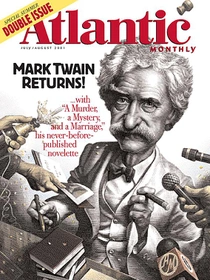

Will Blythe at Esquire asks, “In the golden age of magazines, short stories reigned supreme. Has the digital revolution killed their cultural relevance?”

Wearily, I started his essay expecting more of the same, and lo, finding it: Computers and the Internet, he contends, has done much to destroy literary fiction. By this point, I’m surprised any writer pursuing such a thesis would bother fortifying their argument with examples or statistics. Blythe does not fail on that count either: Other than some “c’mon, look around, you know what I’m saying,” the argument is made sans corroborative evidence. Of course the Internet has wrecked American literature. Why bother denying it?

It’s telling, then, that Blythe opens with the usual barrage of accusations about digital distractions—”Can you read anything at all from start to finish, i.e. an essay or a short story, without your mind being sliced apart by some digital switchblade?”—and then, to prove how things used to be so much better way back when, he segues to life as an Esquire editor in the 1980s and 90s:

[Rust Hill] and I would occasionally drink two or three Negronis at lunch, sometimes at the New York Delicatessen on 57th Street, and talk about the writers and novels and short stories we loved (and hated). … Then he and I would happily weave our way back to the office at 1790 Broadway, plop down in our cubicles and make enthusiastic phone calls to writers and agents, our voices probably a little louder than usual.

The jokes about fiction editors at a national magazine choosing stories to publish after a three-cocktail lunch write themselves, so I won’t bother. (Although I should, since, as an early writer, I had high hopes for placing a short story with a publication like Esquire. Perhaps I should have mailed a bottle of Bombay with each of my submissions.)

The dichotomy Blythe illustrates is telling: The hellish “after” is the mob writing Amazon user reviews and him not knowing how to turn off iPhone notifications; the blissful “before” is editorial cocktail lunches and not having to give a rat’s ass what anyone else thinks.

One counterpoint to Blythe’s thesis: The 1980s had plenty of distractions, including the now-obvious inability to silence your telephone without taking it off the hook. Another counterpoint: If you want to drink Negronis and argue literature over Reubens, well, you can do that today too. A third counterpoint: A short story printed in the pages of Esquire was sandwiched between glossy full-color ads for sports cars, tobacco, and liquor—most featuring leggy models in evening gowns or swimsuits. Distractions abounded, even before the Internet.

But none of these are what Blythe is really talking about. What he bemoans is the diffusion of editorial power over the past twenty years.

Blythe throws a curveball—a predictable curveball—after his reminisces about Negronis and schmears. Sure, computers are to blame for everything, but the real crime is that computers now permit readers to make their opinions on fiction known:

Writers and writing tend to be voted upon by readers, who inflict economic power (buy or kill the novel!) rather than deeply examining work the way passionate critics once did in newspapers and magazines. Their “likes” and “dislikes” make for massive rejoinders rather than critical insight. It’s actually a kind of bland politics, as if books and stories are to be elected or defeated. Everyone is apparently a numerical critic now, though not necessarily an astute one.

I don’t actually believe Blythe has done a thorough job surveying the digital landscape to consider the assortment and quality of reader reviews out there. There are, in fact, a plenitude of readers penning worthy critical insight over fiction. Just as there are so many great writers out there that deserve wider audiences, there also exist critical readers who should be trumpeted farther afield.

Setting that aside, I still happily defend readers content to note a simple up/down vote as their estimation of a book. Not every expression of having read a book demands an in-depth 8,000 word essay on the plight of the modern Citizen of the World.

Rather, I believe Blythe—as with so many others in the literary establishment—cannot accept readers could have any worthwhile expressible opinion about fiction. The world was so much easier when editors at glossy magazines issued the final word on what constituted good fiction and what was a dud. See also a book I’m certain Blythe detests, A Reader’s Manifesto, which tears apart—almost point by point—Blythe’s gripes.

When B. R Myers’ Manifesto was published twenty years ago, a major criticism of it was that Myers was tilting at windmills—that the literary establishment was not as snobbish and elitist as he described. Yet here Blythe is practically copping to the charges.

Thus the inanity of him complaining that today’s readers hold the power to “inflict economic power” when, apparently, such power should reside solely with critics and magazine editors. I don’t even want to argue this point; this idea is a retrograde understanding of how the world should work. This is why golden age thinking is so pernicious—since things used to be this way, it was the best way. Except when it’s not.

Of course the world was easier for the editors of national slicks fifty years ago, just as life used to be good for book publishers, major news broadcasters, and the rest of the national media. It was also deeply unsatisfying if one were not standing near the top of those heaps. It does not take much scratching in the dirt to understand the motivations of the counterculture and punk movements in producing their own criticism. The only other option back then was to bow to the opinions of a klatch of New York City editors and critics whose ascendancy was even more opaque than the bishops of the Holy See.

That said, it’s good to see a former Esquire editor praise the fiction output of magazines that, not so long ago, editors at that level were expected to sneer down upon: Publications such as Redbook, McCall’s, Analog, and Asimov’s Science Fiction all get an approving nod from Blythe.

But to cling to the assertion that in mid-century America “short fiction was a viable business, for publishers and writers alike” is golden age-ism at its worst. Sure, a few writers could make a go at it, but in this case the exceptions do not prove the rule. The vast sea of short story writers in America had to settle for—and continue to settle for—being published in obscure literary magazines and paid in free copies.

No less than Arthur Miller opined that the golden age of American theater arced in his own lifetime. Pianist Bill Evans remarked he was blessed to have experienced the tail end of jazz’s golden age in America before rock ‘n’ roll sucked all the oxygen out of the room. Neither of those artistic golden ages perished because of the Internet.

What caused them to die? That’s complicated, sure, but their demise—or, at least, rapid descents—were preceded by a turn toward the avant-garde. Which is to say, it became fashionable for jazz and theater to distance themselves from their audience under the guise of moving the art forward. The only moving that happened, though, was the audience for the exits.

Blythe then turns his attention to a third gripe in his meandering essay. Without a shred of evidence, he argues that the digital revolution of the last twenty-five years metastasized into a cultural Puritanism in today’s publishing world:

Perhaps because of online mass condemnations, there’s simply too much of an ethical demand in fiction from fearful editors and “sensitivity readers,” whose sensitivity is not unlike that of children raised in religious families… Too many authors and editors fear that they might write or publish something that to them, at least, is unknowingly “wrong,” narratives that will reveal their ethical ignorance, much to their shame. It’s as if etiquette has become ethics, and blasphemy a sin of secularity.

I cannot deny that there appears to be a correlation between the rise of the Internet in our daily lives and the shift over the last decade to cancel or ban “problematic” literature. What I fail to see is how pop-up alerts or a proliferation of Wi-Fi hot spots is to blame for this situation.

If Blythe were to peer backwards once more to his golden age of gin-soaked lunches, he would recall a nascent cultural phenomenon called “political correctness.” P.C. was the Ur-movement to today’s sensitivity readers and skittish editors. Social media whipped political correctness’ protestations into a hot froth of virtuous umbrage—a video game of oneupsmanship in political consciousness, where high scores are tallied with likes and follower counts. Using social media as leverage to block books from publication was the logical next step. But blaming computers for this situation is like blaming neutrons for the atom bomb.

After a dozen paragraphs of shaking my head at Blythe’s litany of complaints, I was pleasantly surprised to find myself in agreement with him:

The power of literary fiction—good literary fiction, anyway—does not come from moral rectitude. … Good literature investigates morality. It stares unrelentingly at the behavior of its characters without requiring righteousness.

At the risk of broken-record syndrome, I’ll repeat my claim that Charles Baxter’s “Dysfunctional Narratives” (penned twenty-five years ago, near the beginning of the Internet revolution) quietly predicted the situation Blythe is griping about today. Back then, Baxter noticed the earliest stirrings of a type of fiction where “characters are not often permitted to make intelligent and interesting mistakes and then to acknowledge them. … If fictional characters do make such mistakes, they’re judged immediately and without appeal.” He noted that reading had begun “to be understood as a form of personal therapy or political action,” and that this type of fiction was “pre-moralized.”

Unlike Blythe, Baxter did not fret that literary fiction would perish. Baxter was a creative writing instructor at a thriving Midwestern MFA program. He knew damn well that writing literary fiction was a growth industry, and in no danger of extinction. What concerned him was how much of this fiction was (and is) “me” fiction, that is, centered around passive protagonists suffering through some wrong. He noticed a dearth of “I” fiction with active protagonists who make decisions and face consequences.

As Blythe writes:

Too many publishers and editors these days seem to regard themselves as secular priests, dictating right and wrong, as opposed to focusing on the allure of the mystifying and the excitement of uncertainty. Ethics and aesthetics appear in this era to be intentionally merged, as if their respective “good” is identical.

If Blythe is going to roll his eyes at the glut of reader-led cancellations and moralizing editors, perhaps he could consider another glut in the literary world: The flood of the literary memoir, with its “searing” psychic wounds placed under microscope, and its inevitably featherweight closing epiphany. These testaments of self-actualization may be shelved under nonfiction, but they are decidedly fictional in construction. In the literary world, stories of imagination and projection have been superseded by stories of repurposed memory, whose critical defense is, invariably, “But this really happened.”

It was not always so. Memoir was once synonymous with popular fiction. Autobiography was reserved for celebrities such as Howard Cosell and Shirley MacLaine, or a controversial individual who found themself in the nation’s spotlight for a brief moment. It was not treated as a high art form, and perceived in some quarters as self-indulgent. No more.

There remains an audience for great fiction. Readers know when they’re being talked down to. They know the difference between a clueless author being crass and a thoughtful author being brutally honest. They also know the difference between a ripping yarn and a pre-moralized story they’re “supposed” to read, like eating one’s vegetables.

The death of literary fiction—especially the short story—will not be due to iPhone notifications and social media cancellations. Perhaps the problem Blythe senses is the loss of a mission to nurture and promote great fiction. The literary world has turned inward and grown insular. Its priorities are so skewed, I’ve witnessed literary writers question if fiction can even be judged or critiqued. The worsening relationship of class to literary fiction should not be overlooked, either.

If Blythe laments Asimov’s Science Fiction, perhaps he should check out the thriving Clarkesworld. Substacks of regular short fiction are regularly delivering work to thousands of readers. I don’t know if these publications’ editors are gulping down Negronis during their daily Zoom meetings—but as long as they’re putting out quality fiction that challenges and questions and enlightens, maybe that doesn’t matter, and never did.