When I was a teen and enamored with Dungeons & Dragons, one treasure I discovered poring over the rules books was Appendix N of the Dungeon Masters Guide. D&D co-creator Gary Gygax lists nearly thirty pulp and genre writers as major influences on the development of the game. “Upon such a base I built my interest in fantasy,” Gygax wrote, “being an avid reader of all science fiction and fantasy literature since 1950.”

In the early 1970s, Gygax and Dave Arneson harvested genre and pulp fiction to invent a new game, one that felt oddly familiar yet unlike any other experience. If “a book is a pocket or portable dreamweaver,” then Gygax and Arneson systematized that dream with charts and rules and catalogs. They took the dream off the paperback page and put it on the tabletop where it can be shared and shaped by a group of people.

If you’re familiar with D&D, most of the authors listed in Gygax’s Appendix N are unsurprising: R. E. Howard (creator of Conan), H. P. Lovecraft, Fritz Leiber (whom I’ve written about before), Michael Moorcock, J. R. R. Tolkien. Some names do surprise though, such as Leigh Brackett, whose screenwriting credits include the film noir The Big Sleep and John Wayne’s Rio Bravo. (Gygax probably included her for her planetary romances set on Mars, however.) Others would have faded into obscurity if not for Gygax’s list.

I don’t recall Appendix N being discussed much by D&D players back in the day. Decades later, the D&D blog Grognardia revealed to me that Appendix N has taken on a life of its own within the community. Gygax’s list has been studied, dissected, and emulated. There’s even an Appendix N Book Club. Blogger James Maliszewski called Appendix N the “literary DNA” of D&D.

And while Appendix N names only 20th-century authors, skimming the various rule books reveals D&D’s literary DNA also includes (in no particular order):

- Scandinavian, Teutonic, and Anglo-Saxon mythology

- Catholic demonology

- Biblical imagery

- Chivalric codes and Japanese bushido

- Fairy tales, the Brothers Grimm

- Jewish Kabbalah

- Greek mythology

- Persian, Arabic, and Islamic folklore

- Ancient mythology of Mesopotamia (Tiamat, the iconic five-headed dragon of D&D, derives from Babylonian religion)

- Hindu legends

- Arthurian tales (“Matter of Britain”)

- Western European legend, from Charlemagne to the Renaissance (“Matter of France”)

- Celtic and Irish folklore

- Slavic folklore

- Haitian folklore (although D&D’s zombies are more like 1968’s Night of the Living Dead)

- Ancient Egypt (although D&D’s mummies owe more to 1932’s The Mummy with Boris Karloff)

- Western classic literature (Frankenstein, Paradise Lost, Canterbury Tales, and more)

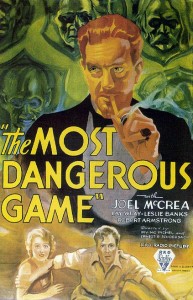

- 20th-century genres beyond those listed in Appendix N (horror and science-fiction as well as fantasy, in print and film)

This list is incomplete, but already its breadth is wild. How could a game culled from this haggis hang together in a coherent fashion, let alone grow into a cultural phenomenon played and studied fifty years later? D&D’s pulp fantasy roots help, but some credit must be chalked up to its origins in the gonzo anything-goes 1970s. Another reason is that D&D, like the written word, takes place in the mind rather than on a screen, and so inconsistencies can be papered over by the imagination and a willing suspension of disbelief.

D&D is a cultural mutt, perhaps the ultimate postmodernist pastiche. (As Jeff Rients put it: “You play Conan, I play Gandalf. We team up to fight Dracula.”) As with other collaborative games such as Exquisite Corpse, a session of D&D is never truly finished or closed. The difference is, D&D’s rules and system are open-ended. The game organizer is free to mix-and-match their own inspirations—Gygax and Arneson baked a kind of implied amendment system into their Constitution. “From such sources, as well as any other imaginative writing or screenplay you will be able to pluck kernels from which to grow the fruits of exciting campaigns,” Gygax wrote in Appendix N.

Han Solo and the Millennium Falcon crash-land in the D&D world and need the players’ help? That’ll work. A zombie apocalypse sweeping across a country village? That’ll work. Modern superheroes transported to the age of D&D? That’ll work. Referees can add their own pulpy sources and influences and, somehow, it still holds together.

There were complaints that this melange was ahistorical, especially from players who’d got it in their head D&D was to be a simulation of some sort. At its most basic, the game felt like swords and magic in Ye Olde Merrie England or thereabouts. So why do players fight Jewish golems and Egyptian mummies? Concerted efforts were made to correct Gygax’s “mistakes” and produce more historically-accurate role-playing games, such as Chivalry & Sorcery and Fantasy Wargaming. Those titles drifted into obscurity while D&D’s popularity intensified. Gygax’s and Arneson’s reception to inspiration from all sources—their “lightning rod”—was a feature, not a bug.

Not only does Appendix N indicate how widely-read Gygax and Arneson were, it also suggests how widely-read they expected the players to be. D&D wasn’t merely made by smart people, it was made for smart people.

Gygax could have used Appendix N to recommend movies, TV shows, or comic books, but chose not to. “I would never add other media forms to a reading list,” Gygax wrote in 2007, a year before his death. “If someone is interested in comic books and/or graphic novels, they’re on their own.” For me, this quote seals just how highly Gygax regarded the written word.

This post was adapted for Internet Archive’s blog: “The Fantasy Books that Inspired Dungeons & Dragons”