Among fiction writers, the editing process is notoriously dreaded as drudge work, but revision is where the magic happens. It’s where a struggling, plodding story is shaped into the author’s vision.

Recently I discovered “How Star Wars was saved in the edit”, an impressive and succinct video on the high art of film editing. It demonstrates revision so well, it should be required viewing in creative writing courses everywhere.

That’s right: Creative writing. Even though it regards film editing, almost all the techniques described have application in revising fiction.

To clarify, I’m not talking about the Star Wars story line. The formula behind Star Wars has been so imitated and overdone over the past forty years, there are few morsels left to claim as one’s own. Narratological analyses of George Lucas’ little sci-fi flick are bountiful, as are the reminders how he borrowed much of his structure from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero With a Thousand Faces. All of this is well-trod ground and not what concerns me here.

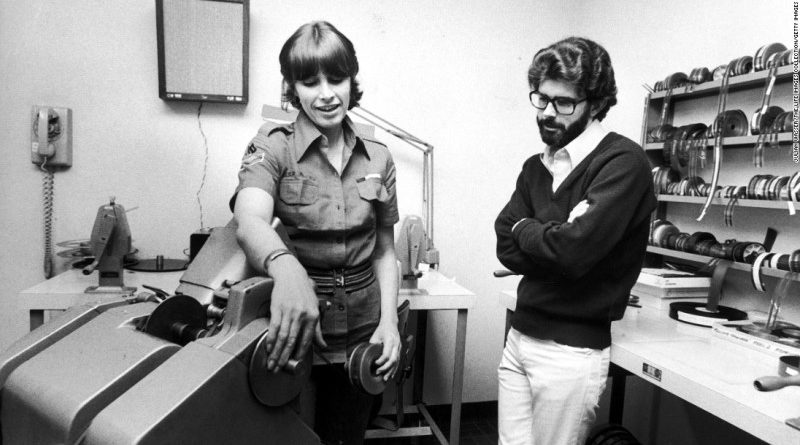

What “Saved in the edit” highlights is a criminally unknown aspect of Star Wars‘ mega-success: The role of Lucas’ then-wife Marcia in sculpting the movie’s rough cut into a blockbuster. If Marcia Lucas had applied her formidable editing talents solely to the movie’s heart-pounding conclusion (the rebel attack on the Death Star), she would have deserved the Oscar for editing she eventually received. Her contributions went far deeper, it turns out.

Ordering scenes

I’m most interested in two of the video’s sections. The first is the explanation of intercutting (or cross-cutting), starting at 6m50s in the video. Intercutting is a film term referring to a specific editing technique. For fiction, a more general (and blander) term would be scene ordering.

Marcia Lucas and her fellow editors crispened the first act by reordering scenes to better establish the story and get the audience involved. Since viewers are able to fill in blanks on their own, the reordering allowed for the removal of entire scenes, keeping the story line brisk and taut.

Revising scene order is the author at her most godlike. She is rearranging the events of her dreamworld like a child building up and tearing down sand castle turrets. Scene reordering requires bold moves and wide peripheral vision. It’s not about word choice and tightening dialogue, it’s asking if each scene is in the right place at the right time—or even if it should be included at all.

(Another visual medium that uses visual cuts effectively is comics, a topic I’ve explored before.)

My latest (and, as of today, unpublished) novel offers a personal example of scene reordering in my editing process. My early chapters were a mess. The main character was traveling quite literally in circles. An early reader (and good friend) pointed out the wasted time and lack of energy in the first act.

Although I like to make a rough outline when I write a novel, I don’t organize down to the scene, or even the chapter. After hearing my friend’s criticism, I went through the draft and produced a rough table of contents. Each chapter was listed with a brief one- or two-sentence summary of its major plot points. (A writing notebook, even a digital one, is a good tool for this task.)

Thinking of his complaints, and referring to my makeshift table of contents as a guide, I “re-cut” the opening chapters and produced a sleeker first act. Sections of one chapter were lifted and dropped into another chapter. Events were shuffled to tighten the story, sharpen focus, reduce transitions, and get the story on its legs. Thousands of words wound up on the cutting room floor, so to speak. It was worth it.

Ordering beats

My other interest in “Saved in the edit” regards the first meeting between Luke and Obi-wan (11m50s in the video):

Originally the scene started with Luke and Obi-wan watching the princess’ message, then they play with lightsabers, and then they consider to go help her.

The editors realized how “heartless” this scene played out due to the lag between hearing Leia’s holographic plea and discussing whether or not to help her. They reordered the scene by opening in medias res to make it seem the two have been talking about Luke’s father for some time. From there,

- Obi-wan shows Luke the lightsaber,

- they watch Leia’s message,

- and then they argue about flying off to help her.

It’s a simple change, which is kind of the point: Sometimes vital edits are not complex or massive, but surgical and subtle. What’s more, notice how this edit did not require re-shooting the scene. All the elements were in place, the problem was their presentation.

The new ordering creates an emotional cone. The tension starts low with exposition (Luke’s supposedly-dead father, a forgotten religion that tapped into a mysterious cosmic “force”). The stakes rise in pitch as they watch Leia’s plea. A tension point is reached when the old man in the desert tells Luke he must drop everything and travel across the galaxy to save a princess.

If you find a scene you’re working on meandering or feeling aimless, consider how the tension rises within it. Is it building, or is it wandering around?

In play-writing, the basic unit of drama is called a beat. A beat consists of action, conflict, and event. Marcia Lucas improved the scene with Luke and Obi-wan by unifying a beat that had been split apart with the lightsaber business:

- Action: Obi-wan wants Luke to learn the Force and save the princess;

- Conflict: Luke has to stay and help his uncle with the farm;

- Event: Luke refuses Obi-wan’s call and goes back to the farm.

Not all edits are rearranging action/conflict/event. If you think of a scene as a collection of little beats, sometimes revision is moving the beats around, much as scenes can be reordered.

One sin I’m guilty of is opening a chapter with the character in the middle of action or a conversation, then dropping to flashback to explain how the character wound up in this situation, then returning to the scene. It’s a false and inauthentic way to start chapters in medias res.

How to correct this? Sometimes by moving the flashback to the start of the chapter and rewriting it in summary. Often I drop the flashback and assume the reader will catch up on their own (as Marcia Lucas did by opening the Obi-wan scene in the middle of the conversation). Each edit is situational and requires a film editor’s mindset. Simplifying scenes is the core of powerful revision.

These editing skills really should be the stock-and-trade of every novelist and playwright. Yet I’ve never seen a book on writing fiction explain these points as ably as “Saved in the edit”. It’s unfortunate it takes a YouTube video on the making of Star Wars to lay out the power of editing in such a lucid and compelling way.

Writing a book is like being an all-in-one film crew. The author is director, screenwriter, editor, and casting agent. The author plays the roles of all the actors. The directing and writing and acting is the fun part, or at least it can be. But editing is where a manuscript goes from a draft to a novel.

Further reading

For more on Marcia Lucas, I suggest starting with her biography at The Secret History of Star Wars. It details the shameful way she was written out of the history of the movie after divorcing George Lucas.

“Marcia Lucas: The Heart of Star Wars“ is another fine YouTube video, focusing more on her career and her role with other 1970s films you’ll recognize, such as Taxi Driver and The Candidate. It also does a nice dive into Marcia Lucas editing American Graffiti into the phenomena it would become.

Marcia Lucas’ influence on Hollywood and film editing is still felt today. The Beat‘s “5 Editors That Broke the Hollywood System” are all women, including Marcia Lucas, even though the article is not specifically about women in film history.