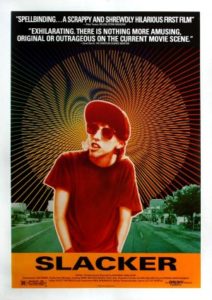

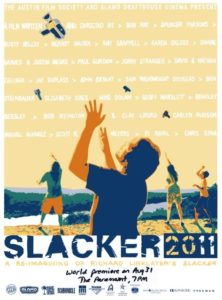

Although I can’t imagine any of the characters in the film Slacker being terribly nostalgic about anything, it’s worth noting this year marks the 25th anniversary of the release of Richard Linklater’s gem. Sanctified in The Onion A.V. Club’s “New Cult Canon” and topping numerous critics’ “best indie film of all-time” rankings, Slacker is an odd addition to any best-of list. After all, this is seemingly a film about not giving a shit.

At least, that’s the most immediate impression on first watching Slacker and its nontraditional film narrative. Slacker doesn’t follow a story arc of one or two characters, and it’s not a collection of marginally intertwined stories like Altman’s Short Cuts or the animated Heavy Metal. In Slacker the camera floats from one group of people to the next, eavesdropping for a minute here or ten minutes there, taking snapshots of the lives of tens of people connected only by the slenderest of threads—in sum, documenting a day in the life of Austin, Texas, circa 1991. Often these moments have no distinguishable beginning or ending, just slices of time in the company of cafe philosophers, conspiracy theorists, guys trying to get laid, and girls trying to be taken seriously. Like I said: It has the attention span of someone who doesn’t give a shit.

Entirely linear, Slacker never flashes back or forward, always remaining in the moment, giving the film a kind of bald, unprotected sensation. The camera drops into discussions midstream. We have the opportunity to watch and listen but the film leaves it entirely for us to surmise backstories and histories. Then, as one or two people in the group grow fidgety or distracted—or bored—they move on, as does the camera, riding along with them to the next interaction. There’s no soundtrack to speak of, only the occasional background music from a radio or club band. The camera is the star of Slacker. It took me years to realize it.

The film opens with a young man (director Linklater himself) arriving in Austin. He launches into a chain of free-form ruminations on a dream he had the night before while the uninterested taxi driver drives him into town. (The dream is a wispy summary of the movie to follow, but most viewers will miss that, even after repeating viewings.) The film closes with a raucous group of friends driving a convertible to the mountains outside of town and, in a final pique, throwing the camera—the star of the movie—down a cliff. In between, the camera moves between perhaps fifty different vignettes, eavesdropping on everything from the inane and mundane to the fantastical and bizarre.

Impossibly, each of these moments is wonderful in its own right. Some of the episodes reach farther than the others. Everyone who’s watched Slacker remembers its most famous scene, the overly-familiar young woman (Teresa Taylor, drummer for the Butthole Surfers!) fencing a stolen jar containing Madonna’s pap smear, pubic hair and all. My personal favorite remains the inept burglar caught in the act in an elderly bohemian’s house, only to receive a gentle education on the history of anarchism in America. It’s the most complete and well-rounded episode in the film, a luxurious Carveresque vignette with a beginning, a middle, and an end that is unlike every other vignette in the film. It comes near the midpoint, giving the audience a kind of narrative breather before Linklater’s tour of Austin’s alt-underground bestiary continues.

Considering its unconventional narrative style, Slacker is refreshingly unself-conscious (and unself-congratulatory) in its rule-breaking. (The opening with Linklater in the cab may be the only “meta” moment in the film.) For all the rules this self-financed film breaks, it’s comfortable and comforting viewing, the absolute opposite of the avant garde. That’s another reason Slacker sustains after twenty-five years. It’s hard to mock a film-school film and its no-name cast when it’s so relaxed in its own skin.

Any review or retrospective of Slacker is bound to name-drop “Generation X,” and I won’t disappoint on that count. (After all, I’ve got some skin in the game.) Slacker is often called the definitive film of my generation. But when I think of the “great” movies of a generation—Easy Rider and The Big Chill for the Baby Boomers, The Social Network for the Millennials—I see yellowing, curling Polaroids losing their currency with each passing minute; movies of like-aged, like-minded, similarly-groomed people bellyaching they’ve not gotten their due. Slacker is not that film.

Critics sometimes make hay that this is not truly a Generation X film because not every character is of that age. It’s true, but it’s also true the older characters are treated more reverentially than the Gen-X hipsters and artists and kooks. In films like Easy Rider and The Social Network, the older generation is sniffed at with disdain and suspicion. In Slacker, those suspicions are reversed. An age-worn hitchhiker and the anarchist mentioned before are voices afforded the opportunity to air their wisdom to a welcome audience, while the specious logics of the younger generation are treated as clever amusements. In the film’s final moments, an elderly man strolls down a street narrating into a tape recorder the quiet poetic wisdom of a long, full life—only to be interrupted by a young man, 20 or 21, driving an electioneering truck with mounted loudspeakers blaring empty rage about guns and knives solving all political problems. It’s obvious where this film’s sympathies lie. It’s also why this film truly is the definitive Generation X movie: We’re so suspicious of inauthenticity and hollow idealism, we don’t even trust ourselves. We don’t even trust our distrust.

For the A.V. Club’s “New Cult Canon” review, Scott Tobias puts his finger on why Slacker is distinguished from other generation-defining movies:

It isn’t enough to think of Gen-Xers as merely jaded and sarcastic; indeed, there’s little of that attitude on display in Linklater’s film. But there is a sense of profound disconnection, a refusal by young people to participate in a system that will bring them no joy and wither their souls. As one character puts it, “Every single commodity you produce is a piece of your own death.”

My personal introduction to Slacker was in 1992, not long after its release, watching the movie on VHS at a Saturday night pasta feed. Eight or nine of us were crowded into a San Luis Obispo duplex living room, me and my college-aged friends, some I knew well, some only slightly. In particular, the singer and rhythm guitarist of my band was there. (We were going to be big, but no one understood what our music was doing.) We feasted on plates of red-sauce spaghetti and hot garlic bread. One of the women had made her easy-bake Apple Brown Betty. Others brought ice cream and red wine and bottles of the local beer. Dinner and a movie, on the cheap.

The singer was engaged to marry one of women there, the Brown Betty baker who was a housemate of mine. I was becoming involved with another woman in the room, a second housemate of mine that I would go on to live with for thirteen years. There were likely other sub-plots in that room I was unaware of. We were all young and about to grow old.

We knew, collectively and subconsciously, we were about to be dropped on a high-speed conveyor belt and told to run as fast as we could to keep up. “Getting ahead” sounded an awful lot like “falling behind” to our ears. Some of the people in that room thought they could step off the belt and steer clear of the inevitable. The rest of us knew, it’s called inevitable for a reason. We were resigned to what was coming, and resigned to it in our own ways.

That’s why Linklater’s cafe au lait Dostoevskys and tin-foil hat savants engage twenty-five years later. The game for the viewer is not teasing apart thought-provoking insights or brilliant dissections of American culture. Most of the musings in Slacker are, in fact, well-adorned horseshit. The game is piecing together how reasonably-educated people would arrive at such philosophies—and everyone in this film has their own philosophy, make no mistake. There’s a postmodern dignity that comes with assembling a personal credo from piece-parts and staying true to it, no matter how whacked-out it may be. And that’s what’s going on in this film, with zero irony and zero sarcasm.

Pre-Internet and pre-Seinfeld, Slacker appears to be a grungy sun-drenched film of a drearier, less-snarky age. I say Linklater offers blueprints for an examined life—not the examined life, but examples of them. This is an earnest film of multiplicity and pluralities. With few exceptions, the characters in Slacker withhold judgment of each other. They give each other the benefit of the doubt. Even when it’s obvious one of them is babbling nonsense from out in the weeds—”We’ve been on the moon since the ’50s!”—the other characters give them their space. There’s a moment in the film where a character takes a swipe at Texas Libertarians. It seems to me that Slacker‘s code of live-and-let-live stands not far off.

Most critics pick up on a line uttered late in the film: “Withdrawing in disgust is not the same thing as apathy.” It’s often interpreted as the film announcing its own thesis statement, possibly the only other “meta” moment. It’s worth taking a closer look.

I don’t see a lot of disgust in Slacker. There’s a bit of it sprinkled around: the roustabout hitchhiker (“I may live badly, but at least I don’t have to work to do it”), a mouthy “anti-artist” berating a hipster at two in the morning, the enraged polemicist in an old-fashioned electioneering sound truck. That may be about it in the disgust department, though.

Listening to the director’s commentary recorded for Slacker‘s 20th anniversary, I gather Linklater’s not terribly interested in elevating emotions like disgust, rage, vengeance, or hatred. His anecdotes regarding Slacker are soft recollections of easier days: a buddy who came through with film equipment, good times working in a T-shirt shop, an ex-girlfriend actor he’s still friends with, that sort of thing. Slacker is a Baedeker for a particular way of life. Sleeping on couches, trips to dusty used-books stores, pick-up games of Ultimate, the quest for the best burrito—any town with a robust college or arts school has this scene. For people living this life, Slacker is a documentary.

Returning to that immortal line—”Withdrawing in disgust is not the same thing as apathy”—I don’t even think there’s much apathy in the film, at least in its purest form. Shrugging off others’ pet theories or forgoing a work ethic is not apathy. Questioning whether ex-convicts should be denied the right to vote, or wondering if the media used Smurfs to inculcate America’s youth—both voiced in the film—doesn’t strike me as apathetic either.

Withdrawal, however, is definitely the common filament of Slacker, the third rail powering the camera’s dolly as it journeys across Austin. The closest Slacker gets to engagement is a gung-ho “cultural terrorist” selling T-shirts on the street. Slacker‘s characters don’t merely question, they question the act of questioning. The film seemingly about not giving a shit is more subversive than most people think.

What did E. M. Forster write in Howards End? “Only connect”? Slacker is “only connect” put to film.

Twenty-five years on, I’ve lost touch with the folks in that San Luis Obispo duplex discussing Slacker‘s dynamics over glasses of red wine. Over the years I intersected with a few of them, connecting briefly before moving on.

I’ll be bold and surmise that back then, laughing and marveling over Linklater’s creation, none of us wanted to leave San Luis Obispo. We didn’t even want to leave that room. Perhaps some of us never truly left it behind.

I suppose that’s why I rewatch Slacker every few years, just as I reread certain books which have deeply affected me. Rewatching Slacker is reconnecting with a past and making it a present, even if only for a moment. It keeps alive within me a little bit of that necessary withdrawal. It reminds me to only connect.