Kat Rosenfield at Unherd claims she knows why men are no longer wild: “Our sense of adventure died with Chris McCandless.”

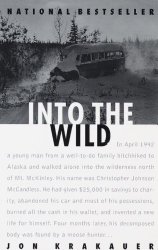

I last wrote about the mythology around Chris McCandless and Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild in 2015. Rosenfield’s article motivated me to survey the situation once more.

I won’t summarize here Krakauer’s book or Chris McCandless’ life and death. My earlier blog post (“Into the Wild and the continued fascination with Christopher McCandless’ death”) covers both. Wikipedia articles on the book and the man are good starting points too. And there’s no substitute for reading Into the Wild itself.

Why men are no longer wild

The meat of Rosenfield’s argument lies within this claim:

McCandless’s story became the object of fascination — and not long after that, backlash. His life was either an inspiring example of indomitable American spirit or a nauseating waste of privilege and opportunity; his death was either a tragic accident or an idiotic, avoidable bit of foolishness.

My motivation for this post started right there, in the above assertion. Compare it to what I wrote in 2015:

If this framing—reckless versus romantic—sounds wearily familiar, it’s because the debate over McCandless’s death has become nothing more than a flash-point in a broader argument we’ve had in America since he and I were born…

McCandless’ life has been converted into a proxy for this country’s culture wars, a string of battles where no one—no one—raises the white flag. … I’m unable to see how this situation honors or respects Christopher McCandless’ life.

Eight years later, Chris McCandless is still serving as a proxy for whatever culture war debate is on our collective brains at the moment. His life and death, cleansed and romanticized, provide a mythic framework to hang any number of ideological flags: anti-materialism, anti-woke, anti-technology, anti-Americanism, anti-capitalism, and more.

This is vital to recognize. Culture war ushers in an inevitable and putty-like transitive logic: Criticism of Krakauer is interpreted as an attack on McCandless; criticism of McCandless is read as an attack on his values; criticism of McCandless’ fans is an attack on progressivism; and so on.

So, yeah, I have and will criticize Krakauer, the actions of some of McCandless’ legions of fans, and the politicization of Into the Wild. I’ll even criticize some of McCandless’ choices. I’m trusting you to recognize that doesn’t make me a “Chris hater.”

“He’s emerged as a hero”

From there, Rosenfield takes what has become a standard approach in modern rhetoric: She claims her reasonable and clear-eyed position is the one under attack, even if she has trouble locating the hordes mounting said attack:

The lumping-together of McCandless with Thoreau was inevitable, and not just because the latter was a major inspiration for the former: here was an expression of the timeless desire to take these icons of male self-sufficiency down a peg. Today, the mention of either man tends to elicit a snarl — but the bulk of the anger is saved for McCandless, fuelled by a contemporary media ecosystem that keeps finding new ways to tell his story. [Emphasis mine.]

I cannot recall anyone “snarling” over Thoreau, who remains required reading in American high school and university curricula. He may have been dismissed in his time as a fraud or a crank, but I’m pretty sure Thoreau’s preeminence in American culture and letters is secure.

As for McCandless, Into the Wild has been translated into thirty languages and has remained in print since it was first published in 1996. It was made into a major motion picture by Sean Penn. It’s on high school and college reading lists across the nation, and was selected by Slate as one of the best nonfiction books of the past twenty-five years. A web site dedicated to Chris McCandless (christophermccandless.info) is still going strong, hosting papers written by young people affected by McCandless’ life story, a memorial foundation, a documentary, and more. The PBS special “Return to the Wild” promised to “probe the mystery that still lies at the heart of a story that has become part of the American literary canon and compels so many to this day.”

Yet Rosenfield somehow concludes McCandless and his life story are under a brutal and withering assault. If the debate could be placed on a scale like produce aisle apples, I’m certain we’d find any snarling criticism of Chris McCandless and Jon Krakauer is far outweighed by McCandless’ legions of fans and sympathetic media sources.

It doesn’t help that Rosenfield’s adoring portrayal of McCandless as the kind of masculinity we need more of in our on society is framed just as she outlined at the top of her article: “His life was either an inspiring example of indomitable American spirit or a nauseating waste of privilege and opportunity.” There are no alternatives, apparently.

“But lately,” she writes, “the controversy surrounding McCandless as a mythological figure is no longer an accompaniment to the story; it is the story.”

I don’t know that “lately” part is true. The controversy around McCandless began almost immediately after Krakauer’s story was published in Outside magazine. Its editors reported they’ve never received as much mail about a single story, before or since. The controversy became the focus of all subsequent accounts of Chris McCandless for the same reason Twitter melted down over the color of a dress: People couldn’t believe any sane person would disagree with their interpretation—and if you did, there was something wrong with you.

Here’s a good question: Why is McCandless a mythological figure? He was a human being, “full of vim and vigor, a complicated young man of effusive talents, predictable weaknesses, and eccentric foibles,” as I wrote in 2015. We can valorize a man, we can valorize his values. Why valorize his avoidable death?

Sherry Simpson of Anchorage Press put it this way in 2003:

Much of the time I agree with the “he had a death wish” camp because I don’t know how else to reconcile what we know of his ordeal. Now and then I venture into the “what a dumbshit” territory, tempered by brief alliances with the “he was just another romantic boy on an all-American quest” partisans. Mostly I’m puzzled by the way he’s emerged as a hero, a kind of privileged-yet-strangely-dissatisfied-with-his-existence hero.

I don’t agree with the “death wish” angle, nor do I think he was a “dumbshit” for entering the Alaskan interior. (I would say “grievously unprepared.”) “An all-American quest” ticks a few of my personal checkboxes, as does “I’m puzzled by the way he’s emerged as a hero.”

The diary

In an aside, Rosenfield complains that McCandless’ sister’s memoir The Wild Truth (2014) has been weaponized: “It was received less as additional context to his story than a debunking of it: McCandless wasn’t a latter-day adventurer, he was a spoiled trust-fund kid with daddy issues.” (It would have helped if Rosenfield could have linked to an actual “debunking.” The single link she provided goes to a perfunctory summary of the memoir by USA Today.)

Carine McCandless does offer eye-opening “additional context” to Chris’ story. The real issue her memoir introduces is that Krakauer agreed to withhold these key details from Into the Wild at the request of the family. By doing so, Krakauer created a hole in his narrative and in our understanding of McCandless’ motivations. The Wild Truth was not weaponized for a mass “gotcha” campaign, or if it was, the campaign made not a dent on the beatification of Chris McCandless. Rather, as with the evolution of the poisonous seeds (explained below), its details were smoothed over by sympathetic media sources as completing and supporting Krakauer’s story, and further buttressing the McCandless hagiography.

The only “debunking” of note was from McCandless’ parents:

“After a brief review of its contents and intention, we concluded that this fictionalized writing has absolutely nothing to do with our beloved son, Chris, or his character,” they wrote. “The whole unfortunate event in Chris’s life 22 years ago is about Chris and his dreams—not a spiteful, hyped up, attention-getting story about his family.”

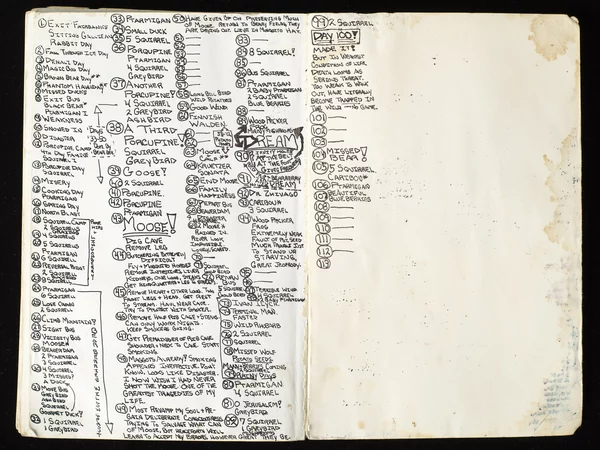

There was another narrative hole, though, that is more substantial and of far more interest to people like me: The contents of the journal McCandless kept while in the Alaska wilderness. Initially only Krakauer had access to the diary, which he used while writing Into the Wild.

When the journal was finally released, it amounted to

approximately 430 words, 130 numbers, nine asterisks and a handful of symbols. Other than this, all Krakauer had to go on was several rolls of film found with the young man’s body and a rambling, cliche-filled, 103-word diatribe carved into plywood in which McCandless claimed to be “Alexander Supertramp” off on a “climatic battle to kill the false being within and victoriously conclude the spiritual pilgrimage.”

Craig Medred of Anchorage Daily News has much more to say about “the fiction that is Jon Krakauer’s Into the Wild“. That Krakauer reconstructed McCandless’ last weeks in minute detail from such sparse documentation should be a flare in the sky to anyone who still believes the label “nonfiction” means something.

“It is as if the late writer Ernest Hemingway found a 430-word journal written by Nick Adams containing the words ‘railroad,’ ‘fish,’ ‘forest fire,’ ‘camp’ and a few others,” Medred writes, “and from that wrote ‘Big Two-Hearted River’ as the true story of Adams’ biggest fishing adventure.”

If that sounds like hyperbole, then reread the final three chapters of Into the Wild and reckon them against the source material Krakauer was drawing from. Here’s a portion of the journal, from the McCandless’ memorial site:

Day 2: Fall through the ice day. Day 4: Magic bus day. Day 9: Weakness. Day 10: Snowed in. Day 13: Porcupine day…. Day 14: Misery. Day 31: Move bus. Grey bird. Ash bird. Squirrel. Gourmet duck! Day 43: MOOSE! Day 48: Maggots already. Smoking appears ineffective. Don’t know, looks like disaster. I now wish I had never shot the moose. One of the greatest tragedies of my life. Day 68: Beaver Dam. Disaster. Day 69: Rained in, river looks impossible. Lonely, Scared. Day 74: Terminal man. Faster. Day 78: Missed wolf. Ate potato seeds and many berries coming. Day 94: Woodpecker. Fog. Extremely weak. Fault of potato seed. Much trouble just to stand up. Starving. Great jeopardy. Day 100: Death looms as serious threat, too weak to walk out, have literally become trapped in wild—no game. Day 101-103: [No written entries, just the days listed.] Day 104: Missed bear! Day 105: Five squirrel. Caribou. Day 107: Beautiful berries. Day 108-113: [Days were marked only with slashes.]

McCandless notes on day 69, six weeks before his death: “Rained in, river looks impossible.” (I assume he means the river between him and civilization looks impossible to cross.) On day 100, he realizes “have literally become trapped in wild.” Earlier he writes, “Lonely, Scared.” Earlier still, he writes, “Weakness.”

“Male self-sufficiency”

McCandless entered the Alaskan wilderness packing ten pounds of rice, a .22-caliber rifle, ammunition, a camera, and a selection of books. Although his exact date of death is unknown, it appears he only survived for 113 days, or about sixteen weeks. All evidence is that he leaned heavily on a single food source, the seeds of a wild plant.

Rosenfield takes a crack at those who knock McCandless as unable to distinguish a moose from a caribou (“He could, actually”), although that’s beside the point. The real failure was him bagging a beast and lacking the skills to preserve it. After mere days he lost the carcass to maggots. Properly preserved, the meat and organs could have fed him for months, providing him with vital protein and fat. He wrote the waste was “one of the greatest tragedies of my life,” one of the few lucid and complete entries in his journal. Other than the wild seeds, he appears to have had no success in securing an additional food source.

The usual rejoinder to these failures is that the seeds he foraged were a good source of nutrition but, due to understandable circumstances, McCandless was poisoned by them, or some substance growing on them.

The seeds are, without a doubt, the most frustrating aspect of the entire affair. It’s oft-reported that over the years Krakauer required three tries to explain the puzzle of the poisonous seeds. As I wrote in 2015, the count was actually four, and is now closer to five:

- The explanation in his original Outside article;

- a modified explanation in Into the Wild;

- a third he offered in 2007 just as the movie was being released;

- a fourth in 2013 for New Yorker;

- and a modified fifth explanation in a peer-reviewed 2015 article, which he also discussed in a 2015 New Yorker article.

Diana Saverin of Outside magazine has a good summation of the history of the questions surrounding the seeds. (This article is also the first and only time I’ve seen a major media source acknowledge that the debate over McCandless’ legacy may be more than a Manichaean battle of “Chris supporters” vs. “Chris haters”: “[Some] readers don’t dismiss McCandless’ intention—spending time in the wilderness—as invalid or stupid. Rather, they reject his endeavor because of the consequence it led to: his death.” While not exactly my position, at least there’s an acknowledgment of a spectrum.)

With Krakauer’s later explanations for the seeds came sympathetic media outlets announcing he’d “solved” the mystery once and for all. NPR has declared the case closed on a couple of occasions. Salon originally titled their 2013 article “Chris McCandless’ death wasn’t his fault” before changing it to the blander “Into the Wild’s twist ending”. (The original title is still there in the page’s URL.)

The Salon switcheroo neatly encapsulates the stakes in play: By declaring McCandless was not culpable for his own death, the lessons and morality people wish to attach to McCandless’ life are preserved. Krakauer’s first explanation paints McCandless as fallible, and perhaps even liable for his own death (that Chris mistook poisonous seeds for edible ones). The later explanations (a mold or bacteria growing on edible seeds) reassures the faithful that McCandless’ death was understandable and unavoidable.

The various poisonous seed theories led to disputes between Krakauer and biologists. Even after the dust settled, the best the scientific minds could declare was “it is possible” the seeds were poisonous and “contributed” to McCandless’ death. That is not the indisputable evidence that some sources reported.

I’ll say it here, just as I said in 2015: I do not think McCandless was an idiot. I do not think he was reckless. He was far more prepared to enter the Alaska interior than a high majority of his admirers who’ve made similar attempts—but he was not prepared enough. I suspect he only realized his mistake when he could no longer trek out of the area (day 69, “river looks impossible”). Unlike living off-the-grid in places like the American Southwest, where he did well, McCandless’ resourcefulness was not enough in a truly remote and brutal location.

But even if rock-solid evidence arrived showing McCandless was poisoned by the potato seeds and nothing more, that does not prove his death was unavoidable. His survival in Alaska hinged on a single food source. He suffered from a single point of failure, and when that point failed, he was doomed. That is not “self-sufficiency.”

The cult

Rosenfield again:

On the 15th anniversary of McCandless’s death, Men’s Journal published a story titled ‘The Cult of Chris McCandless’, an examination of the young man’s legacy in and around the wilderness in which he perished. One gets the sense that there’s still little sympathy amongst Alaskans for McCandless’s death, and the quotes from locals range from pitying to contemptuous.

It’s true: A magazine wrote an article quoting some Alaskans’ contempt for Chris McCandless.

But it’s bewildering that Rosenfield could read the Men’s Journal story and come away with nothing more than the Alaskan angle. It’s titled “The Cult of Chris McCandless” for a reason. The bulk of the article regards the number of people—in particular, young men—inspired by McCandless to enter the wilderness and make a go of it themselves. They are almost always far less prepared for the ordeal than McCandless was when he entered Denali National Park.

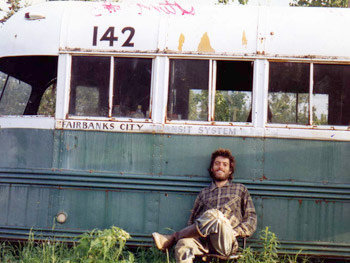

I question the choice of the word “cult,” but confess I cannot offer a better alternative. The obsession with McCandless has made him a kind of secular saint, and the location of his death has become a pilgrimage site. TripAdvisor offers several pages on how to reach it; Google Maps still points to the site of Bus 142 before it was removed by the Alaska Army National Guard to discourage further sightseers. Authorities are routinely called in to rescue lost and stranded hikers. Deaths continue to occur. (Tellingly, Rosenfield mentions the reasons for the bus’ removal without pondering the implications of people losing their lives in the name of “authenticity.”)

If McCandless’ story truly inspires people to learn self-sufficiency—if it leads them to pause and hone the skills necessary to survive in the wilderness—I can only applaud that person for making the vision a reality. But when the inspired believe self-sufficiency is simply a matter of good intentions and a canteen of Evian, there’s a problem.

Compare the evolution of McCandless’ story—the beatification, the successive theories on the seeds, the guarded interpretation of his diary—to Charles Baxter’s observation of a proliferation of “dysfunctional narratives” in America:

Reading begins to be understood as a form of personal therapy or political action. In such an atmosphere, already moralized stories are more comforting than stories in which characters are making complex or unwitting mistakes.

That sounds an awful lot like what happened to Chris McCandless’ story over the span of thirty years.

The politics

Krakauer:

A lot of people came away from reading Into the Wild without grasping why Chris did what he did. Lacking explicit facts, they concluded that he was merely self-absorbed, unforgivably cruel to his parents, mentally ill, suicidal, and/or witless.

Rosenfield picks up where Krakauer leaves off…and makes a serious detour:

The guy who hunts his own food, chops his own wood, and builds his own home, is a suspicious character: a little too trad, a little too in-your-face masculine, probably a Trump voter. And the guy a step beyond that, the one who doesn’t just paint outside the lines but wants to buck the system entirely? There’s something really wrong with him. He’s no pioneer; he’s a misanthrope, a deadbeat, an incel. … We’re afraid of men like this, and we’re afraid of the people who admire them.

This characterization is off-the-rails.

Without exception, criticisms of McCandless as an irresponsible privileged twerp are coded right-wing. The type Rosenfield describes sounds more like a standard-issue take-down of libertarians and hard-right Republicans (“a misanthrope, a deadbeat, an incel”). Those take-downs inevitably come from sources coded as left-wing—the same sources who trumpet McCandless as a modern icon (Salon, NPR, etc.) These sources will question the myth of rugged individualism in American history—and then, with no apparent introspection, hold up high Chris McCandless’ rugged individualism as an example to follow.

If anything, the animus toward Chris McCandless is a mirror-image of the one Rosenfield describes. Critics like to portray him as a coastal elite, a hipster from a privileged enclave who foolishly launched a narcissistic quest for authenticity, and certainly not as a Trump voter. I’ve never heard anyone describe themselves as “fearful” of McCandless’ admirers. “Idiots” is the terse word one acquaintance used when I brought up the subject.

Recall Sherry Simpson: “Mostly I’m puzzled by the way he’s emerged as a hero, a kind of privileged-yet-strangely-dissatisfied-with-his-existence hero.”

“Gather, cook, and eat”

If you still think of me as a “Chris hater,” in return I ask for your opinion of other individualists who forsook modernity and escaped to the wild.

There’s Alastair Bland, the student I wrote about eight years ago. The similarities between Bland and McCandless are remarkable: Both were anthropology majors who believed hunter-gatherer societies were freer and enjoyed more leisure time than agricultural/industrial ones. Both expressed a sharp disdain for modern consumerism and materialism. Bland did not penetrate the Alaska interior, but he did live off the land in and around U.C. Santa Barbara in 2002. Bland found people around him cheering him on:

They marveled at how great [his experiment] was and exclaimed that they would some day try to do something similar. They thought it was a good thing to boycott the American market and a shame more people didn’t appreciate nature’s bounty the way I did.

Like McCandless, Bland wound up concentrating on a single food source—tree figs—which left him bleeding from the mouth and nauseous. His days were spent scrounging for his next meal. He dreamed of climbing trees and eating figs. His life became “gather, cook, and eat.”

Just as McCandless attempted to flee the Alaska interior sooner than planned, Bland too quit his experiment early:

Even now I don’t believe what I did was very constructive. It was a memorable time in my life, to be sure, and it was a good thing to have tried. But to carry on like that forever would have been, for me, social suicide.

There’s Timothy Treadwell who, like McCandless, found a spiritual refuge in the Alaska interior. He lived there for thirteen seasons among the coastal brown bears, both alone and with his girlfriend. Like McCandless, he came from a well-to-do family, and was athletic and gifted. After some failures as an aspiring actor and a bout with alcoholism, he turned his life around. He grew famous for spending time close to the bears in Alaska, daring to approach them to gain their trust. He was immortalized in Werner Herzog’s Grizzly Man.

In October 2003, Treadwell and his girlfriend were attacked and killed by a bear. Treadwell’s running camera captured the audio of the attack. It was the first and only incident of a bear killing a person in the history of Kitmai National Park.

John Rogers of Kitmai Coastal Bears Tour writes of “The Myth of Timothy Treadwell,” although this myth never took on the heroic proportions of McCandless’. While Rogers says, “Timothy Treadwell was not the foolhardy person the media portrays him to be,” he does not acquit him of culpability in his own death, either.

There’s Christopher Thomas Knight, the recluse who lived twenty-seven years in isolation in the north of Maine. In a bit of philosophizing that could have come from McCandless, he said by living alone “I lost my identity. There was no audience, no one to perform for … To put it romantically, I was completely free.”

But Knight survived while habitually breaking into nearby cabins. He was accused of performing over 1,000 burglaries over a quarter-century, pilfering goods and supplies for his own survival.

Note that McCandless has also been accused of breaking-and-entering by Craig Medred:

Three cabins — two privately owned and one a property of the National Park Service — were broken into while McCandless was at the bus. It had never happened before. It has not happened since.

There’s Robert Bogucki, raised in Malibu and a student at Georgetown University. As a young man, he began to question materialism and capitalism. He traveled to Australia to walk solo across its interior desert.

He entered the desert carrying a week’s worth of food and 26 liters of water. When his supplies ran out, he began digging for moisture, and cutting himself to drink his own blood. His absence sparked what was the largest and most expensive manhunt in Australia’s history. After forty-three days, he spelled out “HELP” with rocks and was rescued by a search helicopter. Bogucki “lost more than 30kg [66 pounds] from his 86kg [189 pounds] and it took him a full year to regain his previous strength and stamina.” (McCandless’ corpse weighed 66 pounds—half of Bogucki’s final weight—when he was discovered.)

Why did Bogucki do it? To see God. He desired to model Jesus’ forty days in the desert. He claimed God spoke to him and directed him to water sources. Where McCandless packed in a book on Alaskan horticulture, Bogucki carried a Bible.

Why are these “self-sufficient males” not idolized by the legions of McCandless followers? Why don’t we praise their “sense of adventure”?

Perhaps due to the faulty optics of each story: Bland’s admission of failure in a soft Southern California beach town; Bogucki’s distasteful Bible-thumping; Knight’s “self-reliance” revealed as a reliance on others; Treadwell’s violent attack recorded on tape, supplying us an unromantic record of nature’s grim realities.

Are optics really what makes McCandless different? Doesn’t such a cynical and relativist view smack face-first into McCandless’ values of authenticity—honesty with others, and honesty with one’s self?

It’s taken me nearly a year to write this post. I gave up twice. Researching and writing this has been exhausting. Why spend so much time and energy?

As I wrote in 2015:

Jon Krakauer introduced me to a vivid and lucid life, one that will stay with me for years.

That life has been flattened into an icon, propagated as a cult of personality, and used to buttress petty political divisions. In the least I must register my protest.

Original published November 10, 2014. Significant revisions made on July 15, 2015.

Original published November 10, 2014. Significant revisions made on July 15, 2015.