When I started this blog years ago, I made a private agreement with myself: I would avoid writing topical political content. Substack, social media, and the blogosphere is saturated with political commentary, providing lots of heat but little light. I don’t like trafficking in outrage, which is the fast-track to success in political blogging.

However, I did write a novel about missile defense set during the Reagan Era in a town hosting a nuclear weapons research laboratory. That’s pretty political, even if the politics are fairly retro.

Due to recent events in the Middle East, the topic of missile defense has come up again, primarily thanks to Noah Smith’s Noahpinions (via). Smith’s piece on recent successes in missile defense tickled a nerve in me, mostly because this is a topic I’ve followed off-and-on for forty years.

To clarify, while my book is tinged with autobiography (I did indeed grow up in Livermore during the Reagan Era while the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was being developed), it’s also fiction (neither of my parents worked for Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), although almost all my friends’ fathers were scientists there).

This is why I reacted strongly to Noah Smith writing this:

…for most of my adult life, I believed that ballistic missile defense was a hopeless, failed cause. From the 2000s all the way through the 2010s, I read lots of op-eds about how kinetic interceptors — “hitting a bullet with a bullet” were just an unworkably difficult technology, and how the U.S. shouldn’t waste our time and money on developing this sort of system.

He quickly adds,

Even the most ardent supporters of missile defense don’t think it could stop a nuclear strike by Russia or China. … critics of missile defense were right that missile defense will probably not provide us with an invincible anti-nuclear umbrella anytime soon. But they were wrong about much else.

Fair enough—Smith is differentiating between defense technology for stopping short- and medium-range ballistic missiles armed with conventional explosives (such as the type used to protect Israel from Iran’s attack in April) versus technology for stopping long-range nuclear ICBMs, which was the problem SDI was supposed to solve. Over the last forty years critics of missile defense have muddied these categories, taking the problems of developing an ICBM defense system, which must deal with missiles launched into the upper atmosphere, and translating them to conventional missiles, which fly at altitudes similar to prop planes.

With this proviso out of the way, Smith goes on to argue that “the way in which critics got this issue wrong illustrates why it’s difficult to get good information about military technology — and therefore why it’s hard for the public to make smart, well-informed choices about defense spending.” He proceeds into the history of short- and medium-range missile defense and its uninformed and myopic critics. It’s a thoughtful piece, well-reasoned and well-researched.

What’s my beef, then? It’s his assertion that the critics getting their prognostications wrong make it “hard for the public to make smart, well-informed choices about defense spending.” I disagree.

What I saw during the SDI years, and continue to see in 2024, is a dearth of public involvement in defense spending or development. How can the American public make well-informed choices, given the lack of transparency in budgeting or the research process?

This is not a bleeding-heart appeal (such as the 1980s bumper stickers Smith references: “It will be a great day when our schools get all the money they need and the Air Force has to hold a bake sale to buy a bomber”). Simply put, the public is not informed on the decision-making process, has not been invited into the process, and is not wanted to be involved in the process.

The evidence for this is in the history of missile defense itself. Even with four decades of critics piling on against it (which Smith thoroughly tallies), the short- and medium-ranged missile defense technology they mocked was approved, funded, developed, honed, and deployed. As far as I can tell, no one was voted out of office for supporting missile defense. No referendum on their development or funding was held.

Smith theorizes that with missile defense,

the information about how good America’s weapons systems are gets kept behind closed doors, unveiled in secret Congressional briefings and whispered between defense contractors. Meanwhile, everyone who wants to criticize U.S. weapons systems is on the outside, squawking loudly to the press.

My skepticism originates from Smith’s belief that the problem is an “asymmetry” between the military, which is secretive “in order to avoid alerting America’s rivals to our true strength,” and mouthy critics of short- and mid-range missile defense, which have a poor track record for predicting its failure.

Now, Smith’s point is a defensible perspective. It’s equally defensible that the reason the military is so hush-hush about their research projects is to keep the American public in the dark. When defense budgeting is discussed publicly, it’s about funding for more bread-and-butter expenses, such as better meal rations and outfitting soldiers with body armor. Who’s going to argue with supporting our troops?

In the 1980s, the public was well aware of the SDI project. It was highly publicized. Reagan announced it on national evening television. What the public did not know was how the LLNL planned to stop those nuclear missiles from reaching American soil. One of the earliest approaches they explored was a theoretical X-ray laser fired from orbiting satellites at the incoming missiles.

(Defenders of ICBM missile defense point out that the X-ray laser was merely one of many approaches considered. That’s true, but it’s also true that it, and so many of the other technologies considered, were discarded as impractical, unworkable, or simply dangerous. The history of SDI and its offshoot Brilliant Pebbles goes into the many misses and problems.)

To return to the X-ray laser: How was it to be powered? The proposal was that each satellite would hold a thermonuclear device. To fire the laser, the internal device would detonate. The contained thermonuclear explosion would shed X-ray radiation, which was redirected toward the intended target.

It’s easy to satirize this proposal (which I certainly did) as though a plot point in a hypothetical Dr. Strangelove sequel. My point here isn’t to knock research that sounds ludicrous, or which didn’t pan out during development. The history of technology, science, and engineering is littered with wild ideas and failed approaches.

My point is: SDI was highly publicized, but the energy source of the X-ray laser wasn’t revealed until years later by a whistleblower. The public could not make an informed decision, because the most vital information about the project was being withheld. Was it withheld because the U.S. military didn’t want to tip its hand to its enemies? Or because the details would be tremendously embarrassing—H-bombs in space to defend America from H-bombs in the sky? I lean toward the latter explanation.

How many voters today are aware that anti-ICBM research is still ongoing in 2024? The SDI project was renamed multiple times over the decades, as a cynical way to sneak it through the budgeting process. It was never defunded, although, again, as Smith and others recognize, “even the most ardent supporters of missile defense don’t think it could stop a nuclear strike by Russia or China.”

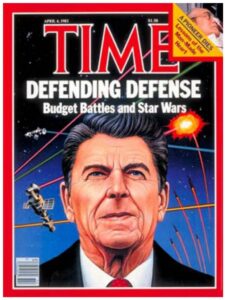

Rather, I think the military learned a lesson from Reagan and SDI: Don’t tell the public about your darlings. From a perspective of secure funding, there’s more harm than good from having your pet research project on the cover of Time.

To be fair, Smith doesn’t advocate for giving the U.S. military carte blanche on spending and research: “There’s no easy solution here, other than simply being aware of these difficulties and trying very hard to counteract them. We pundits should talk to and listen to a variety of experts, not just the loudest and most confident.” I agree, although I think his advice should extend well beyond the sphere of the punditry.

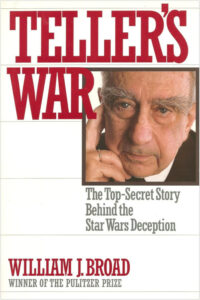

And Smith’s also right about the poor track records of critics of conventional missile defense. In the case of SDI, though, the polarity is reversed. Journalist William Broad’s first book on ICBM missile defense, Star Warriors, was a hagiography of SDI and the scientists at LLNL. From the tone and tenor of the 1985 book, a reader might think ICBM defense was simply a matter of getting the brightest and best minds together in a room with a whiteboard and a pot of hot coffee.

Broad’s later account, 1992’s Teller’s War, tells a very different story, revealing not only the research failures, but more critically the deceptions, exaggerations, and maneuverings used to sell the project to Reagan, Congress, and the American public. Broad barely references his earlier Star Warriors in the later book. In fact, reading between the lines of Teller’s War, its tone comes across a little like a scorned partner who realizes far too late that their spouse had baldly lied to them about an infidelity years earlier.

A postscript. When I wrote “the public is not informed on the decision-making process, has not been invited into the process, and is not wanted to be involved in the process,” that largely assumes the public wants to be informed about defense budgeting.

In an era of political gamesmanship, where “owning” the other political team is more than important than actual leadership and problem-solving, I’ve seen very little interest from the public in how our defense dollars are being spent. Perhaps the military doesn’t need to be secretive at all any more about its research projects.