In John Updike’s Picked-up Pieces, he expounds on his personal rules for reviewing books. I’m quoting them here to remind myself of this hard-won wisdom as well as to share with others:

- Try to understand what the author wished to do, and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt.

- Give enough direct quotation—at least one extended passage—of the book’s prose so the review’s reader can form his own impression, can get his own taste.

- Confirm your description of the book with quotation from the book, if only phrase-long, rather than proceeding by fuzzy précis.

- Go easy on plot summary, and do not give away the ending.…

- If the book is judged deficient, cite a successful example along the same lines, from the author’s oeuvre or elsewhere. Try to understand the failure. Sure it’s his and not yours?

To these concrete five might be added a vaguer sixth, having to do with maintaining a chemical purity in the reaction between product and appraiser. Do not accept for review a book you are predisposed to dislike, or committed by friendship to like. Do not imagine yourself a caretaker of any tradition, an enforcer of any party standards, a warrior in any ideological battle, a corrections officer of any kind. … Review the book, not the reputation.

I write reviews on this blog. Have I followed Updike’s commandments? Most are familiar to me in a hazy internalized way, even if I’ve not formalized book reviewing rules of my own. I confess guilt to giving away the ending of at least one book (a mystery novel, no less). And I could probably do better in my reviews with quoting the source material.

We live in a time of constant media negotiation. We’re not consumeristic readers any longer. With the Internet we’ve all become critics. Film review sites allows moviegoers to pan movies, even pan them before they’re released. We’re saturated with media and we’re saturated with criticism too. Updike’s rules may serve a newfound purpose: A way for us to judge criticism rather than accept it uncritically.

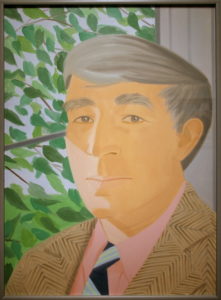

No one has ever commanded the English language like John Updike. There have been more prolific writers. Centuries earlier, there lived a writer whose light still hasn’t suffered even a partial eclipse. But no can match Updike’s style and, since that great light of centuries earlier, perhaps his cogency.

Sure, he was obsessed with certain themes and was often criticized for his “purple prose”—which seemed a bit like criticizing the sun for its heat. Perhaps it’s fair to say that Updike wasn’t a great story teller. He was a writer. And he was truly inimitable.

That much was clear when, among other things in “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu” (The New Yorker, 1960), he described Ted Williams as a “feather in a vortex”. He is more famous for his series of Rabbit novels, but Updike’s melding of tenses in The Coup is splendid. It’s something that definitely shouldn’t be attempted by less than an expert, which Hemingway would remind us does not exist in the field of writing, and it requires a bit of effort by the reader—effort far exceeded by the reward.

Updike certainly had the tools to shred anything he critiqued, but he once stated he would write ads for deodorants or labels for catsup bottles, if necessary. Many of his quotations reflect his dedication and the tremendous care with which he chose each word. He surely felt respect for those who went at “it alone” and put themselves out there as he did each time he fed that “…addiction, illusory release…” in the breezy mornings he preferred.

“Being a great writer is not the same as writing great.”

― John Updike

“I remember one English teacher in the eighth grade, Florence Schrack, whose husband also taught at the high school. I thought what she said made sense, and she parsed sentences on the blackboard and gave me, I’d like to think, some sense of English grammar and that there is a grammar, that those commas serve a purpose and that a sentence has a logic, that you can break it down. I’ve tried not to forget those lessons, and to treat the English language with respect as a kind of intricate tool.”

― John Updike

“John Updike’s genius is best excited by the lyric possibilities of tragic events that, failing to justify themselves as tragedy, turn unaccountably into comedies.”

Joyce Carol Oates, in John Updike : A Collection of Critical Essays (1979) by David Thorburn and Howard Eiland, p. 53

“Updike, I think, has never had an unpublished thought. And … he’s got an ability to put it in very lapidary prose. But … there’s eighty percent absolute dreck, and twenty percent priceless stuff. And you just have to wade through so much purple gorgeous empty writing to get to anything that’s got any kind of heartbeat in it.”

David Foster Wallace, as quoted in Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself : A Road Trip With David Foster Wallace (2010) by David Lipsky, pp. 92–93

“I can’t stand him. Nobody will think to ask because I’m supposedly jealous; but I out-sell him. I’m more popular than he is, and I don’t take him very seriously … He goes grumbling away on those born with silver spoons in their mouths— oh, he comes on like the worker’s son, like a modern-day D.H. Lawrence, but he’s just another boring little middle-class boy hustling his way to the top if he can do it.”

Gore Vidal, Comment on the UK radio show Front Row (23 May 2008)