See my Introduction for more information about the “Twenty Writers, Twenty Books” project. The current list of reviews and essays may be found at the “Twenty Writers” home page.

Update:

Another interpretation of “The Flitcraft Parable”

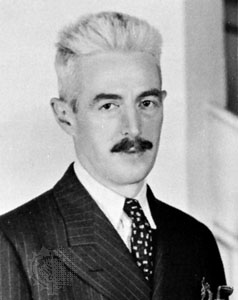

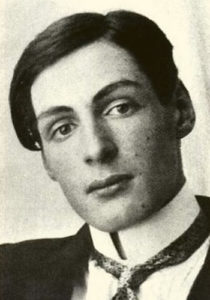

Dashiell Hammett was a prodigious writer, but in the most lopsided kind of way. He wrote north of a hundred short stories in less than five years, grinding out stories every month for an insatiable readership thanks to a plow horse work ethic the pulp magazines of the 1920s and 30s demanded of their writers. In 2011, a researcher going through Hammett’s papers discovered fifteen short stories that had been overlooked, all but lost. There are big-name published authors who’ve not written fifteen short stories in their career. For Dashiell Hammett and his peers in the world of pulps, fifteen short stories was getting your foot in the door.

Dashiell Hammett was a prodigious writer, but in the most lopsided kind of way. He wrote north of a hundred short stories in less than five years, grinding out stories every month for an insatiable readership thanks to a plow horse work ethic the pulp magazines of the 1920s and 30s demanded of their writers. In 2011, a researcher going through Hammett’s papers discovered fifteen short stories that had been overlooked, all but lost. There are big-name published authors who’ve not written fifteen short stories in their career. For Dashiell Hammett and his peers in the world of pulps, fifteen short stories was getting your foot in the door.

It’s striking, then, that after all this output, Hammett was later unable to produce more than five novels, and after those did not produce anything publishable for twenty-five more years, until his death in 1961.

Like his short stories, Hammett’s five novels are of mixed quality and yet all impressive in their staying power. In Red Harvest Hammett created the “man in the middle” genre that directors Kurosawa, Sergio Leone, Walter Hill, and many others would borrow for their own uses. The man-in-the-middle story is a structure Hammett seemingly cut from whole cloth, as no one seems able to point to a true antecedent. Hammett’s genteel, Fitzgeraldean The Thin Man spawned a slew of successful Hollywood pictures. Its form—a fashionable society couple solving murders between martinis and canapés—may sound dated, but judging from the success of Downton Abbey, I bet it could stage a comeback at a moment’s notice. The Glass Key‘s story of a political boss’ right-hand man smashing down rivals rings familiar to any fan of the Coen Brothers’ Miller’s Crossing (although Coen Brothers’ fans should also read James Cain’s mostly-overlooked Love’s Lovely Counterfeit for another important influence). Hammett’s books echo in all manner of 20th century entertainment, here and abroad.

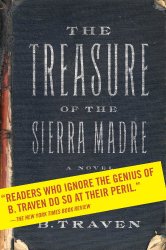

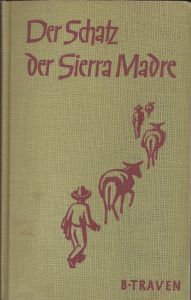

Then there’s The Maltese Falcon, the most widely-known novel in the bunch. Like The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, its title alone is a signifier: fog-soaked San Francisco, the statuette of a solemn stiff-winged black bird, back-alley shootings and mysterious packages arriving by ship from Hong Kong—John Huston knew a great novel when he read it, and he knew better than to monkey with a winning story. If you view the movie immediately after reading the novel, you’ll wonder if there was even a shooting script. Huston’s adaptation hews that closely to the book.

One omission in Huston’s adaptation of The Maltese Falcon is a brief story Sam Spade tells to Brigid O’Shaughnessy, the femme fatale. Spade’s story has nothing to do with finding the Falcon, nothing to do with the motley assortment of characters searching for it up and down the streets of San Francisco, nothing really to do with anything in the novel. The story is a mystery all right, but not in its elements of detection, which it has none of, but what the story means and why Spade is telling it to O’Shaughnessy.

The Maltese Falcon is a model of brisk pacing and efficient writing, a novel of sensation and suspense, and so the digression stands out all the more for it. Spade’s brief tale, two and a half pages long, is one of the most mysterious and puzzling aspects of The Maltese Falcon. Although never referred to as such in the book, it has become known as The Flitcraft Parable.

The parable

Spade tells Brigid O’Shaughnessy of a well-to-do family man in Tacoma, Washington named Flitcraft. In 1922 Flitcraft left his office for lunch and never returned, missing the four o’clock tee-off he’d reserved a mere half-hour before. He also abandoned a good family and $200,000 in the bank, leaving behind no indication of another woman in his life, or any kind of double-life at all. As Spade says about Flitcraft’s disappearance, in what may be the absolute best of Hammett’s prose:

“He went like that,” Spade said, “like a fist when you open your hand.”

Five years after Flitcraft had vanished, Spade was working for one of the larger detective agencies in Seattle when

Mrs. Flitcraft came in and told us somebody had seen a man in Spokane who looked a lot like her husband. I went over there. It was Flitcraft all right. He had been living in Spokane for a couple of years as Charles—that was his first name—Pierce. He had an automobile business…a wife, a baby son, owned his home in a Spokane suburb, and usually got away to play golf after four in the afternoon during the season.

Although not told in-scene, it’s easy to envision Spade’s visit to Flitcraft not so much as a confrontation but a tense social visit. For a tough-guy book, there are no threats or intimidation in The Flitcraft Parable, no car chase or running down dark streets with revolvers unholstered. The parable reads like Flitcraft and Spade were drinking coffee while discussing the situation. But it is tense, as Flitcraft must attempt to explain the logic behind his actions, if any.

After all, what has really changed for Flitcraft? Once again he holds an office job, has a wife and child, a house, even that four o’clock tee-off, all in Spokane, a mere three hundred miles away from a near-identical life in Tacoma.

What precipitated his flight? While going to lunch that day in 1922, Flitcraft passed a high-rise construction site:

“A beam or something fell eight or ten stories down and smacked the sidewalk alongside him. It brushed pretty close to him, but didn’t touch him, though a piece of the sidewalk was chipped off and flew up and hit his cheek. … He felt like somebody has taken the lid off life and let him look at the works.”

Realizing that his life had been randomly spared, Flitcraft decides to randomly upend his life. Like the prince Buddha shedding his family and power and worldly possessions, Flitcraft abandoned his comforts to wander the world. He drifted until he wound up in Spokane, a four-hour drive from his family, and settled into a situation indiscernible from his original:

“He wasn’t sorry for what he had done. It seemed reasonable enough to him. I don’t think he even knew he had settled back naturally into the same groove had jumped out of in Tacoma. But that’s the part of it I always liked. He adjusted himself to beams falling, and then no more of them fell, and he adjusted himself to them not falling.”

The story ends there. Unimpressed, Brigid O’Shaughnessy shrugs off the parable and changes the subject. To the casual reader it appears as a digression from the thrilling search for the Falcon, and not a particularly relevant digression at that. What’s more, Flitcraft’s explanation does not satisfy. There must be more to his story, but Flitcraft is not mentioned again in the novel.

One cannot imagine The Flitcraft Parable finding a place in pulps like Black Mask, magazines that instructed their writers “When in doubt, throw a dead body at ’em.” No gun is leveled, no whiskey is poured, no dame is saved. In The Maltese Falcon Dashiell Hammett crafted the most iconic private detective novel ever, the singular representation of an entire form, and yet in it he wrote the most unorthodox story of detection ever.

Charles Flitcraft

It can be overemphasized that Hammett was, prior to taking up the pen, a private detective. Too often his experience as a Pinkerton agent is treated as a trump card by his proponents, proof that Hammett’s work is authentic compared to the detective fiction of “amateur” hardboiled writers.

It’s important to state: The Maltese Falcon is not a work of hard realism. Hammett understood how to give people what they wanted to read, hence his success in the pages of Black Mask. He also had a preternatural gift of vivid and bold writing. Raymond Chandler asserted Hammett did “over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.” That’s why, unlike most of his peers at Black Mask, Hammett is still studied and marveled over today.

But Hammett was a private eye and he knew the ins and outs of that profession. He knew that such work did not always involve reaching for one’s revolver to get answers. He knew sitting down and talking frankly will sometimes get all the information one requires. No hot lights, no pounding on the desk, no good-cop/bad-cop.

Look again at the subdued language when Spade is hired by Flitcraft’s wife:

Mrs. Flitcraft came in and told us somebody had seen a man in Spokane who looked a lot like her husband. I went over there. It was Flitcraft, all right.

No leggy femme fatale arriving at the detective’s office wearing a mourning veil with a slit up her dress. Mrs. Flitcraft’s entrance has all the dramatic effect of going to the phone company to request a change in service. The weary acknowledgement—”It was Flitcraft, all right”—indicates Spade knew all along it would be the same man, although his reaction later tells us he’d never seen a man skip town for quite the same reasons as Flitcraft’s. The subdued language is echoed in Flitcraft’s tepid attempt to explain those reasons to Spade: “He had never told anybody his story before…He tried now.” This is not a parable of a man making a considered choice. Flitcraft up and left with little self-examination at all, compelled, it seems, by cosmic forces beyond our ken.

Passivity is the standard in The Flitcraft Parable. Even Mrs. Flitcraft shrugs and lets it go when told by Spade of Flitcraft’s bigamy:

“She didn’t want any scandal, and, after the trick he had played on her—the way she looked at it—she didn’t want him. So they were divorced on the quiet and everything was swell all around.”

The parable is built from the elements of scandal and recklessness and infidelity, but like tightening your grip on bread dough, Hammett lets the gooey salaciousness squeeze out and fall away. The three characters—Spade, Flitcraft, and his wife—simply give in to what has happened without complaint or fuss.

It’s not just an usual detective story, it’s an unusual story, no qualifier required. Hammett offers no hero or victim to identify with, no epiphanic moment, and no moral at the end, as most parables would conclude with. The tale has all the trappings of a Cheever story, but it never sneers down on the suburban way of life Flitcraft abandons and returns to. (Keep in mind that Hammett was an urban sophisticate in this period and sympathetic to the Communist Party and socialist movements; he would maintain strong leftist beliefs the rest of his life.) Flitcraft’s escape from domesticity to male freedom also sounds like the setup for an Updike novel, but again, the escape is not truly escape for Flitcraft, just as his return to Spokane is not a return to domestic imprisonment.

For a writer whose stock-and-trade is hot lead and wisecracking gangsters, Hammett tells The Flitcraft Parable with light, oblique touches. One is left with a sense that the falling construction beam shook up the cosmos and dislodged something vital, propelling Flitcraft out into the world. By the time Flitcraft’s orbit returned to domesticity in Spokane, that dislodged piece had slipped back into place and was wedged in tight. The dust settles and little has changed.

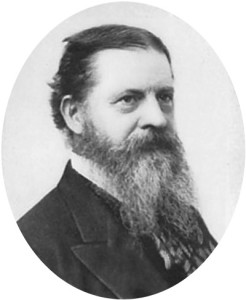

Charles Peirce

An important detail in the parable is Flitcraft’s assumed name when he settles in Spokane: Charles Pierce. This is most likely a reference to the American philosopher and polymath Charles Sanders Peirce (pronounced “purse”), the father of Pragmatism and one of the great thinkers of the 19th century. There is indirect evidence that Hammett knew well of Peirce’s work. In a letter to his publisher, Hammett describes The Maltese Falcon as the most “philosophical” work he’d produced to date. Peirce’s essays were published in popular magazines and his books were widely read and studied. The question then is why Hammett would namedrop one of the most important philosophers of the prior 100 years into a detective story about locating an old statuette.

A clue may lie in Peirce’s work in philosophy. Peirce’s Pragmatism was multifaceted, but one of its concerns was the relationship between doubt, belief, and truth. Peirce was also fascinated with randomness and how it shaped history.

Peirce argued that the universe is not entirely deterministic, that an element of chaos exists, and that this chaos is necessary for variations to form and evolve. He dubbed his theory Tychism. Peirce saw Darwinism as just one example of Tychism at work. Peirce didn’t say that the universe is pure randomness, just that by the injection of a small amount of uncertainty—call it a seed of chaos—variations and change sprung forth, and from there true growth.

Regarding doubt, belief, and truth, Peirce expressed the role of imagination on the search for truth in an 1878 essay he wrote for Popular Science, “How to Make Our Ideas Clear”:

…[Doubt] stimulates the mind to an activity which may be slight or energetic, calm or turbulent. Images pass rapidly through consciousness, one incessantly melting into another, until at last, when all is over—it may be in a fraction of a second, in an hour, or after long years—we find ourselves decided as to how we should act under such circumstances as those which occasioned our hesitation. In other words, we have attained belief.

According to Peirce, doubt is the key component to fruitful inquiry. Not just garden-variety doubt (as in “I doubt I can make it to the party in time”) but the kind of doubt that “stimulates the mind to an activity.” The stimulating doubt forces the mind to engage with the question and come up with an alternative that we believe is the truth. Our decision on how one would act is, in effect, how one did act—”in other words, we have attained belief.”

Putting it all together, the sound of the steel beam hitting the sidewalk, the fleck of concrete striking Flitcraft in the cheek and scarring him (“He rubbed it with his finger—well, affectionately—when he told me about it”), the sudden question of why he had not been killed: This random accident and chance survival introduced a seed of doubt to Flitcraft’s ordered, static life. It caused him to consider an alternate reality—a reality without his family or fortune. When he could imagine his life without them, it was just a few more steps to actualize that idea. Doubt stimulates belief.

Flitcraft’s snap decision seems monumental from our external viewpoint, but for him it was nothing more than a slight shift: “Life could be ended for him at random by a falling beam: he would change his life at random by simply going away.” Flitcraft goes out of his way to point out to Spade the “reasonableness” of his decision. Stepping back, maybe it does seem reasonable. It was also unsustainable—but no matter.

The reason for the telling

While Spade tells the parable, he and O’Shaughnessy are waiting for Joel Cairo to join them. Brigid O’Shaugnessy has had dealings with Cairo in the past and has come to Spade for protection. But O’Shaughnessy has lied to Spade already (in the novel, her first words to him are lies) and he expects her to lie again. This is the commonly offered reason for Spade telling her the parable: Spade is indirectly informing O’Shaughnessy that he does not expect her deceit to end. Like Flitcraft, the thinking goes, she too will not change.

It seems too straightforward a decode for me. Sam Spade is not one for long-winded oratories. It would be much more in character for him to say, “You’ve lied to me before and you’ll lie to me again.” Done and done. In fact, he does tell her that elsewhere in the book. There’s no reason for him to cloak it in a parable about a man in Spokane.

It’s worth noting that Hammett wrote The Maltese Falcon in the third-person objective. Although Sam Spade is in every scene and the narrator stays close to him, we as readers are never privy to Spade’s internal thoughts. We can only guess what Spade is thinking at any moment. That’s the true mystery of The Maltese Falcon, not whodunnit, but What does Sam Spade know, and when does he know it? When it comes to Brigid O’Shaughnessy, I think Sam Spade has her pretty well figured out, much like he knew he would find Flitcraft when he traveled to Spokane. (“It was Flitcraft all right.”) Spade will work with O’Shaughnessy, but only to find the Falcon and to dig out the truth about her…even if that truth confirms what he already suspects.

I also refuse to believe that The Flitcraft Parable is about a man who does not change. Flitcraft’s beliefs are challenged by the chance accident of the falling beam. His travels—his search for some sort of truth—lead him back to his original beliefs. That does not mean his travels were wasted. Flitcraft has no regrets for what he did. His travels—his inquiry—made him a different man, even if he seems to be the same man as before, which he is not.

Spade uses The Flitcraft Parable to issue a statement, a personal credo. He’s saying there is a truth out there and it’s worth looking for it, even if you wind up confirming what you already knew. What’s more, randomness and chance stir the pot, make things happen, creates possibilities. Spade is not Sherlock Holmes. He does not see the world as orderly deductions, one fact leading unquestionably to another. Spade gambles, he take risks, he bluffs. (He’s named after a suit of cards, after all.) Later in the novel an adversary compliments Spade: “There’s never telling what you’ll do or say next, except that it’s bound to be something astonishing.” It’s as concise an observation as any written about Sam Spade.

Charles Sanders Peirce wrote “Do not block the way of inquiry.” Is there a more precise statement of the worldview of Sam Spade? Or, for that matter, the detective novel?

Or of Dashiell Hammett, a man whose left-wing beliefs led to his imprisonment at the age of 55, assigned the duty of cleaning toilets, all for believing that doubt and inquiry could lead to a better society?

November 13, 2015: Check out “Another interpretation of ‘The Flitcraft Parable'”