Recently at San Francisco’s Green Apple bookstore I discovered an edition of Inward Journey (1984), a collection of essays, poetry, and remembrances dedicated to mystery writer Ross Macdonald and published shortly after his death. The collection is edited by Santa Barbara rare book seller Ralph B. Sipper, who also collaborated with Macdonald on his autobiographical Self Portrait: Ceaselessly Into the Past.

Ross Macdonald obviously affected and influenced a great number of people in and around the Santa Barbara writing scene. The anecdotes and memories related by his friends and acquaintances paint a picture of a private and thoughtful novelist who quietly guided a number of writers toward improving their craft. It’s a touching book that mostly avoids miring itself in the maudlin. Some of the writers are quite close to the subject, such as his wife’s warm and elegant recounting of an early and late memory of him. Other essayists are more distant and matter-of-fact, such as popular writer John D. MacDonald’s humorous tale of his dance with Ross Macdonald over the appropriate use of their last names in publication credits.

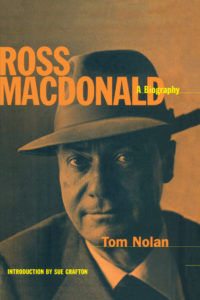

That confusion is due to Ross Macdonald being the pen name of Kenneth Millar, who adopted the name to avoid being confused with wife Margaret Millar, a well-known novelist in her own right by the time his star began to rise. On top of his feud with John D. Macdonald, he also witnessed his style of detective fiction (and his detective, Lew Archer) relentlessly compared to hardboiled writers Raymond Chandler’s and Dashiell Hammett’s work from a quarter century earlier—often to his own detriment.

Between Margaret writing under his family name, authors John D. MacDonald and Philip MacDonald, and the unasked-for competition with Chandler and Hammett, it’s a wonder Ross Macdonald was able to carve out a name for himself. He did, and his workmanlike approach to novel-writing led to a corpus of nearly thirty solid books, the bulk set in Macdonald’s own Southern California, in particular his home of Santa Barbara (renamed to Santa Teresa). As such, Macdonald inherited not merely Chandler’s mantle of the premier tough-guy detective writer, but also the mantle of the leading Southern California mystery writer. The difference is, where Chandler’s stomping grounds are Los Angeles proper, Macdonald’s Lew Archer prowls the Southern California suburbs. This shift corresponded neatly with the rapid postwar growth of the Southern California valleys and coastal communities.

Free and joyful creation

Inward Journey opens with two previously unpublished essays by Macdonald himself. “The Scene of the Crime” is a lecture he gave at the University of Michigan in 1954 regarding the origins and development of the mystery story. It’s one of the most erudite, learned, and humble essays I’ve read on the subject. Macdonald had a degree in literature (his thesis analyzed Coleridge’s Rime of the Ancient Mariner) and he draws on sources as wide-ranging as William Carlos Williams and Faulkner in way of framing the detective story as a modern narrative strategy devised in reaction to modernity itself:

“A Rose for Emily,” [Faulkner’s] most frequently reprinted story is a beautifully worked out mystery solved in a final sentence which no one who has read it will ever forget. … I don’t mean to try to borrow Faulkner’s authority in support of any such theses as these: that the mystery form is the gateway to literary grace…Still the fact remains he did use it, that the narrative techniques of the popular mystery are closely woven into the texture of much of his work.

The other chapter, “Farewell, Chandler,” originated as a private letter to his publisher Alfred A. Knopf. Pocket Books was republishing his detective novels and sought permission to “fix” them by making them more violent and sensational (and therefore more palatable to paperback readers). Macdonald was compared to Chandler his entire career, and this letter both acknowledges the debt while gingerly disentangling himself from Chandler’s legacy:

My hero is sexually diffident, ill-paid, and not very sure of himself. Compared with Chandler’s brilliant phantasmagoria this world is pale, I agree. But what is the point of comparison? This is not Chandler’s book. … None of my scenes have ever been written before, and some of them have real depth and moral excitement. I venture to say that none of my characters are familiar; they are freshly conceived from a point of view that rejects black and white classification…

A writer has to defend his feeling of free and joyful creation, illusory as it may be, and his sense that what he is writing is his own work. [emphasis mine]

These two chapters are worth reading (and worth republishing, if they’re not already.) If you’re a writer of any stripe, I would then encourage you read beyond them. Although many of the remembrances in Inward Journey are strictly personal anecdotes, more than a few dig into Macdonald’s bibliography for clues to understanding the man himself. They also relate tidbits of Macdonald’s writing habits and personal theories on fiction and form.

In particular, George Sims offers a wonderful history, book-by-book, of Macdonald’s bibliography, with highlights of his best work. The final chapters by Gilbert Sorrentino and Eudora Welty describe the evolution of Macdonald the writer (and Lew Archer, the hero) from Macdonald’s earliest works to his last. In 1954’s “The Scene of the Crime” Macdonald claims the mystery novel stands to be viewed in the same light as Zola’s and Norris’ Naturalism; Welty picks up that theme in 1984 and asserts Macdonald has earned the right to be included in the said light:

Character, rather than deed itself, is what remains uppermost and decisive to Macdonald as a novelist. In the course of its being explained, guilt is seldom seen as flat-out; it is disclosed in the round, and the light and shadings of character define its true features. … His detective speaks to us not as a moralist but as a fellow sufferer.

If you have any interest in Ross Macdonald or mystery/detective fiction, and your local library stocks this book, it’s well worth a trip to your nearest branch to absorb these chapters. It’s also available online at the Internet Archive.