Previously: The Shoot Horses, Don’t They?

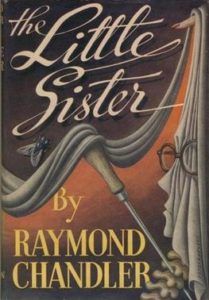

With Raymond Chandler so intimately associated with mid-century Los Angeles, and Chandler so determined to record the city’s excesses through his gimlet eye, it’s surprising how little of Hollywood makes it into his detective novels. The only one to dwell on the movie trade is The Little Sister, and even then, it takes twelve chapters until the reader learns the plot is somehow connected to Hollywood. Yet, The Little Sister is often nominated as one of the greatest Hollywood novels ever made.

By the time The Little Sister was published in 1949, Chandler had built a name in Hollywood as a successful screenwriter. His Oscar-nominated script for the landmark Double Indemnity (co-written with director Billy Wilder) was lauded as both an honest adaptation of James M. Cain’s bestseller and, incredibly, an improvement on the source material, which had been declared a modern classic soon after publication. Chandler was also called in to rewrite dialogue on other films, as his brisk, wisecracking style was in high demand.

Compare Chandler’s entry to Hollywood to Nathanael West’s, who churned out unremarkable scripts while writing The Day of the Locust. West did not travel to Los Angeles with stars in his eyes, nor did he arrive with impressive credentials. He strove to become a serious novelist, not a screenwriter of cheap Westerns and jungle adventures. It was the Great Depression, though, and he heard that Hollywood paid good money for writing.

He heard more than that, actually. According to Marion Meade’s Lonelyhearts, it was West’s brother-in-law—New Yorker writer S. J. Perelman—and his frothing disgust with Hollywood (“where holding a job was ‘a series of hysterical genuflexions and convulsive ass-kissings'”) that lured West to Los Angeles in search of foul-mouthed grotesqueries and high-glamour oddities he could transfer to the page. It’s not difficult to imagine Nathanael West as a character in a Raymond Chandler mystery…if only there was a blackmail angle.

As Chandler tiptoed through Hollywood’s land mines and manure fields, writing screenplays, dialogue, and movie treatments, he discovered he was not revolted or disgusted with what he saw. He was bored.

“An industry with such vast resources and such magic techniques should not become dull so soon,” he wrote in The Atlantic in 1945. “Hollywood is a showman’s paradise. But showmen make nothing; they exploit what someone else has made.”

One fascinating vein running through my list of great Hollywood novels is how often the authors were involved in the business—not only were they witnesses, they were collaborators in the insanity they documented.

“Hollywood is easy to hate,” Chandler wrote in The Atlantic, “easy to sneer at, easy to lampoon. Some of the best lampooning has been done by people who have never been through a studio gate.” By the time he wrote The Little Sister, though, he’d been through the studio gate many times.

Like Ross MacDonald, Chandler realized early on he could leverage the American hard-boiled detective novel to write about America grappling with modernity, a country suddenly flush with money and influence. The detective novel is told from the perspective of an outsider with a keen grasp of social, political, and economic realities. Chandler went heavy on the grotesque when he depicted Los Angeles, populating his novels with fortune tellers for the rich, perfumed gigolos, mob toughs talking like they had been borrowed from Hemingway’s “The Killers,” and so forth.

Chandler reels it in for The Little Sister. The novel is a bit drier than his earlier work. Most Hollywood novels brim with a fatalistic cynicism, but Chandler incorporated a more literal, perhaps even-handed, depiction of Tinseltown.

This literal-mindedness is what prevents The Little Sister from falling into a trope of American writing, the moralizing take-down of Hollywood as a depraved and greedy trade. Re-reading the novel for this post, I noted Chandler had included some basic scenes missing from the others in this list. His detective, Philip Marlowe, visits a sound stage during filming, where he witnesses a catty back-and-forth between the actors after the scene is flubbed. Afterwards, he drops in on a rising starlet in her dressing room. Another chapter is devoted to dealing with a big-shot movie agent eager to protect his client. These business-like scenes are the building blocks of the second half of The Little Sister.

In 1944, Chandler wrote to Atlantic editor Charles Morton:

Hollywood is the only industry in the world that pays its workers the kind of money only capitalists and big executives make in other industries. … Its pictures cost too much and therefore must be safe and bring in big returns; but why do they cost too much? Because it pays the people who do the work, not the people who cut coupons.

Marlowe sinks into this moneyed and territorial industry as ably as he deals with alcoholic flophouse managers and gangsters who dabble with ice-picks to the neck. Marlowe is surefooted no matter the situation. He is a man of all people, but party to none. This is the character type Chandler honed to a point. It was a character he used time and again to turn over rocks across Southern California to reveal the grubby crustaceans and sun-bleached bones beneath.

On the right the great fat solid Pacific trudging into shore like a scrubwoman going home. No moon, no fuss, hardly a sound of the surf. No smell. None of the harsh wild smell of the sea. A California ocean. California, the department-store state. The most of everything and the best of nothing. Here we go again. You’re not human tonight, Marlowe.

The Little Sister, ch. 13

The one notable grotesque in The Little Sister is the near-real-time transformation of a Midwestern bookish, prudish young woman into a walking caricature of a star-struck pursuer of Tinseltown sophistication. Like the climax of Locust, a critical point is reached, something snaps, and Hollywood’s vapory facade mists away to something more earthy and damning.

Chandler allows a sliver of redemptive light to shine through the smoke-filled backrooms, and it lands on the unlikeliest of characters. (“Lots of nice people work in pictures,” Marlowe notes unironically at one point.) Chandler was far more the softie than his books’ hard-boiled reputation suggests. The Little Sister ends in a surprising place: Perhaps the problem is not with Hollywood, but with those too eager to believe its illusions.