What if I told you that there’s been a sea-change in American storytelling over the past half-century? Not merely a change in subject matter, but that the fundamental nature of American narratives radically shifted? Would you believe me?

Now, what if I told you that a writer twenty-five years ago described these “new” stories, and even predicted they would become the dominant mode in our future? Would you believe that?

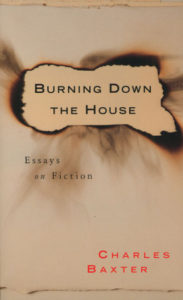

In 1997, Charles Baxter published Burning Down the House, a collection of essays on the state of American literature. It opens with “Dysfunctional Narratives: or, ‘Mistakes were Made,’” a blistering piece of criticism that not only detailed the kinds of stories he was reading back then, but predicted the types of stories we read and tell each other today.

Baxter appropriated the term “dysfunctional narrative” from poet C. K. Williams, but he expounded and expanded upon it so much, it’s fair to say he’s made the term his own. He borrowed a working definition of dysfunctional narratives from poet Marilynne Robinson, who described this modern mode of writing as a “mean little myth:”

One is born and in passage through childhood suffers some grave harm. Subsequent good fortune is meaningless because of the injury, while subsequent misfortune is highly significant as the consequence of this injury. The work of one’s life is to discover and name the harm one has suffered.

Baxter adds that the source of this injury “can never be expunged.” As for the ultimate meaning of these stories: “The injury is the meaning.”

To claim this mode of writing has become the dominant one in American culture demands proof, or at least some supporting evidence. Baxter lists examples, such as Richard Nixon’s passive-voice gloss over the Watergate cover-up (“mistakes were made”), Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres, and conspiracy theories, among others.

“Dysfunctional Narratives” doesn’t succeed by tallying a score, however. Rather, it describes a type of story that sounds all-too-familiar to modern ears:

Reading begins to be understood as a form of personal therapy or political action. In such an atmosphere, already moralized stories are more comforting than stories in which characters are making complex or unwitting mistakes.

Don’t merely consider Baxter’s descriptions in terms of books. News stories, the social media posts scrolling up your feed, even the way your best friend describes how their boss has slighted them—all constitute narratives, small or large. Dysfunctional narratives read as if the storyteller’s thumb is heavy on the moral scale—they feel rigged.

It does seem curious that in contemporary America—a place of considerable good fortune and privilege—one of the most favored narrative modes from high to low has to do with disavowals, passivity, and the disarmed protagonist.

(I could go one quoting Baxter’s essay—he’s a quotable essayist—but you should go out and read all of Burning Down the House instead. It’s that good.)

Dysfunctional narratives are a literature of avoidance, a strategic weaving of talking points and selective omission to harden their messaging and block counter-criticism. If that sounds like so much political maneuvering, that’s because it is.

“Mistakes were made”

Let’s start with what dysfunctional narratives are not: They’re not merely stories about dysfunction, as in dysfunctional families, or learning dysfunctions. Yes, a dysfunctional narrative may feature such topics, but that is not what makes it dysfunctional. It describes how the story is told, the strategies and choices the author had made to tell their story.

Baxter points to Richard Nixon’s “mistakes were made” as the kernel for the dysfunctional narrative in modern America. (He calls Nixon “the spiritual godfather of the contemporary disavowal movement.”). He also holds up conspiracy theories as prototypes:

No one really knows who’s responsible for [the JFK assassination]. One of the signs of a dysfunctional narrative is that we cannot leave it behind, and we cannot put it to rest, because it does not, finally, give us the explanations we need to enclose it. We don’t know who the agent of action is. We don’t even know why it was done.

Recall the tagline for The X-Files, a show about the investigation of conspiracy theories: “The truth is out there.” In other words, the show’s stories can’t provide the truth—it’s elsewhere.

More memorably—and more controversially—Baxter also turns his gaze upon Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres, which features the use of recovered memories (“not so much out of Zola as Geraldo“) and veers into “an account of conspiracy and memory, sorrow and depression, in which several of the major characters are acting out rather than acting, and doing their best to find someone to blame.”

In a similar vein, a nearly-dysfunctional story would be The Prince of Tides by Pat Conroy. It involves a family man who, via therapy, digs through memories of a childhood trauma which has paralyzed him emotionally as an adult. He gradually heals, and goes on to repair his relationship with his family. Notably, his elderly father does not remember abusing him years earlier, leaving one wound unhealed.

Another example would be Nathanael West‘s A Cool Million, which follows a clueless naif on a cross-American journey as he’s swindled, robbed, mugged, and framed. By the end, the inventory of body parts he’s lost is like counting the change in your pocket. It might be forgiven as a satire of the American dream, but A Cool Million remains a heavy-handed tale.

This leads to another point: A dysfunctional narrative is not necessarily a poorly told one. The dysfunction is not in the quality of the telling, but something more innate.

Examples of more topical dysfunctional narratives could be the story of Aziz Ansari’s first-date accuser. The complaints of just about any politician or pundit who claims they’ve been victimized or deplatformed by their opponents is dysfunctional. In almost every case, the stories feature a faultless, passive protagonist being traumatized by the more powerful or the abstract.

There’s one more point about dysfunctional narratives worth making: The problem is not that dysfunctional narratives exist. The problem is the sheer volume of them in our culture, the sense that we’re being flooded—overwhelmed, even—by their numbers. That’s what seems to concern Baxter. It certainly concerns me.

A literature of avoidance

In his essay Ur-Fascism, Umberto Eco offers this diagram:

| one | two | three | four |

| abc | bcd | cde | def |

Each column represents a political group or ideology, all distinct, yet possessing many common traits. (Think of different flavors of Communism, or various factions within a political party.) Groups one and two have traits b and c in common, groups two and four have trait d in common, and so on.

Eco points out that “owing to the uninterrupted series of decreasing similarities between one and four, there remains, by a sort of illusory transitivity, a family resemblance between four and one,” even though they do not share any traits. The traits form a chain—there is a common “smell” between the political groups.

Not all dysfunctional narratives are exactly alike, or have the exact traits as the rest, but they do have a common “smell.” Even if a 9/11 conspiracy theory seems utterly unlike A Cool Million, they both may be dysfunctional.

Likewise, in the traits that follow, just because a story doesn’t include all doesn’t mean it “avoids dysfunction.” Rather, dysfunctional narratives are built by the storyteller selecting the bricks they need to buttress their message:

- A disarmed protagonist

- An absent antagonist

- Minimal secondary characters

- An authorial thumb on the scale

- “Pre-moralized”

- A vaporous conclusion

- Authorial infallibility and restricted interpretations

The most common trait of the dysfunctional narrative is a faultless, passive main character. Baxter calls this the “disarmed protagonist.” Baxter differentiates between “I” stories (“the protagonist makes certain decisions and takes some responsibility for them”) and “me” stories (“the protagonists…are central characters to whom things happen”). Dysfunctional narratives are the “me” stories.

And the errors these “me” characters make—if any—are forgivable, understanding, or forced upon them by dire circumstances. Compare this to the mistakes the people around them make—monstrous, unpardonable sins:

…characters [in stories] are not often permitted to make interesting and intelligent mistakes and then to acknowledge them. The whole idea of the “intelligent mistake,” the importance of the mistake made on impulse, has gone out the window. Or, if fictional characters do make such mistakes, they’re judged immediately and without appeal.

Power dynamics are a cornerstone of all narratives, but one “smell” of the dysfunctional variety is an extraordinary tilting of power against the main character. The system, or even the world, is allied against the protagonist. Close reads of these narratives reveals an authorial thumb on the story’s moral scale, an intuition that the situation has been soured a bit too much in the service of making a point. This scale-tipping may be achieved many ways, but often it requires a surgical omission of detail.

Hence how often in dysfunctional narratives the antagonist is absent. A crime in a dysfunctional novel doesn’t require a criminal. All it needs, in Robinson’s words, is for the main character to have endured some great wrong: “The work of one’s life is to discover and name the harm one has suffered.”

Name the harm, not the perpetrator. Why not the perpetrator? Because often there’s no person to name. The harm is a trauma or a memory. The perpetrator may have disappeared long ago, or died, or have utterly forgotten the wrongs they inflicted (as the father does in Prince of Tides). The malefactor may be an abstraction, like capitalism or sexism. But naming an abstraction as the villain does not name anything. It’s like naming narcissism as the cause of an airliner crash. This is by design. Abstractions and missing antagonists don’t have a voice; even Satan gets to plead his case in Paradise Lost.

No ending is reached in a dysfunctional narrative, because there’s only a trauma, or a memory, or an abstraction to work against. These injuries never heal. Memories may fade, but the past is concrete. By telling the story, the trauma is now recorded and notarized like a deed. “There’s the typical story in which no one is responsible for anything,” Baxter complained in 2012. “Shit happens, that’s all. It’s all about fate, or something. I hate stories like that.” These stories trail off at the end, employing imagery like setting suns or echoes fading off to signify a story that will never conclude.

The most surface criticism of these narratives is that we, the readers, sense we’re being talked down to by the author. “In the absence of any clear moral vision, we get moralizing instead,” Baxter writes. A dysfunctional narrative dog-whistles its morality, and those who cannot decode the whistle are faulted for it. The stories are pre-moralized: The reader is expected to understand beforehand the entirety of the story’s moral universe. For a reader to admit otherwise, or to argue an alternate interpretation, is to risk personal embarrassment or confrontation from those who will not brook dissent.

And making the reader uncomfortable is often the outright goal of the dysfunctional narrative. The writer is the presumed authority; the reader, the presumed student. It’s a retrograde posture, a nagging echo from a lesser-democratic time. (When I read A Brief History of Time, I was most certainly the student—but Hawking admirably never made me feel that way.) Dysfunctional narratives are often combative with the reader; they do not acknowledge the reader’s right to negotiate or question the message. With dysfunctional narratives, it’s difficult to discern if the writer is telling a story or digging a moat around their main character.

“What we have instead is not exactly drama and not exactly therapy,” Baxter writes. “No one is in a position to judge.” A dysfunctional narrative portrays a world with few to no alternatives. A functional narrative explores alternatives. (This is what I mean when I write of fiction as an experiment.)

This is why so many dysfunctional narratives are aligned to the writer’s biography—who can claim to be a better authority on your life, after all? But the moment a reader reads a story, its protagonist is no longer the author’s sole property. The character is now a shared construct. Their decisions may be questioned (hence the passive nature of the protagonists—inaction avoids such judgements.) If the author introduces secondary characters, they can’t claim similar authority over them—every additional character is one more attack vector of criticism, a chipping away of absolute authority over the story itself. That’s what happened to sensitivity reader Kosoko Jackson in 2019, whose debut novel was pulped due to questions over his secondary characters.

Of all the traits listed—from the disarmed protagonist to the vaporous conclusion—the trait I find the “smelliest” is authorial infallibility and restricted interpretation. That’s why I used weasel language when I called Prince of Tides “nearly-dysfunctional:” The book is most certainly open to interpretation and questioning. In contrast, questioning a conspiracy theory could get you labeled an unwitting dupe, a useful idiot, or worse.

A Cambrian explosion

What Baxter doesn’t explore fully is why we’ve had this Cambrian explosion of dysfunctional narratives. He speculates a couple of possibilities, such as them coming down to us from our political leadership (like Moses carrying down the stone tablets), or as the byproduct of consumerism. I find myself at my most skeptical when his essay stumbles down these side roads.

When Baxter claims these stories arose out of “groups in our time [feeling] confused or powerless…in such a consumerist climate, the perplexed and unhappy don’t know what their lives are telling them,” it seems Baxter is offering a dysfunctional narrative to explain the existence of dysfunctional narratives. He claims they’re produced by people of “irregular employment and mounting debts.” I strongly doubt this as well. In my experience, this type of folk are not the dominant producers of such narratives. Rather, these are the people who turn to stories for escape and uplift…the very comforts dysfunctional narratives cannot provide, and are not intended to provide.

Rather than point the finger at dead presidents or capitalism, I’m more inclined to ascribe the shift to a handful of changes in our culture.

The term “The Program Era” comes from a book by the same name detailing the postwar rise and influence of creative writing programs in the United States. This democratization of creative writing programs was not as democratic as once hoped, but it still led to a sharp increase in the numbers of people writing fiction. Most of those students were drawn from America’s upper classes. And, as part of the workshop method used in these programs, it also led to a rise in those people having to sit quietly and listen to their peers criticize their stories, sometimes demolishing them. (Charles Baxter was a creative writing professor and the head of a prominent writing program in the Midwest. Many of his examples in Burning Down the House come from manuscripts he read as an instructor.)

With the expansion of writing programs came a rise in aspiring writers scratching around for powerful subject matter. Topics like trauma and abuse are magnets when seeking supercharged dramatic stakes. Naturally, these writers also drew from personal biography for easy access to subject matter.

Another reason is staring back at you: The World Wide Web has empowered the masses to tell their stories to a global audience. This has created a dynamic where everyone can be a reader, a writer, and a critic, and all at the same time.

The natural next step in the evolution of the above is for storytellers to strategize how best to defend their work—to remove any fault in the story’s armor, to buttress it with rearguards and fortifications. And there’s been a shift in why we tell stories: Not necessarily to entertain or enrich, but as an act of therapy or grievance, or to collect “allies” in a political climate where you’re either with me or against me.

Pick up a university literary magazine and read it from cover to cover. The “smell” of dysfunctional narratives is awfully similar to the smell of social media jeremiads.

These are not the kind of stories I want to read, but it’s becoming increasingly difficult to distance myself from them. Writers should strive to offer more than a list grievances, or perform acts of score-settling. If it’s too much to ask stories to explain, then certainly we can expect them to connect dots. Even if the main character does not grow by the last page, we should grow by then, if only a little.

The Tusk has posted a new piece of mine about the tortured history of my new novel

The Tusk has posted a new piece of mine about the tortured history of my new novel