the record, my list of great PKD novels, in no order, remain A Scanner Darkly and The Man in the High Castle. I’m sure PKD’s fans find that list ridiculously short and astoundingly obvious. I still pick up his work now and then, so who knows, maybe I’ll find another one to add. PKD was more than prolific.)

In The Last Interview, PKD mentions to interviewer Arthur Byron Cover his early affinity for A. E. van Vogt. (I recall being fascinated with van Vogt’s Slan in junior high school, a book built from much the same brick as Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land.) PKD observes:

Dick: There was in van Vogt’s writing a mysterious quality, and this was especially true in The World of Null-A. All the parts of that book do not add up; all the ingredients did not make a coherency. Now some people are put off by that. They think it’s sloppy and wrong, but the thing that fascinated me so much was that this resembled reality more than anybody else’s writing inside or outside science fiction.

Cover: What about Damon Knight’s famous article criticizing van Vogt?

Dick: Damon feels that it’s bad artistry when you build those funky universes where people fall through the floor.

It’s like he’s viewing a story the way a building inspector would when he’s building your house. But reality is a mess, and yet it’s exciting. The basic thing is, how frightened are you of chaos? And how happy are you with order? Van Vogt influenced me so much because he made me appreciate a mysterious chaotic quality in the universe that is not to be feared. [Emphasis mine.]

It’s the questions after my emphasis that make the book’s back cover (“How frightened are you of chaos? How happy are you with order?”), and for good reason: They strike near to the heart of the questions asked in all of PKD’s work.

But I’m interested in the line about the building inspector. Damon’s review of Null-A is dismissively brief (although I suspect what’s being referred to here is Knight’s essay “Cosmic Jerrybuilder”). I’ve not read Null-A, but in principle I line up behind PKD on this one.

Reality is not as sane and orderly as many writers would have us believe. If I’m critical of contemporary American literature’s obsession with “hard realism”, it’s because I think PKD has put his finger on a deep and unrecognized truth: Reality is a fragile facade, but what a thorough facade it provides. It’s one thing for the average person to think they have total understanding of things they have no access to—the heart of a politician, the mind of a celebrity, the duplicity of a boss or coworker—but it’s truly tragic when a writer writes as though they have this reality thing all sewn up.

In contemporary literature, there are often moments where the narrator will have some moment of clarity into another person’s life. Usually this moment is presented as the epiphany, although it’s rarely epiphanic. (See Charles Baxter’s “Against Epiphanies” for a better argument on this point than I’m capable of producing.) Never mind that these pseudo-epiphanies are the inverse of contemporary lit’s obsession with quiet realism and slight personal movement. These mini-epiphanies are the literature’s cult of poignancy, and they’re often not interesting because they’re predictable, rational, and orderly.

There is chaos in our world, and it produces strangeness and unexpectedness that is neither poignant nor tied to fussy notions of realism. This, I think, is what PKD was referring to.

My only quibble with PKD’s observation is that I don’t see chaos as an external dark force in the universe. We are the chaos. We produce it. I’m less concerned about the wobble in Mercury’s orbit than the ability for just about anybody to murder given the right circumstances. (See the 2015 film Circle for an exploration of just that.)

The human psyche is like a computer performing billions of calculations a second. Most of the results are wrong, some are off by orders of magnitude, but the computer smooths out the errors to walk a thin line of existence and consistency. Even with these errors, the human psyche assures itself that its footing is steady and sure, when in fact it’s walking on the foam of statistical noise. The number of calculations it gets right are the rounding error.

The noise and errors do not matter. Our minds have the cognitive plasticity to bind contradictions into coherency. We can absorb chaos and make sense of it. This, I think, is close to the heart of PKD’s novels.

Update: Shortly after posting this I discovered Damon Knight partially backtracked on his criticism of A. E. van Vogt:

Van Vogt has just revealed, for the first time as far as I know, that during this period [while writing Null-A] he made a practice of dreaming about his stories and waking himself up every ninety minutes to take notes. This explains a good deal about the stories, and suggests that it is really useless to attack them by conventional standards. If the stories have a dream consistency which affects readers powerfully, it is probably irrelevant that they lack ordinary consistency.

Reading closely, Damon isn’t exactly agreeing with PKD’s comments (or mine, for that matter), but he does concede some flexibility on the supposed rigid strictures of fiction writing.