See the Introduction for more information on “Twenty Writers, Twenty Books.” The current list of writers and books is located at the Continuing Series page.

Peter Bagge is my venerated saint. It took me far too long to figure that out.

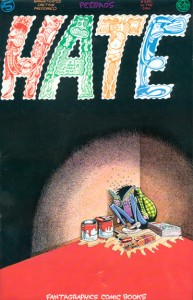

Back in the 1990s, I stumbled across Bagge’s brilliant HATE comics more than a few times—on a comic book store rack, in a cool barber shop’s magazine pile (not that I spent much time at barber shops back then), stuck in the middle of a friend’s stack of High Times back issues, that kind of thing.

Intrigued by Bagge’s manic, skittish covers, I thumbed through these random issues and chuckled over his taffy-stretched characters, all of whom seemed filled with the same gunk they inject into Stretch Armstrong dolls. They flapped their arms in perfect circles as they spewed venom at each other. Their teeth splayed out geometrically toward the reader when they vented or raged about whatever was sticking in their craw at that moment. Then, after achieving a measure of calm, some new perceived outrage would arise on the next page (“perceived” is the key word here) and their tomato would flame up all over again.

In those early encounters with Bagge’s work, I never read an issue of HATE all the way through. I didn’t have to. All the fun was in watching Buddy and his cohorts lose their minds over things most everyone else would find perfectly innocuous or trivial.

And yet…I understood why they would lose it. Yes, I screen my calls, and so do you, so don’t give me that. Yes, I don’t want you drinking from my private beer stash. Yes, don’t tell me you aren’t dating guys and then start dating my roommate. Buddy’s short fuse made perfect sense to me.

At age 32, after a few encounters with Bagge’s work, both in the real world and online, I slowly gathered I’d missed out on something pretty damn important. I began seeking out every HATE issue and collection I could lay my hands on. (By that time, Bagge had quit producing monthly editions of HATE and only released annuals for fans starved to keep up with his incredible pantheon of characters.) Over a two-week reading spree—30 issues, published from 1990 to 2000—I dug into his epic storyline of Buddy Bradley’s clench-fisted life and the miscreants, losers, and delusionals surrounding him. With this closer sequential reading of his work, my heart sank. There was so much more to Bagge’s brilliant decade-long narrative than ranting and arm-flapping. I should have been following HATE as it was published, not lapping it up after the fact.

![]()

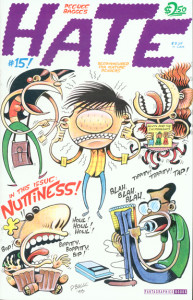

HATE centers on Buddy Bradley, a New Jersey hipster transplanted to Seattle smack in the middle of the grunge era. The early issues circle around the concerns of most any twenty year-old: parties, temp jobs, roommates, looking for sex, looking for authenticity, scrounging for free meals, consuming cheap beer. Buddy’s roommates include paranoiac George Hamilton III and carefree Stinky Brown, one of those guys who manages to get by entirely in the moment and never lacks a girl on his arm. The elliptical orbit of Buddy’s love life has two foci: unstable, abortion-prone Lisa and uptown girl Valerie.

Buddy manages to eke his way through Seattle’s grunge scene (and later, suburban New Jersey) through a combination of entrepreneurship, conning favors from friends and strangers, shoplifting, and mostly-idle threats. Although HATE‘s early issues delve deep into college life sans actual college enrollment, something less remarked upon is the tension in later issues when Buddy swears it’s time to shape-up and grow-up, moving back to New Jersey to settle down with Lisa in his parents’ basement.

Doonesbury‘s Yale hippies and commune malcontents progressed into adulthood in the 1980s, but their outlook (i.e. their politics) shifted not one iota—thankfully, otherwise they might have had to live up to the judgy pronouncements they’d decreed a decade earlier. In the final monthly issues of HATE, the New Jersey Buddy Bradley is but an echo of his Seattle predecessor. He’s like that college pal who swears off pot, buys a tie, and obtains a business loan to start selling water bongs mail-order. What a square.

![]()

I do not see myself as a live-in-the-flesh Buddy Bradley, but there is much of him I recognize in myself. His firebrand rant about hating rock ‘n’ roll is one I’d preached as well (almost down to the word) to a San Luis Obispo house full of Generation X hippies. (They never invited me back.) And while I never had a roommate like George Hamilton III, I kinda-sorta resembled him due to my Robert Anton Wilson-inspired pet theories about secret power structures and hidden knowledge. And Buddy drinks Johnnie Walker Red Label. Eerie! (I could go on.) When I reached age 32, I thought I’d been through something unique—as unique as a crushed Coke can, HATE informed me.

Bagge’s genius as a storyteller reflects one of my personal peeves about contemporary fiction—”the cult of poignancy” as editor David Holler dubbed it. That is, the urgent desire of literary fiction to land in a moment of soft, still self-reflection. This desire is simply a rejiggering of Hollywood’s desperate need to reach a concluding morality that assures us there is Good in this world, and genre fiction’s love of pat, satisfying endings.

HATE eschews closing any story with revelation or insight into Buddy’s life, or even a resolution you would call “a resolution.” There’s rarely any forward momentum at all. In almost every issue, Buddy winds up pretty much where he started, albeit bruised or unconscious or a bit richer or poorer for the journey. HATE isn’t anti-poignant, as that suggests Bagge was consciously working against easy pathos. HATE is merely absent of poignancy, or any moral compass for that matter. Buddy Bradley is a vector of force propelled by the rocket fuel of disgust, outrage, and self-interest—and yet Bagge maintains our sympathy for him. Our sympathy for Buddy Bradley parallels our sympathy for Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost. We recognize too much of ourselves in them both to toss them overboard.

But that sympathy is never comfortable. There’s an unsettling randomness to the consequences of Buddy’s antisocial decisions. There is no divine thumb on the cosmic scales in HATE. There aren’t even scales. When Buddy screws over a roommate or a girlfriend and comes out ahead free-and-clear, his brash grin for the reader is disturbingly celebratory. Buddy is bragging to us, “I got away with it.” And Bagge, the author, never steps in with a value judgment.

Many writers claim they write amoral or morality-free stories, but few writers have truly shorn our Western value system. Even Seinfeld had a karmic ethos of deserved and undeserved comeuppance. Whether Buddy’s unscrupulous world-view and self-centered priorities are the symptom or the disease—or the cure—I leave that question to others. But I’ll take Buddy’s value system over Holden Caulfield’s cap-wringing and Tyler Durden’s under-microwaved existentialism every time.

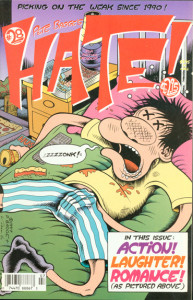

![]()

For all the praise Bagge’s received for documenting the grunge era in Seattle, I say Bagge actually recorded something more important. HATE performs an X-ray on an oft-overlooked segment of the American population, the suburban-bred young adults who didn’t power through college and upward into the American workforce. Nor did they coast into the coastal creative classes thanks to a grandmother’s trust fund or their partner’s cushy income stream. They’re educated and savvy enough to hold down service work and low-paying professional jobs without falling backwards into poverty, the supposed only possible outcome in the traditional left-wing scripts handed down to us. They discovered early on that getting ahead in America is a far more vicious enterprise than it should be. They quit pretending upward mobility is even a worthy goal. Instead, they relented to a daily grind of work, alcohol, sex, and hate.

I’m not playing a violin for these folks. Neither is Peter Bagge. That’s kind of my whole point.

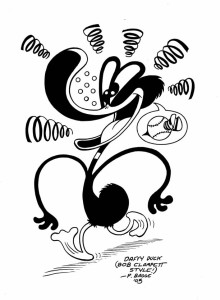

Now an admission: When I was 20 I resembled this guy more than any single figure in Bagge’s epic:

A good (and free) introduction to Bagge’s narrative and artistic style is “The Hasty Smear of My Smile”, an alternate history of postwar America and one of my favorite standalone strips he’s put together. Koo-koo-ka-choo.