James Ellroy’s brilliant novel L.A. Confidential introduces readers to Sid Hudgens, one of Ellroy’s most colorful and enduring characters. Publisher of Hush-Hush magazine (“off the record, on the Q.T. and very hush-hush”), Hudgens gleefully reports on the secret lives of drag queens and lesbians, dishes the dirt on the famous (Robert Mitchum’s “Big Dope Bust of 1948”), and outs hunky actors whenever the whiff of non-heterosexual possibilities are sniffed out by him and his camera lens.

While Gawker Media weathered the storm this week over its outing of a Condé Nast executive embroiled in blackmail, I found myself revisiting Ellroy’s Sid Hudgens and all that Hudgens represents. I’m enjoying the Gawker circus immensely, delighted by each day’s revelations (Gawker “in a total meltdown”, “editors resign over flap”, Gawker to be “20% nicer”). Now this is my kind of tabloid journalism!

And I’m not the only one. I’ve noticed a preponderance of the word “schadenfreude” in accounts of Gawker’s self-induced implosion. (I even coined a neologism for the phenomena: gawkenfreude.)

I admit, I’m not entirely elated with Gawker Media’s and CEO Nick Denton’s funky little mess. I’m a fan of io9, a Gawker Media venture that avoids the lurid and sensational. In their place, io9 emphasizes reliable, thoughtful pieces for the science and science-fiction crowd. It’s also one of the few mainstream media sites to treat ebooks and self-publishing with the dignity they deserve. io9’s writing is remarkably free of the snark that Gawker churns out like dollar-mart peanut butter. (I should mention that I’ve socialized with io9 editor-in-chief Charlie Jane Anders in the distant past.) But io9’s good work isn’t enough to stop me from gawking at the Gawker pile-up.

With all the schadenfreude over the train wreck that is Gawker Media, maybe it’s time to acknowledge the immense debt Nick Denton & Co. owe to the Sid Hudgenses of the bygone tabloid era, 1940s and onward.

James Ellroy’s creation is most likely an amalgamation of two historical figures, Myron Fass and Robert Harrison. Media impresario Myron Fass revived the Eisenhower era Hush-Hush News in the late 1960s. In addition, he published “up to fifty titles a month, many of them one-offs, covering any subject matter he thought would sell, from soft-core pornography to professional wrestling, UFOs to punk rock, horror films to firearm magazines.”

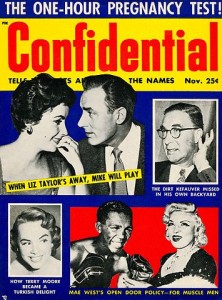

Robert Harrison published Confidential magazine in the 1950s, whose editorial style was “laden with elaborate, pun-inflected alliteration and allowed stories to suggest, rather than state, the existence of scandal.” Those pun-laden alliterations became Sid Hudgen’s calling card in both L.A. Confidential and later stories featuring him. (You can hear Hudgens’ pleased hiss as he says “sinnnn-sational.”) When Hudgens narrates a story in this alliterative fashion, Ellroy’s prose becomes a thick, near-unreadable Finnegan’s Wake of double entendres, word mangling, linguistic winks and nudges, and postwar film references.

Myron Fass represents the more lurid of the two—his love of the grotesque, bizarre, and outlandish comes through in his wild covers. Harrison’s Confidential was more conservative in both subject matter and politics, taking the pose of a moral crusader exposing those in power and delivering the truth to a deserving public.

Danny DeVito as Sid Hudgens, L.A. Confidential

Curtis Hanson’s film adaptation of L.A. Confidential did a damn fine job boiling Ellroy’s tangled ride and entwined characters down to a focused, seasoned narrative. Screenwriter Brian Hegeland developed brilliant scenes that establish complicated characters onscreen in moments. Here’s Sid Hudgens (impeccably played by Danny DeVito) explaining his vision of…the future:

Jack Vincennes: It’s felony possession of marijuana.

Sid Hudgens: Actually, it’s circulation 36,000 and climbing. There’s no telling where this will go. Radio, television. Once you whet the public’s appetite for the truth, the sky’s the limit.

Compare Sid’s ambitions to Nick Denton’s pseudo-manifesto of Gawker’s values:

“We put truths on the internet.” That has been the longstanding position of Gawker journalists. … It is not enough for [stories] simply to be true. They have to reveal something meaningful. They have to be true and interesting.

I won’t quibble with “interesting” except to point out that this is the word choice of a one-time journalist and editor.

“True,” however, is worth pondering. Nick Denton is not invoking the philosophical notion of truth as handed down to us from Aristotle, Sartre, Kant, and so forth. This is a schoolyard notion of truth, or rather, The Truth. A bottled, constrained substance, the prim and scolding schoolchild feels entitled and duty-bound to uncork The Truth and dump it out into the sandbox and onto the heads of their peers, damn the consequences—to others, of course, never him or herself. “True and interesting,” as airtight and ironclad a journalistic ethic as any, Sid Hudgens might say.

While Gawker‘s writers talk up the First Amendment, firewalls between business and journalism staff, and the purity of The Truth they seek to release, it remains that the core of Gawker‘s pulled story lies an attempt to out a man as gay. In Gawker‘s 1950s worldview, homosexuality remains an accusation to deny or confess to. Even when Gawker’s writers insist staying in the closet is a form homophobia, their devotion to exposing “true and interesting” homosexuality rings as hollow as Sid Hudgens’. Gawker and Hudgens see it as their personal duty to pull back the curtain on private lives whose personal choices—right or wrong—have zero impact on the public.

And Gawker has been relentless in their crusade of outing public figures (never mind the question of whether the Condé Nast executive is a public figure). Look no further than their perverse, sordid, multi-year quest not only to out James Franco as gay, but as a gay rapist—a charge they determined by counting the yea and nay votes in their readers’ comment section. Outing gay men (accurately or inaccurately) is the staple crop of tabloid journalism’s output and the raison d’être for its existence. In other words, Gawker is not the innovator it presents itself as. Gawker has an unsavory, weathered provenance that goes all the way back to the days of Myron Fass and Robert Harrison.

Tabloid journalism does not engage. It shames, it derides, it scorns, it scolds. It’s the clucked tongue put to print. It’s the transcription of knuckles rapped in delight. By refusing to engage in the substance of a story, Gawker‘s revered snarkiness is revealed as nothing more than Sid Hudgens’ pit-bull taste for lasciviousness, but more hipster and less hepcat.

Still, I can’t help but feel Sid Hudgens won. He foresaw the future with more clarity than Arthur C. Clarke or Isaac Asimov. From four-color tattler rags to Walter Winchell’s radio gossip to checkout line National Enquirer to prime time’s A Current Affair to the O.J. Simpson trial circus to Gawker Media’s empire—Sid Hudgens, Myron Fass, and Robert Harrison built the future one rumor at a time. Whet the public’s appetite for The Truth, boy-o, and the sky’s the limit.