I’ve been dipping into Wayne L. Johnson’s 1980 book Ray Bradbury the past couple of months. It’s part of the Recognitions series published by Frederick Ungar, a series featuring critical work on genre writers who’ve transcended their genre.

Johnson’s Ray Bradbury is a biography of the author tracked through his output rather than a stiff-backed recounting of dates and locations of events in his life. Bradbury’s short stories are grouped by subject matter and style as a strategy for analyzing the author’s approach to fiction. Johnson’s book paints a picture of a man who delved deep in the human imagination and returned with some fantastic stories for the ages.

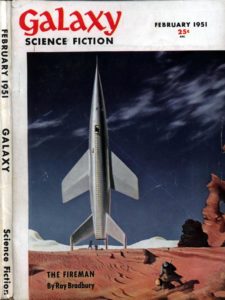

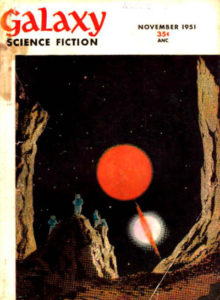

Ray Bradbury was one of the most prolific short story authors of the 20th century because he never abandoned the form, unlike other authors who move on from them to novel writing. Bradbury capitalized on his bounty by disguising his short story collections as longer work (The Martian Chronicles, The Illustrated Man). Even Fahrenheit 451 is itself a maturation of a shorter work first published in Galaxy Magazine.

What caught my eye (and sparked the idea for this blog post) was a brief aside in Johnson’s introduction about how Bradbury was able to sell his prodigious output of short stories across the spectrum of American publishing:

Convinced that most editors were bored with seeing the same sort of material arriving day after day, Bradbury resolved to submit stories which, at least on the face of it, seemed inappropriate to the publication involved. Rather than send “Dandelion Wine” (later a chapter in the novel) to Collier’s or Mademoiselle, therefore, Bradbury sent it to Gourmet, which didn’t publish fiction. It was immediately accepted. “The Kilimanjaro Device” was snapped up by Life, which also didn’t publish fiction, after the story had been rejected by most of the big fiction magazines. … Bradbury insists that he places complete faith in his loves and intuitions to see him through.

Bradbury was certainly a known quantity when these short stories were published but, as Johnson indicates, he still faced his share of rejection slips. I don’t think Bradbury’s wanton submissions were ignorant of market conditions; it sounds to me he was quite savvy with this strategy. (Sending “Dandelion Wine” to Gourmet magazine is kind of genius, actually.) But Bradbury’s strategy transcends the usual mantra to “study the market.”

I’ve been a front-line slush pile reader at a few literary magazines, and I can tell you Bradbury’s intuition is spot-on. When you’re cycling through a stack of manuscripts, they begin to look and read the same. Too many of those short stories were treading familiar paths. Too often they introduced characters awfully similar to the last story from the pile.

A story with some fresh air in it certainly would wake me from my slush-pile stupor. The magazine market has changed dramatically in the past ten years—and absolutely has reinvented itself since Bradbury was publishing “Dandelion Wine”—but I imagine similar dynamics are still in place in the 21st century. Surprise an editor with your story and you just might have a shot at publication.

And if you’re banging out short stories and fruitlessly submitting them one after another to the usual suspects, try taking a risk and following Bradbury’s lead. Trust me, if you can put on your next cover letter that your short fiction was published by Car & Driver or National Geographic, that will surprise editors too.

Recently I picked up Robert Silverberg’s superb Science Fiction 101: Exploring the Craft of Science Fiction, an unfortunate title for a remarkably sturdy book. Part memoir, part writing guide, part anthology, I’d recommend it to every writer whether or not they’re interested in science fiction as a genre or pursuit.

Recently I picked up Robert Silverberg’s superb Science Fiction 101: Exploring the Craft of Science Fiction, an unfortunate title for a remarkably sturdy book. Part memoir, part writing guide, part anthology, I’d recommend it to every writer whether or not they’re interested in science fiction as a genre or pursuit. Science Fiction 101 also reprints thirteen classic science fiction stories from authors like Damon Knight, Philip K. Dick, Robert Scheckly, Vance, Pohl, Aldiss…the table of contents reads like the short list of first-round inductees to The Science Fiction & Fantasy Hall of Fame. Alongside each story, Silverberg comments on why it impressed him and what he gleaned, offering hard, complete examples to his writing wisdom that so many other guides lack.

Science Fiction 101 also reprints thirteen classic science fiction stories from authors like Damon Knight, Philip K. Dick, Robert Scheckly, Vance, Pohl, Aldiss…the table of contents reads like the short list of first-round inductees to The Science Fiction & Fantasy Hall of Fame. Alongside each story, Silverberg comments on why it impressed him and what he gleaned, offering hard, complete examples to his writing wisdom that so many other guides lack. Silverberg’s candor and generosity to the reader is so no-nonsense, he even reprints the rejection notes he received while canvassing science fiction magazines with his early work. Big-name writers usually dip into their rejection stack for the wrong reasons: to settle a score, or thumb their nose at those who stood in their way years past. Here, Silverberg reprints rejection slips that served to make him a better writer, admitting how he deserved them, and how he was often too young to take their advice at face-value.

Silverberg’s candor and generosity to the reader is so no-nonsense, he even reprints the rejection notes he received while canvassing science fiction magazines with his early work. Big-name writers usually dip into their rejection stack for the wrong reasons: to settle a score, or thumb their nose at those who stood in their way years past. Here, Silverberg reprints rejection slips that served to make him a better writer, admitting how he deserved them, and how he was often too young to take their advice at face-value.