Original published November 10, 2014. Significant revisions made on July 15, 2015.

Original published November 10, 2014. Significant revisions made on July 15, 2015.

When I learned that Christopher McCandless’ sister Carine had published The Wild Truth, a memoir of growing up with Christopher as well as revelations of abuse within their family, I was surprised at my personal reaction. Many of my feelings I recognized from the time I first read about Christopher over a decade ago. Some of the feelings were new, however—defensive emotions for Christopher, unusual for me regarding a person I’ve never met.

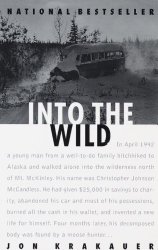

Of course, I did meet Christopher “Alexander Supertramp” McCandless via Jon Krakauer’s bestseller Into the Wild. If Krakauer had published Into the Wild as fiction, he’d be lauded to this day for constructing a sturdy and memorable character, a modern ecotopian Prince Hal whose untimely tragedy stood as a sharp warning to America’s tabloid-driven, go-go 1990s. That Krakauer’s book was based on true events only cemented its standing.

Since its publication over twenty years ago, well-worn copies of Into the Wild have been passed from eager hands to eager hands with the assurance that this is the Baedeker to living an authentic, truthful life. It’s a brilliant read, brilliantly constructed and brilliantly executed. For all the complaints Krakauer has received over the years (he’s often accused of mythologizing McCandless’ exploits), the criticisms would hold no water if the book was a stiff recounting of facts, timetables, and inventories. Christopher bursts off Krakauer’s pages full of vim and vigor, a complicated young man of effusive talents, predictable weaknesses, and eccentric foibles.

I’ve not seen Sean Penn’s film adaptation, but it sounds like he chose to portray McCandless like Christ in the Gospel of John, enlightened and inspired and inspirational—not of this earth. Krakauer, a more evenhanded journalist, knew better. He humanizes McCandless even though he’s obviously intrigued, even infatuated, with the young man. For example, in Into the Wild Krakauer details his own foolish and head-strong solo attempt to climb Alaska’s Devils Thumb. He surely knew doing so he risked criticism of self-indulgence, but the tale perfectly explains by example his affinity for Christopher McCandless.

Into the Wild challenges the reader from beginning to end in all manner of ways. Time and again you must answer a personal question about McCandless: What exactly do I think of this guy? The proof of Into the Wild‘s sturdiness is that you might answer that question a dozen different ways throughout the book.

So, why my own mixed feelings on hearing of a Carine’s new book on her brother? Jon Krakauer introduced me to a vivid and lucid life, one that will stay with me for years. What could trouble me hearing Christopher’s story once again?

Born under a bad sign

Christopher McCandless was born in 1968, making him three years older than me. I have little in common with him otherwise. He was the golden son of a well-to-do family, a star athlete, popular and gifted, a graduate of Emory University with degrees conferred for history and anthropology. I flopped out of high school, technically graduating with a B+ average. Only by the grace of God did I stumble into a good university, then dropped out a year later while enveloped in a smog of marijuana smoke thickened by beer carbonation, much like Pig-Pen in Peanuts walks about in a cloud of grime.

Shortly after dropping out of college, I got in my car and drove. I drove down the California coast all the way to the Mexican border, made the hard decision not to jump across, and then aimed the hood ornament at Las Vegas and hit the gas. Halfway to Vegas, some time around midnight, I pulled off the highway onto a dirt road and cruised a hundred yards into the pitch black Nevada desert. I sat in the dark, the packed dirt of the road freezing my butt, my back against the front tire, and stared out into the darkness trying to figure out…something. Whatever pushed me into the Nevada desert was ineluctable but formless. When I woke up, shivering, I climbed into the backseat and slept a few more hours. The next morning I entered Las Vegas grimy as hell. I had a meal, drove around the city’s downtown, and asked myself what exactly I was doing there. Then I drove back to my rented room in San Luis Obispo.

A few months later, jumpy again and frantic about my life’s direction, I loaded into that same car a cheap tent, a grocery bag of food, some paperbacks, and a Hibachi I borrowed from a friend. I drove north on the winding Highway 1 this time, the endless Pacific yawning out to my left. I ended up at a beach outside of Monterey. I pitched the tent between two sand dunes. The Hibachi proved useless. I had in my haste forgotten to pack charcoal and matches, or for that matter, raw food to cook. I’d also forgotten a sleeping bag, a pillow, or blankets of any kind. A six-pack of beer and a bag of mixed nuts made for a hearty dinner that night.

I have a few more stories like this, but I’ll leave them be. There was a pattern of escape in that stage of my life, one that I recognized immediately while reading Into the Wild. I can’t compare these rather empty and brave-less jaunts to Christopher McCandless’ ruminative journey across the American West and into Alaska’s interior. I was never in any real danger. I was never gone for more than three days. I always had a bank card in my wallet for extra money. I could have called any number of people from a pay phone for help in a moment’s notice.

What I cannot fully explain, even to myself today, is why I undertook any of these manic unannounced departures. They continued until I was about 23, my last one when I was living with a woman and had to explain my way out of it to her when I returned.

What struck me about Krakauer’s book is that he can’t explain why McCandless flew from the good life either. Krakauer tries and tries, even bringing in his own tale about Devils Thumb as way of example, but a lucid explanation is nowhere to be found. It’s not his fault. Without a subject to interview, Krakauer must deduce an awful lot from interviews with McCandless’ acquaintances and the paucity of clues he left behind. But every reader’s first and central question—Why did Christopher flee from his past?—remains unanswered to the last page.

In the forward to Carine McCandless’ The Wild Truth, Krakauer explains he chose not to include details of the familial abuse Christopher suffered to honor the family’s wishes. I respect that. What I don’t respect is Krakauer’s either-or of how readers interpreted this exclusion from Into the Wild:

Many readers did understand this, as it turned out. But many did not. A lot of people came away from reading Into the Wild without grasping why Chris did what he did. Lacking explicit facts, they concluded that he was merely self-absorbed, unforgivably cruel to his parents, mentally ill, suicidal, and/or witless.

I suggest there are other critical interpretations that don’t require dismissing Christopher McCandless in this manner. From Krakauer’s follow-up writings—in Outside and elsewhere—he appears unwilling to entertain those interpretations.

But without this information, readers of Into the Wild form ideas of their own, positive and negative, and most of them clichéd. Impetuous youth—young man seeking Truth—the life of the tramp—even Hemingway-esque man versus nature—all reflect light on McCandless’ bravado but lack true explanatory power. Abuse or McCandless’ disillusionment upon learning of his father’s infidelities, while intriguing, hardly seem like enough jet fuel to carry him from a tony Washington D.C. address to the depths of Denali National Park.

This is why I don’t look upon Carine McCandless’ book with hope. No, I’ve not read it, so don’t view this as a condemnation or even a recommendation against picking it up. It’s just that I suspect her book will be one more attempt to decode Christopher’s psyche as A leading to B leading to C, neatly arranging his motives and back-story the way an English teacher enumerates the salient facts of Hamlet’s situation prior to Act One.

My defensiveness is in earnest. To date, all attempts to explain McCandless’ impulses only reduce him from a human being to a symbol or a metaphor, a grab bag of terminology and ideology.

No, worse: It’s reduced him to two grab bags of ideology.

On one hand, there’s the Authoritative framing. Terms like reckless, irresponsible, and schizophrenic have a comforting effect when applied to someone who steps beyond the norm and suffers for it. Framing Christopher through the authoritative lens leads to summing him up as a head case who stumbled naively into certain doom. That’s why he died in Alaska.

(Haruki Murakami notes a similar framing in Underground: The Tokyo Gas Attack and the Japanese Psyche when he admits to “looking away” from the Aum Shinrikyo cultists because they represented a “distorted image of [the Japanese].” Like Kraukauer, he too has trouble locating their motivations, and it hurts his book. He later admitted the Aum cult was the “black box” of Underground.)

On the other hand, thinking of Sean Penn and the “cult” of Christopher McCandless, there’s the Romantic framing. Web sites memorializing Christopher have sprung up on the Internet, including one (christophermccandless.info) which solicits and publishes essays on how Christopher has changed lives by example. The abandoned bus in Alaska has become a Mecca for young people—in particular, young white men—who brave the bush and snow to visit his death scene. For the followers of Christopher McCandless, terms like enlightenment, questing, and burning desire define and give meaning to his life. Chris was an inquisitive soul seeking truth, beauty, and purity. That’s why he died in Alaska.

If this framing—reckless versus romantic—sounds wearily familiar, it’s because the debate over McCandless’s death has become nothing more than a flash-point in a broader argument we’ve had in America since he and I were born: “The Fifties” versus “The Sixties.” In America those numbers have grown into symbols, binary oppositions of light versus darkness, forward versus backward, good versus evil. I find them frustrating and reductive, but it’s the language we’ve inherited, and so I invoke them.

Seeds, alkaloids, mold, amino acids

While the core question of Christopher’s fate may be Why would he flee? (or, for some, What was he running to?), the factual question that eludes a clean answer is the medical cause of his death. (Nearly half of the Wikipedia article on Into the Wild is devoted to this mystery.) Disappointingly, the contention over McCandless’ legacy—this inane, ceaseless debate of the constrictive Fifties versus the liberated Sixties—has boiled down to chemical analyses of some seeds.

Christopher McCandless in Denali National Park & Preserve, Alaska. His corpse was discovered in the bus he’s resting against here. The bus remains a kind of mecca for Into the Wild devotees.

While living out of a bus in the Alaskan interior, miles from civilization, McCandless subsisted on a diet of squirrel and bird meat, rice he’d packed in, one moose he bagged (but whose meat he failed to preserve), and wild seeds he’d foraged. In his later diary entries he indicated that he believed the potato seeds were killing him, and Krakauer agrees. But how? These seeds had been gathered for thousands of years by indigenous peoples for food, why would they kill him now?

Over twenty years’ time, Krakauer has advanced four—count them, four—theories:

- In his original article for Outside magazine, Krakauer suggested Christopher had misidentified the toxic seed of a wild sweet pea with potato seed. (This is presented as his cause of death in the movie.)

- While writing Into the Wild and with more time to investigate, Krakauer came to believe the potato seed contained swainsonine, an alkaloid that stifles ingestion of nutrients. In other words, Christopher was receiving sufficient calories and nutrition to live, but his bodily processes to absorb those calories had shut down.

- After that had been scientifically ruled out, in 2007, with the movie adaptation about to hit theaters, Krakauer suggested that the seeds McCandless had collected were wet and developed a poisonous mold.

- In a 2013 New Yorker article, Krakauer announced the mystery had been solved: Rather than an alkaloid, the potato seeds contained an amino acid called ODAP which, like the alkaloid of his second theory, caused death by inhibiting ingestion of nutrients.

I don’t blame Krakauer for continuing to puzzle over this mystery. The medical cause of Christopher’s death is the only question of factual importance remaining unanswered. But with Krakauer’s Theory #3 came a whiff of desperation, of someone determined to sustain a favored pet theory no matter what the facts demonstrate. With Theory #4 that whiff became the odor of denial. Theory #4 has been disputed by chemists who’ve tested the seeds for the presence of the amino acid, leaving the question of McCandless’ death once again up for grabs.

There’s quite a bit at stake here. The irresponsible/reckless side of the debate often argue that McCandless’ own ignorance led to his death—not ignorance of toxins, but ignorance of the gauntlet he was undertaking when he struck out across the Alaskan interior. Krakauer’s continued announcements of new answers gives buoyancy to the conviction that McCandless could have continued living his authentic life in Alaska under a more favorable set of circumstances. Who would fault McCandless for failing to recognize an undocumented biotoxin in the wild seeds he was gathering? Ignoring, of course, that no laboratory can detect this poison.

Those on the romantic side of the debate have welcomed each of Krakauer’s new theories as further buttressing to prop up the Legend of Christopher McCandless. For example, Salon’s story on Krakauer’s fourth theory was first headlined “Chris McCandless’ death wasn’t his fault”. Later, Salon revised the headline to “’Into the Wild’s’ twist ending”. The original headline is preserved in the article’s URL. (Headlines are often included in the URL to improve search engine results. Changing the URL later can cause problems, so it remains fixed even if the headline is edited.)

It’s worth pointing out that Outside magazine’s web site no longer hosts Krakauer’s original 1993 article “Death of an Innocent”. Selecting that link redirects to “The Chris McCandless Obsession Problem” by Diana Saverin, dated December 18, 2013. Saverin’s article discusses the legions of McCandless fans who expose themselves to physical harm, and even death, in order to touch and walk within the bus McCandless perished in. It appears Krakauer’s story has been purged from Outside magazine’s web site. Links to it in Saverin’s article return 404 “not found” errors and searching the site locates no usable copy. Saverin’s article is not critical of Krakauer, and it’s difficult to know what to make of Outside‘s missing pages and URL redirection.

(Fortunately, Krakauer’s original 1993 article was reprinted elsewhere, including at The Independent. It was later removed from their site, leading me to now link to a copy stored at the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine.)

“He understood the risks he was taking”

From Carine McCandless’ 2014 interview with Outside magazine:

Because of Chris’s childhood situation, he felt this need to push himself to extremes and prove something. Things came pretty easily to Chris—and by that I mean he was smart and he was good at everything he tried to do—so he had to up the ante a bit and make things harder. Chris believed firmly that if you knew exactly how the adventure was going to turn out, it wasn’t really an adventure. He understood the risks he was taking, and they were calculated, and there was a reason for it.

(Emphasis mine.) This is the crux of my issue with Krakauer’s continued defense of Christopher McCandless. He’s attempting to have it both ways—to claim Christopher was not suicidal, not reckless, and completely in control of the situation, and then claim his death was understandably unavoidable, all in the service of assuring McCandless’ fans that, under slightly different circumstances, Christopher would have fared well in Denali National Park.

But if Krakauer’s perpetually evolving hypothesis is correct, Christopher did not understand the risks he was taking. In engineer-speak, his survival had a single point of failure: He relied too heavily on a single food source, a poisoned source, according to Krakauer. Note that I’m not suggesting McCandless was reckless. Krakauer’s morphing defense of McCandless serves to perpetuate him as a paragon of living a full life. I’m saying the tragedy should be treated as a warning rather than a model.

There’s a fifth theory pursued by filmmaker Ron Lamothe in his documentary Call of the Wild: Chris McCandless starved in Alaska. Not ingested an agent which caused him to stop receiving nutrition, but simply starved due to a lack of available calories. Over the course of 119 days, “despite some success hunting and gathering,” Lamothe theorizes, “McCandless was not able to secure enough food on a daily basis.” It’s so simple it sounds too obvious, but Lamothe makes a strong case with numbers and research from the World Health Organization for support.

Why Krakauer’s and others’ determination to avoid this conclusion? Admission of caloric starvation is admission of defeat in the larger ideological battle. McCandless’ life has been converted into a proxy for this country’s culture wars, a string of battles where no one—no one—raises the white flag. Instead, the soldiers and field marshals and aide-de-camps simply pretend the last loss never occurred and move their attention to another stretch of the battle front. I’m unable to see how this situation honors or respects Christopher McCandless’ life.

“I often felt like a wild animal”

In Christopher’s diaries, he referred to his quests in warlike terms. (“The Climactic Battle To Kill The False Being Within And Victoriously Conclude the Spiritual Revolution!”) Sometimes his plans sound like he’s describing an experiment. Many years ago I learned about another young man who also decided to forgo modernity, to escape civilization, if even for only a few weeks. In the case of this other young man, it was, in fact, an experiment.

In 2002, Alastair Bland, a student at the University of California Santa Barbara, launched what he called “My Project”. For ten weeks he only ate food he gathered in and around Isla Vista, UCSB’s student community. Like McCandless, he opened this experiment full of high hopes. Also like McCandless, Bland was an anthropology student. At UCSB Bland learned hunter-gatherer societies

live freer lives, with more leisure time, than agriculturalists. Twelve to eighteen hours per person per week is all time needed by the famous !Kung people of the Kalahari Desert, for example, to collect all the food they need. This leaves more time for reflection and relaxation than most people in our affluent society ever have—the !Kung don’t need to work to pay rent.

Both Bland’s and McCandless’ rose-tinted exuberance was fueled by a disdain of our modern consumerist society. That disdain was shared by those around Bland:

They marveled at how great [the experiment] was and exclaimed that they would some day try to do something similar. They thought it was a good thing to boycott the American market and a shame more people didn’t appreciate nature’s bounty the way I did.

But Bland’s enthusiasm waned as his experiment progressed:

The people closest to me, more often than not, criticized what I was doing. They said I was becoming weird and that my obsession was taking over my life. They said that I was alienating myself and that all I ever did was gather, cook, and eat…

Even now I don’t believe what I did was very constructive. It was a memorable time in my life, to be sure, and it was a good thing to have tried. But to carry on like that forever would have been, for me, social suicide.

Krakauer stresses throughout Into the Wild and in later writings that McCandless was not in Alaska to commit suicide. I agree. Christopher comes across as too vibrant a personality for that. For him to be suicidal is to believe he was living in a pure manic state for years, hiding or suppressing his depression until his last days in Alaska. But Bland’s term “social suicide” hangs in the air as a remarkable description of what his experiment was truly proving.

I would try to tell myself as consolation that I was somehow perfecting my body and soul, but everywhere and everyday I encountered other people, people smarter and healthier and stronger than I.

The first half of the above sentence could have come straight from Christopher McCandless’ mouth. The second half is nowhere to be found in Into the Wild. And Bland discovers the above while foraging not in Alaska but Southern California, possibly the mildest climate in the Western hemisphere. He foraged along a coastline rife with an incredible variety of edibles, yet Bland’s staple was tree figs because they were the easiest to secure. When he gorged himself on them, they left him nauseous and bleeding from the mouth. Even though Bland didn’t suffer a caloric deficiency (he gained weight during his experiment), he was deteriorating from the inside out.

In Bland’s writings, both in 2003 and later, he comes across as an imperfect Xerox of Christopher McCandless, the toner ink a little less strong, the lines a bit fuzzier, a photostat who survived the journey rather than succumbed to its ordeals. In 2011, Bland’s blog rings of grandiose announcements:

“I was drenched in sweat and rather uncomfortable in the ripping gale that stormed about the mountaintop.”

“A hero’s journey through the Baja badlands in search of a hidden kilo.”

“A Daring Bicycle Ride Through Greece”

While these declarations hold superficial similarity to “Alexander Supertramp” McCandless’ bravado, they are only a surface veneer applied to more quotidian goals. Here Bland enjoys fine wine and craft beer, and he seems unconcerned about surviving off the land. He appears to view nature as a kind of experience to return to in-between necessary bouts of city life. Bland may be described as a bon vivant in the roundest sense of the phrase, one who relishes fresh air as much as he does the bottle of 2007 Pinot Noir he uncorked at the summit of California’s Mount Diablo.

Bland’s 2003 experiment is a vital data point when weighing Christopher McCandless’ fate. Krakauer’s never-ending pursuit to discover new Alaskan biotoxins is an atrophying defense of a way of life Alastair Bland discovered unworkable, an “alienating” “social suicide” that consumed his life. Krakauer and McCandless’ fans hang on to the belief he would have survived Alaska if not for an understandably unavoidable mix-up. They assert that, given a better roll of the dice, McCandless’ battle to “Kill the False Being Within” would have been a clear and decisive victory against modernity, consumerism, and whatever other 1950s ills you wish to conjure up. Bland’s experiment acts as a control to these notions.

Bland concluded his “My Project” experiment eating at a “horrible Mexican restaurant” with his father:

I really felt that I had become a shameless thief and a coward; that I had given up all my self-respect; and that I was going a little crazy, all for the sake of My Project.

Like those who encouraged Bland to keep fighting the good fight (even as he knew what a falsehood his life had become), Krakauer, Sean Penn and too many others are still rooting for Christopher McCandless to win the day—and leading many young people to make harmful, even fatal, decisions.

Maybe it’s time to step back and admit that McCandless’ survival was a matter of him conceding defeat and returning to civilization. That concession doesn’t mean McCandless was reckless or foolhardy. It would’ve indicated growth and maturity. And I suspect he was experiencing just that.

As Krakauer documented from McCandless’ own diary, he attempted to return to society but found himself blocked by a river swollen with snow-melt. I have to wonder if McCandless was not merely starving but also realizing his vision of a pure and authentic life was a one-way ticket.

“Even when full and satiated and liberated from the physical desire for food,” Bland wrote, “I couldn’t relax, I was held captive by thoughts of food. I sometimes dreamed of figs and climbing around in trees.” Is this the authentic life McCandless strove to achieve? His corpse weighed 66 pounds when discovered.

When I drove home from Las Vegas drained and feeling a bit defeated—when Bland took that first bite of his carne asada burrito—that’s the moment in the Hero’s Journey where the hero turns around and retraces the path he cut with his own feet. That’s the Hero’s Journey, dammit, heading home graced with a wisdom one did not originally possess, the journey Chris McCandless failed to take.